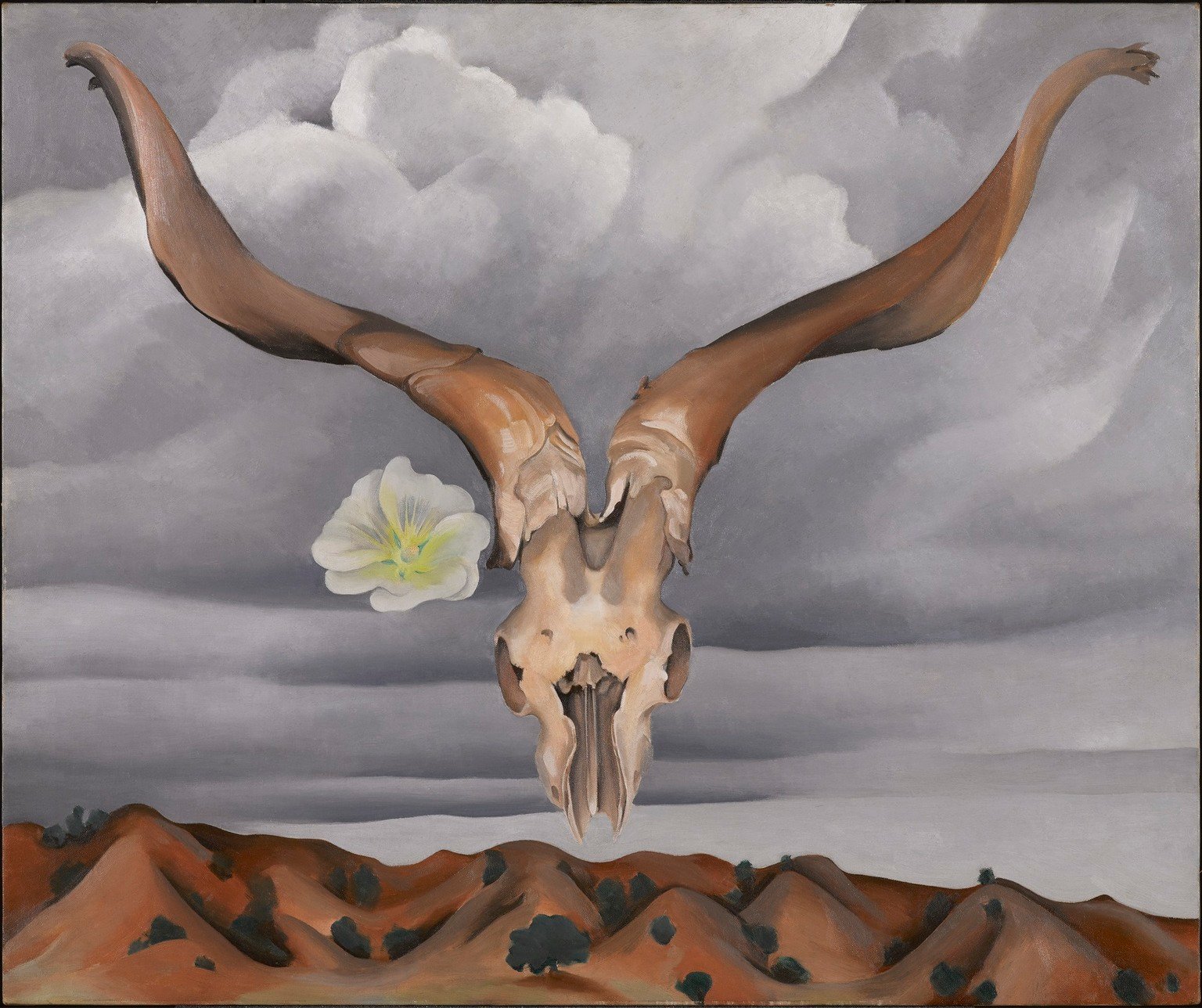

Georgia O’Keeffe’s Ram’s Head, White Hollyhock-Hills can be counted among her most important paintings. In it, the whitened bones of a ram’s skull float weightlessly against the brooding New Mexico skies and a pristine white hollyhock blossom hovers beside it, the Rio Grande Valley hills below.

O’Keeffe was 47 at the time she painted it and regarded as being at the height of her creative powers. She had been living between New York and New Mexico for almost six years (she made her first extended stay in New Mexico in 1929).

O’Keeffe seemed to have a certain special affinity for the painting. She had her framer make a scalloped and punched sheet metal frame for it, inspired by tinware made by the artisans of the Southwest—something she rarely did. Today, it is in the collection of the Brooklyn Museum.

