Two years ago, Justin Wong was a famous newspaper cartoonist in Hong Kong. He was known for his political drawings, and taught as an assistant professor at an art school. But all this ended abruptly when it became clear that some of his work could render him in trouble with the authorities.

First, Wong quit his newspaper column after it was publicly criticized by the police; then he fled to the U.K. in December 2021, after hearing that his university had allegedly reported him over an academic article he wrote analyzing the visual symbols of the 2019 pro-democracy, anti-government protests—the largest political movement the city has seen since it was handed over to China from Britain on July 1, 1997, which marked the end of the British colonial rule of the city after one and a half centuries. The university denied the allegations.

Ever since, he has been forging a new life for himself in London. And the new year has been a busy one. He is putting the finishing touches on plans for an exhibition in early February, while preparing for the launch of a new online arts education platform offering programs for Cantonese-speaking Hong Kongers around the world, taught mainly by Hong Kong artists and art educators like himself who have relocated overseas.

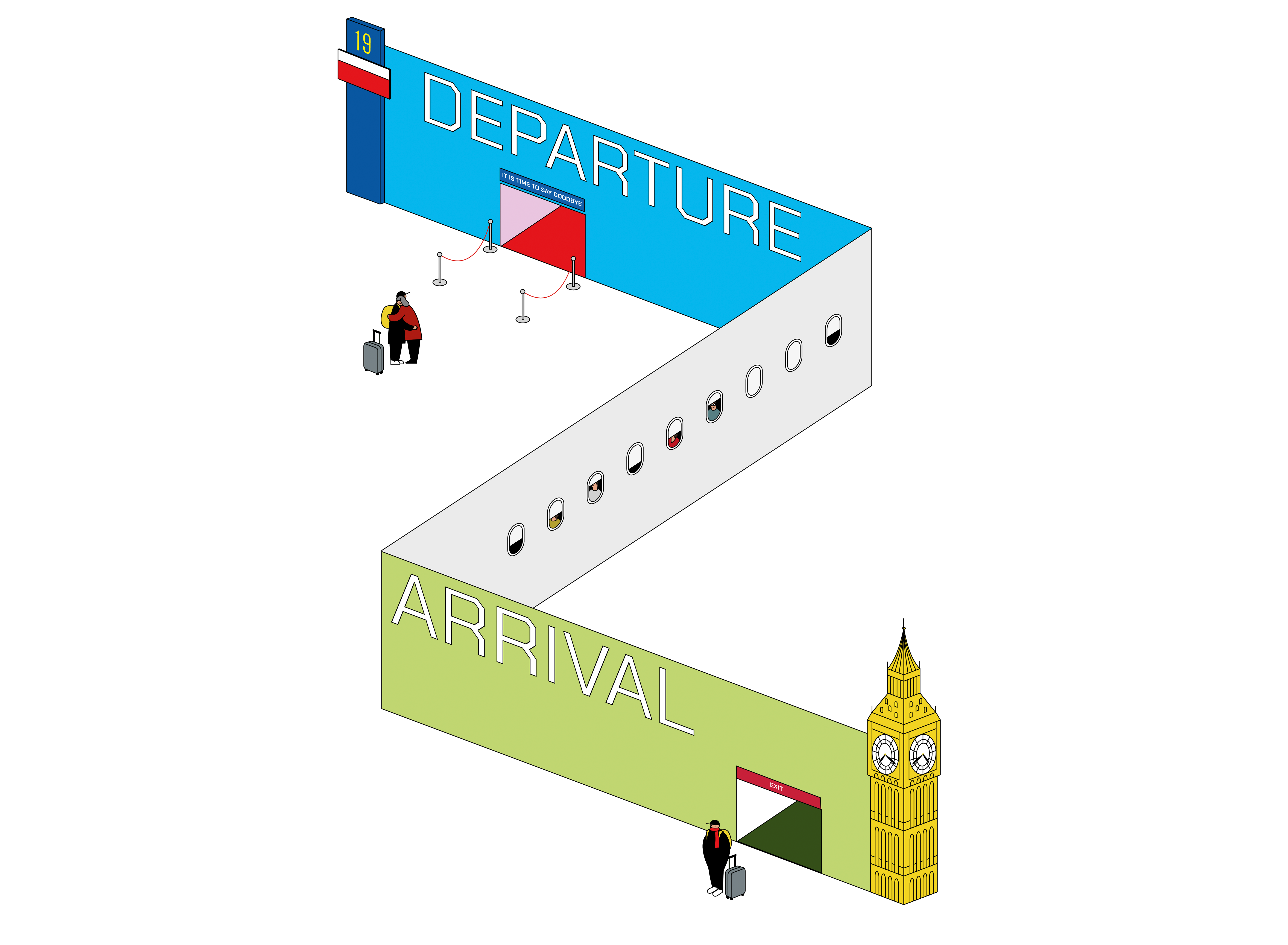

A new illustration from the series From Home to Home by Justin Wong. Courtesy of the artist.

