Bird’s eye view of Rashid Johnson, Within Our Gates.

Photo: Cait Munro.

It’s only been ten months since the Garage Museum for Contemporary Art opened the doors on its massive, Rem Koolhaas-designed Gorky Park location, and yet, everything from the expertly-curated gift shop to the cozy, constantly buzzing cafe feels as polished and purposeful as if it had been up and running for years.

The institution’s spring exhibition lineup, which includes Rashid Johnson’s “Within Our Gates,” Taryn Simon’s “Action Research/The Stagecraft of Power,” and Viktor Pivovarov’s “The Snail’s Trail” is no exception, bringing together three distinct perspectives with more in common than initially meets the eye.

“Garage’s spring season invites you to clear out the cobwebs of your mind—if you like, it’s spring cleaning,” said curator Kate Fowle during a press conference. “[One] theme or common thread that you’ll find is that each artist presents us with work whereby facts are much stranger than fiction.”

Rashid Johnson and Taryn Simon, installation view.

Photo: Cait Munro.

Simon’s multi-part exhibition addresses hot-button topics like governmental treaties and nuclear power mainly through two series of sleek, attractive photographs, all of which contain significantly more backstory that initially meets the eye. Simon’s is a heavily research-based practice, and in this context, her work helps bridge the gap between Johnson’s ambitious installation and Pivovarov’s highly conceptual paintings and works on paper.

Situated directly below Simon’s work, by the main entrance to the museum, is Johnson’s site-specific, sculptural installation, which he and a team of friends and helpers spent two weeks erecting.

“When he arrived at Garage, he was met with what he asked us to prepare, which was 71 metal beams, 420 plants, 175 lights, over 200 books, 1,200 pounds of shea butter, 12 carpets, and a number of other, smaller things, as well as two experts—one from the Moscow botanical garden and one from the museum,” Fowle recalled.

Rashid Johnson, Plateaus (detail), 2014

Photo: Fredrik Nilsen. Courtesy David Kordansky Gallery, Los Angeles. © Rashid Johnson.

Johnson refers to the installation, which is made up of an artful hodgepodge of plants, books, television screens, and ornate rugs situated amidst a welcoming maze of metal boxes and softly glowing lights as “a brain.” Indeed, the marriage of high and low culture (W.E.B Du Bois’s The Souls of Black Folk meets a TV blaring Rocky IV) feels simultaneously intellectual and inviting—a bit like being inside the buzzing mind of a thoughtful, hyperactive friend. And like the museum’s beloved cafe area, it’s the kind of place you just want to hang out in.

“The goal is to create a series of contradictions, and it’s not dissimilar from the contradictions that live in all of our experiences,” Johnson said during an interview. “I think an artwork that, in a sense, doesn’t focus on specifics about our experience, but allows you to be challenged with the more macro kind of concerns that so many of us have is one that, for me, becomes more successful.”

Taryn Simon, Agreement Establishing the International Islamic Trade Finance Corporation Al-Bayan Palace, Kuwait City, Kuwait, May 30, 2006

Rosa × hybrida, Hybrid Tea Rose, Ecuador, Gerbera × hybrida, Gerbera, Netherlands, Hydrangea macrophylla, Big Leaf Hydrangea, Netherlands, Dendrobium hybrid, Dendrobium, Thailand (2015).

Photo: Taryn Simon/Gagosian Gallery.

While those unfamiliar with Russian culture will find Simon and Johnson’s work more approachable, it was clear during the opening festivities that Pivovarov’s exhibition was of the most consequence for the local audience. Dubbed by one museum worker as the “Russian Shel Silverstein,” the 80-year-old artist is a seminal figure in Russia, having illustrated several popular children’s books.

While living in Moscow in the 1960s and ’70s, Pivovarov and fellow artist Ilya Kabakov pioneered the Moscow Conceptualist movement, which reveled in samizdat works. Since the government at the time effectively banned any artwork that wasn’t illustration-based, Pivovarov and his contemporaries created much of their work inside notebooks that could be both easily shared and easily concealed.

