The realities of today’s refugee crisis have been thrown into sharp relief by President Trump, who on January 27 signed an executive order temporarily banning refugees from entering the country. The heavily-criticized measure is sure to become fodder for artists whose work explores issues of displacement, but in the meantime, there’s still time to catch Halil Altindere’s current exhibition at New York’s Andrew Kreps Gallery, a show which now seems almost prophetic.

“Space Refugee,” and the film of the same name, is inspired by the life of Muhammed Ahmed Faris, a Syrian general who became his country’s first astronaut when he served on a roughly eight-day mission to the Soviet Union’s Mir space station in 1987. Twenty-five years later, Faris, in defiance of the Assad regime, fled the country and became a refugee. He also became the highest-ranking Syrian defector to date. The former astronaut eventually wound up in Turkey, where he met Altindere.

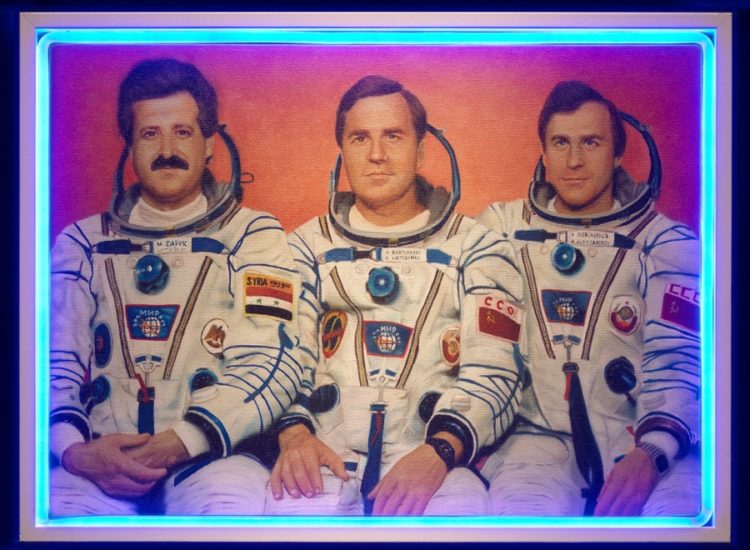

For the artist, Faris’s story serves as an opportunity to imagine the possibilities of the final frontier as a solution to the problem of refugees. The show, which appeared at Berlin’s Neuer Berliner Kunstverein in 2016, includes a virtual reality headset that deposits the viewer on the surface of Mars, in the center of a refugee colony, and two portraits of Faris, one a Photoshopped image of a space walk, the other a heroic painting with his fellow crew members, Soviet cosmonauts.

The centerpiece of the exhibition is a video featuring archival footage of Faris’s time in the space program, paired with present-day interviews about his experiences as a refugee. Once a national hero, in both the USSR and in his native Syria, Faris is now a man without a country—and now, thanks to the executive order, he couldn’t visit the exhibition inspired by his story even if he wanted to. (While the ban extends to six other nations, Syria is the only one that is affected indefinitely, rather than for a 90-day period.)

Halil Altindere, installation shot of “Space Refugee” at Andrew Kreps Gallery. Courtesy of Andrew Kreps Gallery.

The exhibition throws our national concerns into stark relief. “We will build space and I will go with them to Mars, where we will find safety and freedom,” intones the narrator in Space Refugee. “Where is freedom on Earth? There is no dignity for humans on Earth.”

The speculative film features a man and two young children, all in Palmyra-branded space suits, adjusting to life on Mars. In interviews conducted via Skype, experts from NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory explain how scientists and engineers might one day successfully complete a manned mission to the Red Planet.

Though the idea of sending refugees to Mars is completely absurd, watching Space Refugee is an interesting exercise that helps put the current crisis in perspective. As Faris himself put it, speaking to the Guardian, “when you have seen the whole world…there is no us and them, no politics.”

“Halil Altindere: Space Refugee” is on view at Andrew Kreps Gallery, 535 West 22nd Street, January 7–February 18, 2017.