The Swedish visionary artist Hilma af Klint (1862–1944) spent her lifetime working in relative obscurity. Born the daughter of a naval captain, af Klint attended the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Stockholm, where she graduated with honors. While she publicly exhibited and sold elegant landscapes and botanical works, she privately devoted herself to large-scale biomorphic and richly colorful abstract works that attempted to capture the essences of her complex spiritual and cosmic beliefs.

A student of theosophy and Rosicrucianism, af Klint believed in a world beyond the veil of human consciousness, filled with spirits and otherworldly entities, and in reaching to convey these forces, her artistic style stretched beyond convention. In recent years, she has come to be regarded as one of the first Western artists to create works based on abstract forms, painting a series of esoteric, constellation-like works she called Primordial Chaos in 1906, years before Wassily Kandinksy or Kazimir Malevich, the long-hailed progenitors of abstraction, did anything similar.

Af Klint’s work met with consternation in her own day and the artist seemed aware that future generations might be more willing to consider it. With her passing, she left instructions to her nephew that none of her works should be displayed until 20 years had passed from her death.

The art world took a fair bit longer than that appreciate her vision, however. Her entire oeuvre was offered to the Moderna Museet in Stockholm in 1970, a gift the museum refused. In wasn’t until 1986 that several of her paintings were included in the exhibition “The Spiritual in Art” at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, and af Klint finally received her first solo exhibition in 1988 at the Nordiskt Kunstcentrum in Helsinki. For many art lovers though, it was the Guggenheim Museum’s blockbuster 2019 retrospective “Hilma af Klint: Paintings for the Future” in New York that made her a familiar name.