It has taken some time for Wong to find his feet in his new home. “To work as an artist in Hong Kong, connections are very important, whether you are getting funding from the government or working with galleries. Like many artists who have relocated to the U.K., I lost all these connections when I left,” he said.

Yet surprisingly, he spoke of feeling “liberated” in his art practice. Rather than focusing on the day-to-day socio-political issues of his hometown, life as a member of the Hong Kong diaspora has become the inspiration for his new projects. He has returned to woodblock printing, his main practice during his art school days. While experimenting with his newfound freedom, he has created the “Little Pink Man” series, which taps into the emotional struggle experienced by many Hong Kong migrants. “Indeed, we need time to reflect on this,” he noted. “This is an era of diaspora, so there should be art of the diaspora.”

Wong is one of many of artists and cultural workers creating new lives for themselves abroad following the enactment of a national security law on June 30, 2020, implemented to curb the 2019 protests, and under which certain cultural gatherings and expressions could be regarded as politically sensitive.

As they are settling in their new homes, a new diasporic Hong Kong art community also begins to take shape. This is the most obvious in the U.K., which now has the biggest Hong Kong diaspora community. Home Office data shows that 184,700 British National Overseas visas, introduced in 2021 to offer a pathway to citizenship to Hong Kongers born under the British rule as well as their dependents, have been handed out as of September 2023. Among them, 135,400 have arrived in the country. There is no detailed data to show exactly how many of them are in the art field, but there’s no lack of artists, curators, art administrators, and art educators across different regions in the country.

“The reason for most of the artists moving to the U.K. is the political situation in Hong Kong, as it concerns the pressure on freedom of artistic expression and creation,” noted Charles Wong, an independent curator and arts administrator who relocated to the U.K. in the summer of 2021.

Polam Chan’s sculpture featured in exhibition ‘Confronting the Disappearances’ curated by Charles Wong. Courtesy of the artist.

In the case of the U.K., this community is a lot more nuanced and layered because it includes many non-BNO Hong Kongers. They include ethnically non-Chinese art workers who used to live in Hong Kong, art students who decided to remain in the country upon graduation, those who were born locally to parents of Hong Kong descent, and those who moved to the country since a young age, reflecting the close ties forged between Hong Kong and Britain during the colonial times.

Still, as a result of the mass emigration, the past year saw a growing number of exhibitions and events, active social media groups and meet-ups, allowing them to connect. While most shows have been staged by political or activist groups, and works that get the most publicity are political art, more artists and cultural workers are working on shows and projects that showcase the many other dimensions of Hong Kong contemporary art in this new context.

Charles Wong curated and co-organized three exhibitions featuring works by Hong Kong contemporary artists living in the U.K. last year. Most of the exhibited works ranging from sculptures, photography, and moving image. Created shortly after the 2019 protests, many of the artists were responding to the political turmoil they had experienced back home. But this is changing.

“Some artists are shifting their subject from describing the collective memory of the Hong Kong protests to self-identity as a diasporic artist,” Charles Wong observed. “In their works, they explore the connections and attachment with Hong Kong that remain or have been relinquished. The works may also carry a sense of living in exile or being banished.”

Documentation image of a map made by C&G Artpartment noting all the streets of the same names in Sheffield and Hong Kong for project Harcourt Road. Image courtesy of the artists.

Artist and curator Clara Cheung, on the other hand, has been actively exploring the new diasporic identity and the historical roots of the former British colony. Cheung, who was elected as a district councilor in 2019 during the heat of the protests, was forced to resign when councilors were asked to swear a new oath of allegiance to the authorities following the crackdown of the protests. She subsequently relocated to the U.K. and in her new home in Sheffield, she discovered its uncanny connection with her hometown—Hong Kong and Sheffield share many street names.

