Five hundred years on, and its all about Bosch. With dozens of books published on the Flemish painter, new scholarship, and major museum exhibitions, the impact of the artist on popular culture is undeniable.

A sure sign of one’s status is receiving the big screen treatment, as he does in the 2015 documentary film Hieronymus Bosch: Touched by the Devil. The camera lovingly pans over the paintings, but the real drama are the competing museum exhibitions and how they will work together. When the artist’s hometown museum, Noordbrabants asked Madrid’s formidable Prado if the singular The Garden of Earthly Delights could be loaned, the answer was “it [is] much too fragile to travel.” Of course it is.

Hieronymus Bosch. The Last Judgment. Courtesy of Museo Nacional del Prado.

Like thousands of other fans, I went to Madrid to view what colleagues are calling the definitive exhibition of an artist whose stature has only grown with each passing century, and yet remains a mystery. We ask ourselves over and over again, how did he come up with that? Was he prone to visions, or was it that the molding bread of his day contained hallucinogens?

I arrived at the Prado last week with high expectations. There are number of things like queues, timed tickets, and pacing that could have been logistical nightmares; all were avoided with military precision. Clear signage outside and inside the museum was accompanied by proactive visitor service staff.

The exhibition design team is to be applauded for creating a space that trusts visitors by organizing the triptychs on curving platforms, that not only direct circulation in a gentle, meandering manner, but allowed us to be a foot and half away from these masterpieces. This closeness is a key detail, considering the size of the work. The content is monumental, the craftsmanship impeccable, but the scale is relatively modest. Through this platform approach, I was close enough to see single strokes that connoted a wisp of hair, a strand of wheat or an animal in the distance in the artist’s painting The Adoration of the Magi.

Making my way through the exhibition, in which paintings, drawings and etchings are distributed in seven themed-galleries, quiet whispers in Spanish, Japanese, French, and English betrayed the same delight and surprise I was feeling. Each of us had our own booklet that contained extended captions for each work, thus avoiding crowding around wall labels that often can create bottlenecks.

Hieronymus Bosch. The Haywain Triptych. Courtesy of Museo Nacional del Prado.

In front of The Haywain Triptych (1512-15) I was bombarded with disturbing fantastical anthropomorphic beings over which ethicists and scientists would have a field day; fish with arms, a woman whose lower half is snake, insects with human bodies, men whose feet are claws, a deer that walks on his hind legs, and a whiskered mouse with wings. These chronological panels showcase the birth of hell, and I start to free associate with such alacrity, seizing upon the genetic code for J.M. Barrie’s Tinker Bell, Walt Disney’s 1940 animated film Fantasia, and James Cameron’s Na’vi tribe in Avatar (2009), human creatures with aquatic coloring and long tails.

Every day objects become major architectural interventions of habitation in The Last Judgment Triptych (1505-15). In the central panel, pitchers, vases, saucers, funnels, and knives are wackily out of scale, some balancing on top of each other creating a bizarre landscape of hell. It’s a leap (but this is what Bosch does to you) that Fischl & Weiss series of photographs entitled Equilibres (1984) of kitchen objects balanced before collapse are a distant relative.

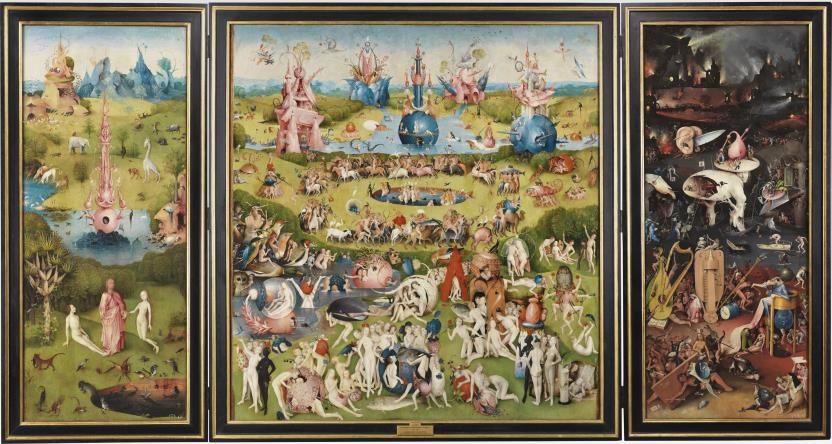

The pièce de résistance is none other than The Garden of Earthly Delights Triptych (1490-1500), a painting in Spanish hands for almost five hundred years as King Phillip II amassed the largest collection of Bosch’s work. You are immediately struck by the denseness, the vibrant gaudy color palette, and yet how contemporary this painting remains. In the much contested middle panel two polar interpretations are often cited: was it meant to be an allegory of near sins of erotic pleasure that would lead you to hell or a vision of a peaceful, idealized world of neighbors cavorting in harmony? With the US presidential elections upon us, we continue to struggle with what our nation, what our communities should look like.

Hieronymus Bosch. The Ascent of the Blessed. Courtesy of Museo Nacional del Prado.

I had studied much of Bosch’s work in reproductions but it was the forth panel of Visions of the Hereafter: The Ascent of the Blessed (1505-15) that stopped me cold in my tracks. The dark painting depicts angels rising and escorting humans through a tunnel of spiraling white light. We’ve seen this hokey image too many times in Hollywood’s romantic comedies but here in the Prado, my body began to tingle. The vertical composition is naive and yet he creates a depth of otherworldliness that is utterly convincing. So convincing it is possible that filmmakers working in Virtual Reality should start here for a blueprint.

Days later, I cannot stop reveling in Bosch’s mise en scène—the hybrid creatures both grotesque and humorous, the out-of-scale ambition, the perverse religious storytelling, and how this work presages so much of our culture today.

The summer art shows have been ripe with the Bosch aura, from Raqib Shaw’s White Cube solo exhibition to Swizz Beatz’s No Commission art and music festival in the Bronx, where artists like Jacolby Satterwhite, Kristen Liu-Wong, and Saya Woolfalk conjure otherworldly realities. Bosch repeatedly painted fish that fly, fish that dress up, and fish that seem to converse with humans, which is none other than the template for Finding Dory currently dominating the box office. It’s an explosion of kinships that are thrilling and exasperating.

In the end, I wondered: Am I connecting actual dots or does the ambiguity play tricks on my mind? Does the inherent mystery create fluidity so that each generation who views his paintings arrives at the same conclusion: his work endures for all time?

If you want to get high on art, bliss out, this is it.

“Bosch: The 5th Centenary Exhibition” at Museo Nacional del Prado, in Madrid, Spain has been extended until September 25, 2016.

Karen Wong is the Deputy Director of the New Museum.