To mark what would have been O’Keeffe’s 133rd birthday this month (November 15th), we decided to take a closer look at this quintessential O’Keeffe image. Here are three facts that might change the way you see Ram’s Head, White Hollyhock-Hills.

1) It Marked a New Chapter

Georgia O’Keeffe pictured with her husband, Alfred Stieglitz. Courtesy of Getty Images.

The years leading up to 1935 had been difficult ones for O’Keeffe, including artistic frustrations coupled with her perpetually tumultuous marriage to photographer Alfred Stieglitz. In 1932, a depleted O’Keeffe abandoned a commission for New York’s Radio City Music Hall and stopped painting entirely. The following year, falling ill, she moved in with her sister before ultimately being hospitalized with a breakdown.

New Mexico and its otherworldly landscapes would prove restorative for the artist, as it had before and would continue to do. In 1934, following her first visit to Ghost Ranch, north of Abiquiú in New Mexico, O’Keeffe would return to painting with renewed enthusiasm—and, with Ram’s Head, White Hollyhock-Hills the following year, ushered in her mature style, which juxtaposed elements with imaginative freedom. (Compare it to her less mystical skulls from a few years earlier.)

The imagery she had long engaged—the landscape, flora, and fauna—appear now synthesized within a composition that does away with earthly logic, in something close to Surrealism. The dissociated images of the Rio Grande Valley, the ram’s skull, and the blossom of hollyhock meet at different angles, scales, and perspectives to mystical effect.

Critics did not miss the painting’s significance. When Ram’s Head debuted in a 1936 exhibition in New York, the New Yorker declared, “In its conception and execution, it is one of the most brilliant paintings O’Keeffe has done.”

2) The Great 1930s Drought Was Key

Arthur Rothstein, The bleached skull of a steer on the dry sun-baked earth of the South Dakota Badlands (1936). Collection of the Library of Congress.

O’Keeffe’s use of animal bones is so familiar now that it may seem timeless. But it was very connected to her historical moment.

During the Dust Bowl years of the 1930s, animal bones could be found dotting the Western American landscape with alarming frequency. A 1934 drought in New Mexico only exacerbated that reality. By the time of Ram’s Head, they were a veritable trope in documentary photography.

For Farm Security Agency photographers documenting the toll of the Dust Bowl on farmers and migrant workers, particularly Arthur Rothstein, the bones of cattle and livestock scattered on dried earth served as a visually striking reminder of the environmental conditions that had precipitated the era’s calamities.

This was the context for O’Keeffe’s bone imagery, which became a signature in the ’30s. Driving her Ford Model A across the desert, she would collect bones with a kind of reverence.

“The first year I was out here, because there were no flowers, I began picking up bones…,” O’Keeffe would recall. “So I brought home the bleached bones as my symbols of the desert. To me they are as beautiful as anything I know. To me they are strangely more living than the animals walking around—hair, eyes, and all, with their tails switching.”

3) It’s About Rebirth, Not About Death

Detail of Georgia O’Keeffe, Ram’s Head, White Hollyhock-Hills.

Clearly hallucinatory image of a haunting animal skull looming out of the desert is about death. Or is it?

While helping to organize her 1936 exhibition at Stieglitz’s gallery 291 in Manhattan, the painter Marsden Hartley, a close friend of Stieglitz, singled out the painting for its remarkable impact. He called the painting, with its innovative juxtaposition of elements…

a transfiguration—as if the bone, divested of its physical usages—had suddenly learned of its own esoteric significance, had discovered the meaning of its own integration through the processes of disintegration, ascending to the sphere of its own reality, in the presence of skies that are not troubled, being accustomed to superior spectacles—and of hills that are ready to receive.

Hartley saw biographical significance in the work, adding that O’Keeffe had succeeded in “portraying the journey of her own inner states of being.” Having moved through the personal and artistic struggles and illness of the proceeding years, O’Keeffe and her art had been transformed—and had reached, in Hartley’s reading, a place of joy and transcendence, having “known the meaning of death of late and having returned with valiance to the meaning of life.”

While the skull is front and center, just as important is the hollyhock. While O’Keeffe herself scorned such direct symbolism, we can note that it traditionally represents ambition, fertility, and fruitfulness, on account of its hundreds of seeds.

Through this lens, O’Keeffe’s vision stands like a kind of artistic apotheosis, rising above the earthly troubles and struggles towards a new vitality.