The result of this discovery is Harcourt Road, an expansive ongoing project by artist duo C&G Artpartment formed by Cheung and Gum Cheng. In Sheffield, Harcourt Road is a residential street, but in Hong Kong, Harcourt Road was a battleground for many major protests, from 2014’s Umbrella Movement to the 2019 protests. The duo has set out to research the comparative histories of the two streets and stories about migration, with a new exhibition planned for September this year. Cheung also took part in “Hong Kong Future Diaspora,” a project initiated by Eelyn Lee, a U.K.-based artist and filmmaker with Hong Kong and English heritage.

“Just like many other Hong Kong migrants, I’m new to this country. Deep down I still hope that one day I can return to Hong Kong and rebuild the city. But then, I may not have a chance to return, and I will remain as diaspora for good,” Cheung noted.

On January 30, the Hong Kong government launched the consultation of new national security laws targeting foreign agents and activities deemed as endangering national security, which may include arts and culture activities.

“I hope to maintain my connection with artists who are still in Hong Kong. But at the same time, working with artists based here through these projects is also rewarding. It’s a great way to get connected with the local art circle, and there’s a lot we can share because they care about Hong Kong.”

Artist Martin Lever at his London solo exhibition ‘Silent Protest.’ Photo by Vivienne Chow

And the community being built has created space for Hong Kong artists to thrive.

Twenty five-year old Polam Chan changed his mind about returning to Hong Kong after graduating from his sculpture studies with a master’s degree at the Royal College of Art in London in 2021. “I’m feeling a sense of community here,” he said. Although his work draws inspiration from his hometown’s society, he feels it is easier to make art in the U.K. “I can say whatever I want,” he noted, adding that there has been plenty of opportunity to exhibit here.

Martin Lever, a Briton who had lived in Hong Kong for 44 years since the age of nine, returned to the U.K. with this family in May 2022. While the draconian Covid restrictions played an instrumental role in Lever’s decision to leave Hong Kong, the taste of censorship had also soured the sweet life of the city. At the 2021 edition of the Affordable Art Fair where he showed a series of works titled Above the Protests, he was “advised” by an unnamed source to change the title into something else. “People are being nervous and starting to self-censor, worried about being controversial. It’s a very worrying trend,” he said.

In the U.K., he felt that such pressure is off. In December he held his first solo show in London titled “Silent Protest,” showing a variety of prints and canvas works including a series taking a Keith Haring-esque aesthetic riff on famous revolutionary quotes from Chinese communist leader and founder of the People’s Republic of China Mao Zedong. The work could be deemed “subversive” in Hong Kong’s post-national security law context, but here, the three-day selling exhibition attracted over 700 visitors, and he sold 120 prints and three canvas works.

Installation view of A Place Nobody Knows solo exhibition of Kat Yiu Jasper at Saan1 in Manchester. Courtesy of the artist. Photo by Lisa Portinari.

While Hong Kong artists have found a home in the U.K. they are also encountering challenges. There’s a relative lack of funding and resources, as well as exhibition venues, compared to back home. Meanwhile, there is the bigger problem of the lack of a contemporary art context for Hong Kong art in the U.K. Galleries in the U.K. remain out of reach to some Hong Kong artists, who have to rely on galleries back home or in Asia for exhibition opportunities. So far, most of the exhibitions of Hong Kong artists in the U.K. have been political and staged by political and rights organizations, such as Amnesty International and other Hong Konger community groups. However, the majority of the diasporic Hong Kong artists living in the U.K. do not engage in political art.

“These exhibition organizers do not come from the art circle. The advantage of this kind of exhibitions is that they are easy to attract people’s attention. But after a while, you see similar type of works over and over again. We need museums, institutions, and galleries to offer an art context for Hong Kong artists, but this has yet to happen,” artist Justin Wong commented.

Getting noticed by the U.K.’s art circle is another challenge. But some are trying to cross-pollinate the communities through initiatives like artist-in-residence programs such as that at Schoeni Projects, a London-headquartered contemporary art platform founded by Nicole Schoeni, who inherited her family’s legacy of Schoeni Art Gallery, formerly an important gallery based in Hong Kong. The Alter Space at London’s Brick Lane area is a new commercial gallery opened by Bede Ngan, a former advertising executive and collector from Hong Kong who wants to promote art from his hometown and Asia in Europe.

Saan1 (the Cantonese prononciation for mountain) in Manchester, which has a sizable Hong Kong community, is a hybrid of a project space and exhibition venue for hire at an affordable rate. It has also been working with locally-based artists as well as artists from Hong Kong.

“I want my space to be an art space first,” Saan1 founder Kan Cheng said. “I won’t say no to exhibitions containing political messages but I want to focus on what Hong Kong artists are doing, and showcasing Hong Kong art.”