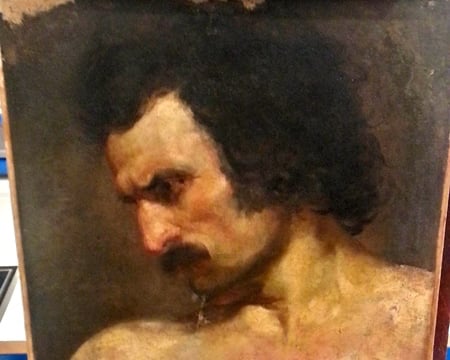

The painting found in the storage rooms of the Rochefort City Museum could be by Géricault.

Photo: Musée municipal de Rochefort

The Théodore Géricault expert Bruno Chenique may have made a major discovery. While shooting a documentary about Géricault’s masterwork Raft of the Medusa (1818-19) in Rochefort, Chenique came across a painting he believes to be by Géricault.

Chenique, a leading specialist on the Romantic master, found the painting in the storage of the Art and History Museum Hèbre de Saint-Clément, in Rochefort, southwest France, where it had been languishing since 1860, Sud Oest reports.

The rediscovered work, which dates from 1811-1812 and measures 62 x 48 cm, is currently in the process of being authenticated.

While making of the documentary, Chenique remembered having seen a black-and-white photo of a painting from the museum’s collection that showed a man in profile. The work was not attributed to Géricault.

He then asked the museum to see the oil on canvas work. When the painting, entitled Head of a man in profile, a former Mamluk of Napoleon I, emerged from storage, Chenique was reportedly overcome “with a positive feeling.”

The painting first arrived in Rochefort in the luggage of Alexander Fiocchi, a Parisian collector, who founded the Municipal Museum of Art and History—of which he was also the first curator—in 1860.

“For nearly a century, the picture remained somewhat forgotten and not identified,” said Florence Lecossois, deputy mayor in charge of culture. Back then, Géricault’s reputation was not what it is today. “One couldn’t care less, really,” said Bruno Chenique.

Géricault’s Favorite Model

In 1955, Michel Laclotte, who was general inspector of provincial museums at the time, and who later became director of the Louvre between 1987 and 1995, compiled a report that referenced the painting as being an “acquisition of a Géricault,” but noted that the author needed to be authenticated.

Fifteen years later, in the early 1970s, the authenticity of many Géricault paintings was being challenged. The painting in Rochefort was one of the works “downgraded” as inauthentic. “This was sometimes done without even seeing the work in question,” Chenique notes.

Last year, however, a not-so-minor detail put this downgraded classification into question. The man seen in the painting was a favorite model of the painter, a man called Gerfant. He is the same model that appears as a dying man on the far left of the Raft of the Medusa, painted seven to nine years after the profile painting.

Well preserved, the early work has undergone an initial “multispectral analysis down to 240 million pixels” by the company Light Technology, which has “strengthened the intuition” of Chenique.

Major News for Rochefort

Florence Lecossois remains cautious for now. Considering how a positive authentication could impact the small city of Rochefort, she doesn’t want to jump the gun on this potential treasure of 19th century art heritage.

For Chenique, however, it wouldn’t be a life-changing event. The Géricault expert has already authenticated dozens of works by the French master, bringing the number of paintings attributed to him to 300.

Read about other recently rediscovered paintings by masters:

Unknown Goya Self-Portrait Discovered Languishing in French Museum

Disputed Van Dyck Self-Portrait Genuine After All and Goes on Display