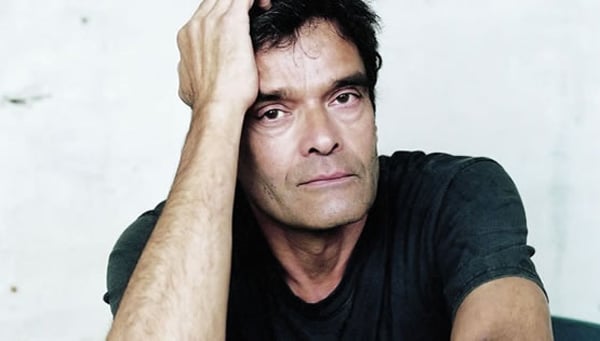

Photo via: Schwarz Foundation

Still from Harun Farocki’s Inextinguishable Fire (1969)

The German filmmaker, theorist, and artist Harun Farocki, who died today, is a towering figure, and one whose influence is bound to grow. Like his art itself, his influence is powerful but subtle; the fact that I think so much of him almost surprises me. In his films Farocki specialized in brainy self-reflexivity with a social conscience, weaving together found footage and documentary conventions, turning images over and teasing out the glimmering, sinister kernel in them.

Born in 1944, Farocki came of artistic age in the 1960s, when cinema was entering into a spasm of self-criticism amid the political disenchantments of the era. His first artistic and political commitments were to the anti-Vietnam War struggle, and the surreal collision of politics, technology, and cinema was a frequent focal point in his work. The theme continued through his 90-plus films to his recent series, Serious Games 1-V, shown at the Museum of Modern Art in 2011, a suite of films that capture the various ways that the US military uses videogame-like simulations to train for its operations; how, in other words, technology has literally turned war into a game.

This morning, when the news came in of his passing, I went back and watched one of Farocki’s first films, Inextinguishable Fire, from 1969, a grainy cinematic essay that reflected on the then-still-unfolding catastrophe of the Vietnam War. The oft-cited opening sequence of this early work is vivid and complex in a way that few works of video art achieve. A young Farocki is pictured, sitting at a desk. He reads, in a steady voice, from testimony from a Vietnamese boy who was disfigured by a US napalm attack. Then he looks up into the camera and says the following:

How can we show you the injuries caused by napalm? If we show you pictures of napalm burns, you’ll close your eyes. First you’ll close your eyes to the pictures. Then you’ll close your eyes to the memory. Then you’ll close your eyes to the facts. Then you’ll close your eyes to the entire context. If we show you someone with napalm burns, we will hurt your feelings. If we hurt your feelings, you will feel like we’d tried napalm on you. We can give you only a hint of how napalm works.

And then Farocki takes a lit cigarette and snuffs it out on his own arm. “A cigarette burns at 400 degrees,” a narrator says. “Napalm burns at 3,000 degrees.”

There are many other Farocki works that stick in the brain: Videograms of a Revolution (1991), with its look at how the carefully choreographed image of a Communist dictatorship came apart on TV; Workers Leaving the Factory (1995), gathering images of labor in film history; Creators of the Shopping Worlds (2001), which turns a documentary about shopping mall design into an intellectual fever dream about the suffocation of the world under corporate dictates.

But as Thomas Elsaesser once suggested, this simple opening sequence from Inextinguishable Fire already captures what is great about all of Farocki’s work: the wary interrogation of art, combined with the sense of urgency of reality; intellectual intensity combined with a quietly concussive emotional payoff.

You can watch Inextinguishable Fire below: