“Everything has been destroyed in Gaza—institutions, galleries, artifacts, historical sites, mosques, and churches,” Andre Ibrahim said in a phone interview with Artnet recently, speaking from the West Bank. “The most powerful response you can have to that is to create again.”

Ibrahim is one of the organizers of the recently announced Gaza Biennale. The initiative looks to bring together a group of artists, some working under fire amid the ongoing war in Gaza and some who have fled, supported by colleagues in the West Bank.

An installation view of work by Aya Juha in her studio in North Gaza. Photo courtesy of the Forbidden Museum

Ibrahim is affiliated with the Al Risan Art Museum, which is helping sponsor the exhibition. He explained that the Gaza Biennale initiative was originally born from conversations with Tasneem Shatat, an artist from Khan Younis in Gaza. Shatat contacted the institution in April 2024 and has since become its first resident artist.

“Tasneem said that there are all these artists in Gaza who are working,” Ibrahim recalled. “So, a network started to develop to connect artists in Gaza, which eventually led to the project. Calling it a ‘biennale’ during the early planning phase was the best way to describe what we were trying to undertake collectively. The term was debated for a bit and it sort of stuck. It has evolved from there into a real biennale with more than 50 artists.”

The organizers do not currently have any institutional partners to show the work inside Gaza. Ibrahim said participating artists are more interested in having their work reach a wider audience in Europe or the United States, and he’s leading the efforts to find the biennale a home, seeking institutional partners both at home and abroad. The initiative is raising $90,000 to fund the artists.

“It is a message to the art world that there are artists working under unbelievable circumstances, facing obstacles and the harshest conditions, and still creating work, talking about art, teaching art, and running workshops with kids,” Ibrahim said.

Aya Juha. Anas (2024). Photo courtesy of Forbidden Museum

The artists in the biennale come from all over Gaza, Ibrahim added, including from the particularly devastated region of North Gaza. “As horrible as everything is all over Gaza, North Gaza is a whole other level. These artists totally blow my mind.”

He expressed particular awe about the work of the artist Aya Juha. “She’s creating unbelievable work that’s about what happened to her and dedicated to her brother, who was martyred,” Ibrahim said. “She’s addressing issues of imprisonment, torture, and the brutality of what’s happening to the people of Gaza by telling the story of her brother through a series of paintings made in her bombed-out studio.” In fact, Juha’s partly destroyed workspace has become a gallery to exhibit her work to the people of North Gaza, Ibrahim explained.

Fatema Abu Owda. For the exhibition “The Red Feet.” (2024). Photo courtesy of the Forbidden Museum

Other participating artists such as Ahmed Muhanna are making work using very limited supplies, adapting out of necessity to the conditions in Gaza. Reached by Artnet through social media, Muhanna said he had been a specialist in art therapy for children before the war while maintaining his own artistic practice in his studio on the side.

“Since the war entered Gaza, everything was turned upside down from the feeling of fear and excessive anxiety,” he said. During the first three months of the conflict, Muhanna explained, he could not hold a pen or brush from the shock, but he has since returned to a studio overlooking the streets of Gaza.

“With the passage of time, at the beginning of 2024, I gathered my strength as if something inside me was telling me, ‘You are strong and you are an artist, you must gather yourself and send a message that you have something in this world,’” he said.

Alaa Al Shawa. From the exhibition “Fading Gestures.” (2024) Photo courtesy of the Forbidden Museum

Muhanna has created a series of works using aid boxes air-dropped or delivered into Gaza. “He started taking the boxes apart and using the pieces to tell the story of life where he is, using the box as part of the artwork,” Ibrahim explained. “He only had a few supplies, so he found charcoal from burnt sticks from a fire. If you look at the images, you think it’s someone in a studio making it, but he’s figuring out things around him to make the work.”