After moving to Prague in 1982, Pivovarov began to work on a larger scale, producing painting and sculpture, but was also imbued with a sense of loneliness and isolation away from his colleagues and the art scene he knew.

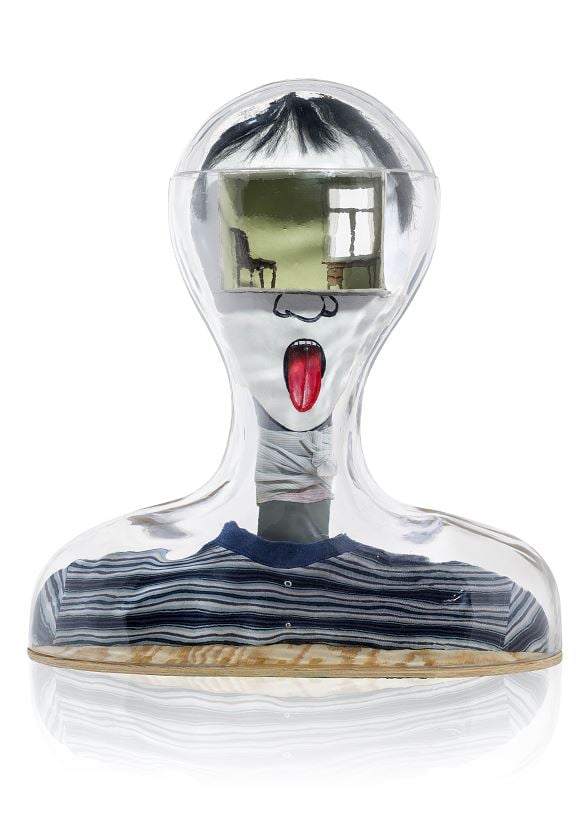

Viktor Pivovarov, Black Apple (1977).

Image: Courtesy of Dilyara Allakhverdova and Elchin Safarov.

“The Snail’s Trail” traces Pivovarov’s career across 11 rooms, each of which reveals a particular emotional experience, ranging from romantic love to horror, death, and extreme isolation. These feelings are expressed through imagery, language, and concepts that are highly familiar to a Russian audience—some even loosely reference Pivovarov’s own children’s book illustrations—but that to outsiders come across as surreal. An in-depth exhibition guide, written by the artist and translated into English, helps provide context.

“A child sees a world where the ego has not yet been separated from the id, and where subject and object are the same thing,” Pivovarov writes in reference to iconic paintings like This is Radio Moscow (1992) and The Long, Long Arm (1972), which appear in the show’s second room. “This is the paradise that will later be lost. This is also the place—the state of being one with the world—which we will always try to return to throughout our journey.”

Viktor Pivovarov, A bird reading in a landscape (after a picture by Carl Spitzweg) (1998).

Courtesy of ART4 Museum.

This notion of a journey, be it physical, mental, or spiritual, is one that’s echoed throughout the Garage’s spring exhibition series. For Simon, it’s an often physical trip through the inner workings of social structures, one in which she consistently cuts through red tape to reveal the bizarre truths of human existence. For Johnson, it’s a journey through the contents of his own heart and mind to identify the texts, films, objects, and ideas that have influenced him, and to finally create an environment through which these influences can be communicated to others. For Pivovarov, it’s a journey through his own career, and ultimately, his psyche.

For all of their differences, it’s a unique gift of these three artists, as well as the museum’s curators, to be able to condense and communicate such epic pilgrimages into something audiences can absorb.

As Pivovarov writes: “Any journey begins with a moment of wonder…As we grow older, we lose the ability to feel it.”

Viktor Pivovarov, Atlas of Animals and Plants (2015).

Image: Collection of the artist.