There’s an anecdote buried deep inside the footnotes of the catalog for the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Garry Winogrand survey that speaks volumes about the present exhibition. In it, his better known contemporary, Lee Friedlander, watches Winogrand release the shutter of his camera with nearly every passerby encountered on a New York street. Thirty years after Winogrand’s quick dispatch from cancer in 1984, Friedlander’s shocked response to his friend’s incontinence appears more informative than lapidary: “Garry, you’re not photographing, you’re taking the census.”

Instead of a picture of a camera-wielding automaton, the current retrospective at the Met—organized by the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art and the National Gallery—paints a portrait of Winogrand as a dynamic but perennially unresolved artist in some 175 images, a third of them never seen before. The Bronx-born shutterbug was, in fact, so hell-bent on capturing the country’s postwar climb to the middle—in pictures of hippies, hard hats, bare-legged girls, rodeo cowboys, and flannel-suited Rotarians—that, towards the end, he barely stopped to develop or edit his photographs. The age demanded that kind of star-spangled kamikaze spirit from some of its best artists. Not for nothing does Friedlander’s comment sync up wickedly with Truman Capote’s bitchy remark about Jack Kerouac’s On the Road: “That’s not writing, that’s typing.”

Garry Winogrand, New York (1965). Collection of Randi and Bob Fisher

© The Estate of Garry Winogrand, courtesy Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco.

Winogrand not only did not ever attempt a proper summa of his work, he avoided the subject like the plague. In life, he was partial to declarations of Whitmanesque openness—he once told the photographer Jay Maisel that he sought chiefly to describe “the chaos of life.” In death, he left an inheritance of questionable value: a third of a million unedited exposed frames of film; more than 2,500 undeveloped rolls (100,000 frames); plus a photographic legacy for friends and allies to sort out. One of his staunchest supporters was MoMA’s legendary curator of photography John Szarkowski. A Virgil for the passage of modern photography from glossy publications, like Life and Look, into fine art museums, it was this powerful frenemy who decided that Winogrand’s late photographs did not make the cut.

“To expose film is not quite to photograph,” Szarkowski said grumpily after wading through stacks of prints, contact sheets and undeveloped stock while piecing together Winogrand’s first survey. His final word about the photographer’s late pictures, taken between 1971 and 1984, was equally unenthused. Setting the tenor for three decades of received wisdom, the curator declared that Winogrand’s loosely composed, wide-angled photos of Joe and Jane Fleshpot from sun-drenched boomtowns like Dallas, Forth Worth, Los Angeles, Austin, and San Francisco, resembled “an engine that goes on firing even after it has been turned off.”

Garry Winogrand, Fort Worth (1974–77). The Garry Winogrand Archive, Center for Creative Photography, The University of Arizona © The Estate of Garry Winogrand, courtesy Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco.

Predictably, Leo Rubinfien, the guest curator of the Met’s eponomously named exhibition, “Garry Winogrand,” begs to differ. “There exists in photography no other body of work of comparable size or quality that is so editorially unresolved,” he says. Rubenfein goes on to argue in the present show that Winogrand’s less iconic pictures are very much of a piece with his more recognizable New York photographs—his comely Herald Square babes and garrulous Coney Island beach scenes, for instance.

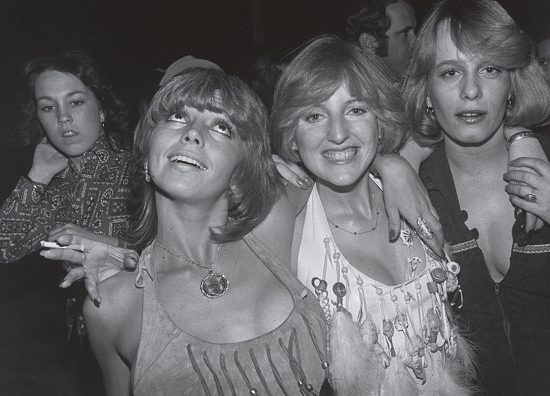

On the evidence, he has a point. Thanks to Rubinfien’s diligent efforts, “Garry Winogrand” features some 56 posthumous prints and 164 new reproductions in the exhibition catalog. Not a few of these loosely composed images bring to mind certain casual-looking contemporary photography of youth subcultures; others are weirdly expansive showstoppers. Their subject is the epic of America having reached the end of the road.

Take Winogrand’s 1983 photograph of a tranny in pancake makeup and a chiffon dress walking down a four-lane blacktop in L.A. A baffling if gripping image (Who is she? What is she doing? Is she leading a parade?), this and other posthumously printed pictures—like that of a beer-guzzling rock concert attendee and a bare-breasted stripper at L.A.’s Ivar Theatre—capture America’s weird post-utopian pageant of assertive libertinism with unprocessed brio. Rather than decisive images captured by a photographer-author like Cartier-Bresson, these pictures augur a photographic passivity not witnessed fully until Philip-Lorca DiCorcia’s “Streetwork” series a decade later.

Christopher Isherwood’s opening to his Berlin Diary comes to mind here: “I am a camera with its shutter open, quite passive, recording, not thinking.” After the turmoil of Kent State, Vietnam, Watergate, the oil crisis, and the Iran Hostage fiasco, among other age-defining debacles, Winogrand’s late creative ethos seems fitting for a social, cultural, and economic bust the collective psyche has yet to come to grips with. Like most great photographers, Winogrand took pictures primarily to find out what things looked like in photographs. His principal subject—he declared himself “a student of America”—changed radically as he matured.

Like Kerouac’s On the Road, Winogrand’s late pictures at the Met bristle with unresolved tensions. They are partly his and partly ours. It was Winogrand’s genius to have opened himself up and his camera to their possibilities.

“Gary Winogrand” is on view at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, through September 21, 2014