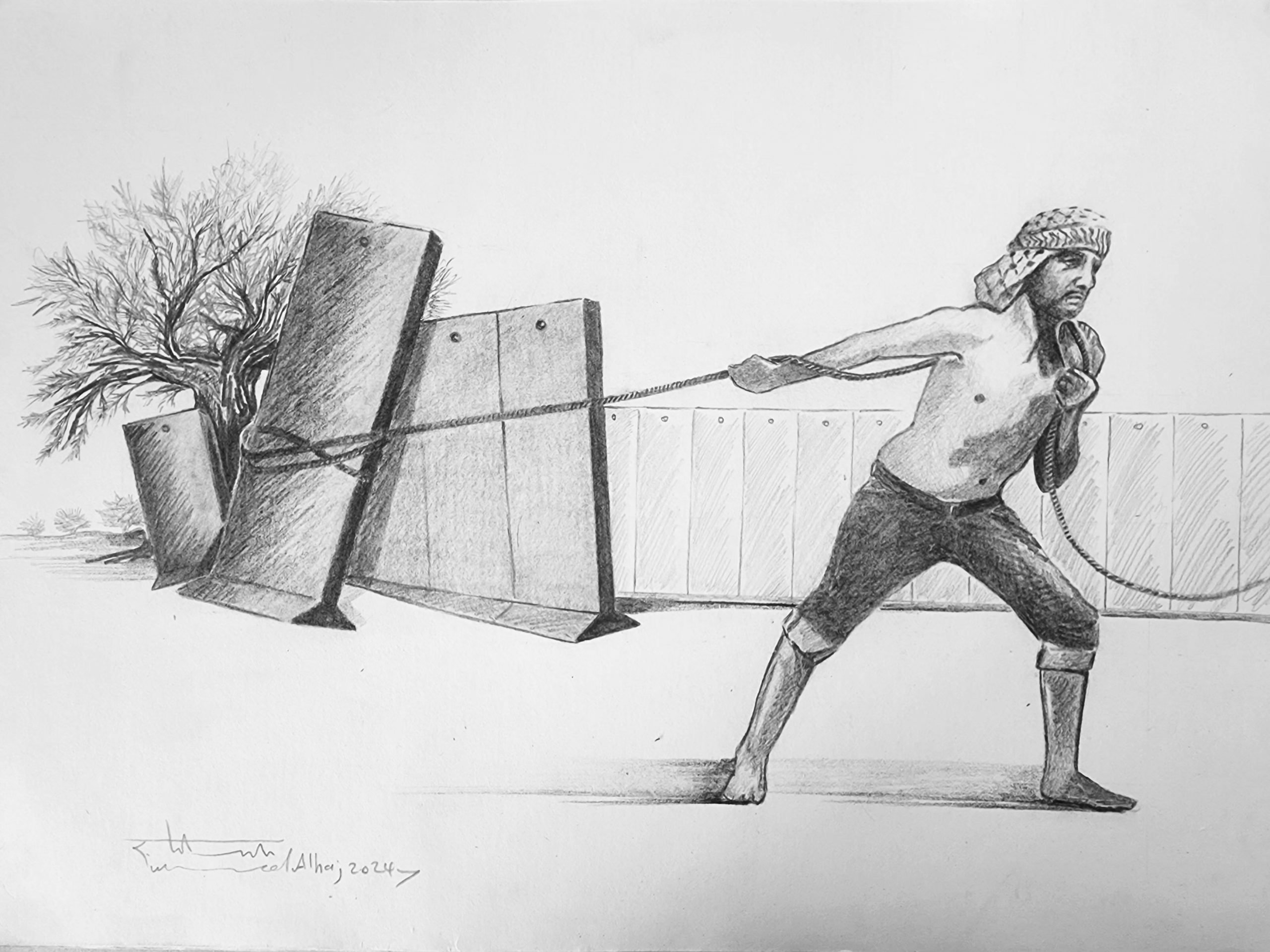

Ghanim Said Al-din, meanwhile, has found a way to make the separation of the Palestinian enclaves of the West Bank and Gaza part of his work. The artist conceptualized his artwork from his tent in Gaza. Notes and instructions for installation are fed to artists in the West Bank who collaborate in its creation by fabricating the work.

“To what extent his notes will be part of the exhibition remains to be seen, but they are quite beautiful images of his desk where he’s working and what he’s constructing,” Ibrahim said. “It’s a very interesting project which is his way of bringing politics into everyday life.”

Meanwhile, Malaka Abu Owda is creating work using a tablet computer in the town of Al-Mawasi in the Rafah region of Gaza. Ibrahim commended her for making digital work in a way that it is still “very textured.” Her mother, Fatema Abu Owda, is also an artist, though one who prefers to work with physical media and even creates her own colors for her vivid artworks.

Yasmeen Al Daya. Embrace (2024). Photo courtesy of the Forbidden Museum

“Fatema is an incredible woman and artist,” Ibrahim said. “She has been doing these beautiful workshops for kids for free. They are displaced in a tent. She also has very limited supplies. So she started making colors for her paintings, red maybe from some spice or something.”

Like Malaka, the artist Osama Naqqa is making black-and-white drawings digitally from his phone in the Khan Younis region of Gaza. “It’s unbelievable, the detail and the power he’s creating on his phone with his finger,” Ibrahim said.

Not all the artists participating in the Gaza Biennale are still in Gaza. Some have been able to leave and are now in Egypt, Europe, or elsewhere. One of these is Hala Eid Al-Naji, a young female artist now in Cairo.

People are seen participating in the interactive exhibit “Nazah’s Lexicon” from Palestinian artist Hala Eid Al-Naji, currently on display in Cairo and part of the planned Gaza Biennale. Photo courtesy of Hala Eid Al-Naji

Al-Naji has created a project called Nazeh’s Lexicon, a single large installation with multiple parts that the artist described to Artnet as an “immersive journey” showing the displacement of Palestinians from their homeland in Gaza. The installation is currently mounted as a solo show at Kodak Courtyard in Cairo. The work is inspired by a character named “Nazeh” created by her colleague Mohammed Alhaj, who is separately a participant in the Gaza Biennale.

“Although it is a solo exhibition, I consider it the culmination of a collective effort,” Al-Naji said. “Launching this work amidst an ongoing genocidal war was no easy task. The idea began as a modest gathering of displaced artists and architects from Gaza who had relocated to Egypt. It started with us recounting the painful narratives of displacement.”

As this group of artists talked, she noticed that the stories were filled with “rich linguistic expressions” that uniquely describe the situation in Gaza and the subsequent experience of exile. The installation “showcases a collection of terms, expressions, and colloquial words that capture the manifestations of daily life during displacement,” she said.

A person is seen viewing an art installation by Palestinian artist Hala Eid Al-Naji, currently on view in Cairo. It is part of the planned Gaza Biennale. Photo courtesy of Hala Eid Al-Naji

At the heart of Nazeh’s Lexicon is an interactive map of the Gaza Strip with stories “etched into its wooden surface.” The oral histories of Palestinians being passed on through storytelling often “feel inadequate.” As a consequence, she said, “a stronger, more respectful medium was needed—one that honors their pain and wounds.”

Displaced Palestinians from Gaza are invited to participate in the interactive installation and trace their own displacement journeys, she said.

“We are doing this to stop the war,” Ibrahim said. “It is in the hands of Western and Arab governments to stop this war, we all know that. Our message to them, to their institutions, is that we are over 50 artists telling the world that Palestine is still alive and Palestinians in Gaza are not victims but our guides to lead us out of this crisis.”