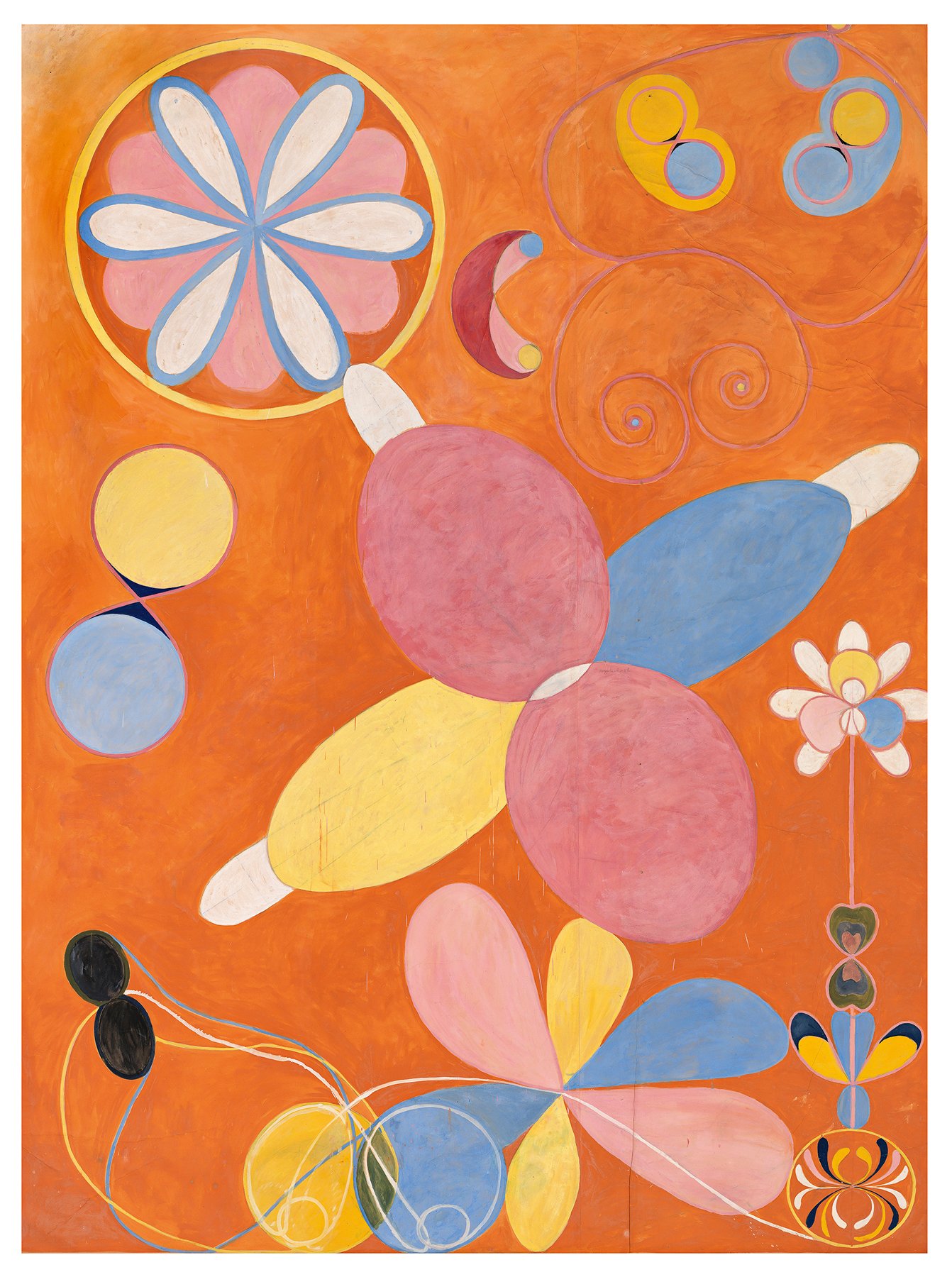

That dazzling show brought together more than 70 of her paintings. One of the most striking works was The Ten Largest, No. 4 Youth (1907), a towering canvas measuring 11 feet high and 7.5 feet wide. Shapes like stars and satellites, drawn in planes of pinks, yellows, pale blues, and white, swirl against a vivid orange background. The forms seem detached from gravity, and viewers could imagine them floating in the vastness of outer space or some primordial expanse.

The painting belongs to a series known as “The Ten Largest” (1907), made in oil, tempera, and paper, which are among af Klint’s most magnificent works, and which she created over the course of 60 impassioned days.

Recently, David Zwirner announced it would be opening a new show of recently discovered drawings from Hilma af Klint’s “Tree of Life” series on November 3. Ahead of that show, we decided to take a closer look at one of af Klint’s most famous paintings and offer three facts that might change the way you view her work.

1) The Painting Was “Commissioned” by Spirits

Hilma af Klint in her studio at Hamngatan, Stockholm, circa 1895. Courtesy of Stiftelsen Hilma af Klints Verk. Artist Anonymous. Photo by Fine Art Images/Heritage Images via Getty Images.

While a teenager in Stockholm, af Klint became a member of a mystical group known as the Five. Along with four other women, af Klint would participate in séances that would provide her with artistic inspiration. Many of the women claimed to have received communications from supernatural beings, which they scrawled out in notebooks in a form of automatic drawing.

Ultimately, six discernible entities were identified: Amaliel, Ananda, Clemens, Esther, Georg, and Gregor. Over the course of their acquaintance with the Five, the spirits let it be known that they wanted to build a temple—one filled with paintings. While the other women in the group thought the commission was too dangerous and could lead to madness, af Klint accepted it, and from 1906 to 1915 she would churn out painting after painting, ultimately creating 193 works. The Ten Largest, No. 4 Youth is among the works meant for the temple, and for which the artist made no preparatory drawing.

2) “Youth” Can Be Read as a Stage in Spiritual Development

Installation view, “Hilma af Klint: Paintings for the Future.” Photo by David Heald, ©Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation.

“The Ten Largest” series is divided into groups based on the various stages of life: there are two titled Childhood, two titled Youth, four titled Adulthood, and two more with the name Old Age. While many works throughout the history of art have alluded to similar growth cycles—often using the metaphor of the seasons—af Klint’s can be read as tracing spiritual rather than physical development.

The paintings of Childhood and Youth are filled with bright colors, numerous squiggly details and sometimes even words, both nonsensical and familiar (in af Klint’s world, blue alluded to femininity and yellow to masculinity). Her other Youth painting in the series includes the phrases “ave maria” painted in loopy curls, and as art critic Peter Schjeldahl wrote in New Yorker magazine, this “may allude to Catholicism as an immature phase of spiritual growth.”

The paintings, which were intended to hang along the walls of the temple, could also be viewed as a non-Christian Stations of the Cross, freed from bodily passion and pain, and instead emphasizing a more abstract, internal rebirth.

3) Botany and Scientific Discoveries Influenced Her Visions

Hilma af Klint, Cress (1890s). Courtesy of Albin Dahlström, the Moderna Museet.

Though interpretation of af Klint’s works leans heavily on the otherworldly (and for good reason), the artist was deeply engaged in scientific studies too. Af Klint was a vegetarian and—unlike many others in her day and age—believed in the theory of evolution. She spent years creating professional botanical drawings, studying particularly the contributions of Swedish botanist Carl Linnaeus.

Floral forms fill The Ten Largest, No. 4 Youth, from petal-like halos to stamen-like shoots. Af Klint also closely followed scientific developments emerging in her own time, including the discovery of electromagnetic waves in 1887 and gamma rays in 1900. She was also known to have been fascinated by the discovery of subatomic particles; the electron was first identified in 1898, and in 1904 scientist JJ Thomson proposed the structure of the atom as a sphere of positive matter in which electrons are suspended by electrostatic forces.

Detail of Hilma af Klint’s The Ten Largest, No. 4 Youth (1907).

Af Klint’s radiating waves and atom-like shapes certainly owe some debt to the natural world and her close engagement with it. Her work can be seen as melding organic forms with imagery culled from religious symbolism, like halos and mandorlas. Rather than working in opposition to one another, these two creative sources have a symbiotic existence in af Klint’s work, with scientific discoveries unveiling the evidence of spiritual worlds invisible to the human eye.