For an artist, addressing this unprecedented moment in history might feel both necessary and daunting. Distilling the complexities of any era while that era is still playing out isn’t easy, and, historically speaking, many works of art that have come to represent a significant point in time were made later—often addressing not the moment itself, but the conditions it incurs.

And yet, intimidating though the task may be, artists can’t seem to help themselves—making art in reaction to the world is what they do. And, in this particular case, they also happen to be locked in their homes with little else on their plates.

There’s no one way to define “Coronavirus art.” A number of artists of Asian descent, such as Taeyoon Choi, Lisa Wool-Rim Sjöblom, and Laura Gao are confronting the latent racism in pandemic panic through illustration. Photographers are making ad-hoc still lifes with a quarantine flair, or taking somber portraits of people from outside. Street artists the world over are filling their neighborhoods with coronavirus-themed designs. And online “museum” dedicated to “art born during Covid19 quarantine” has even popped up.

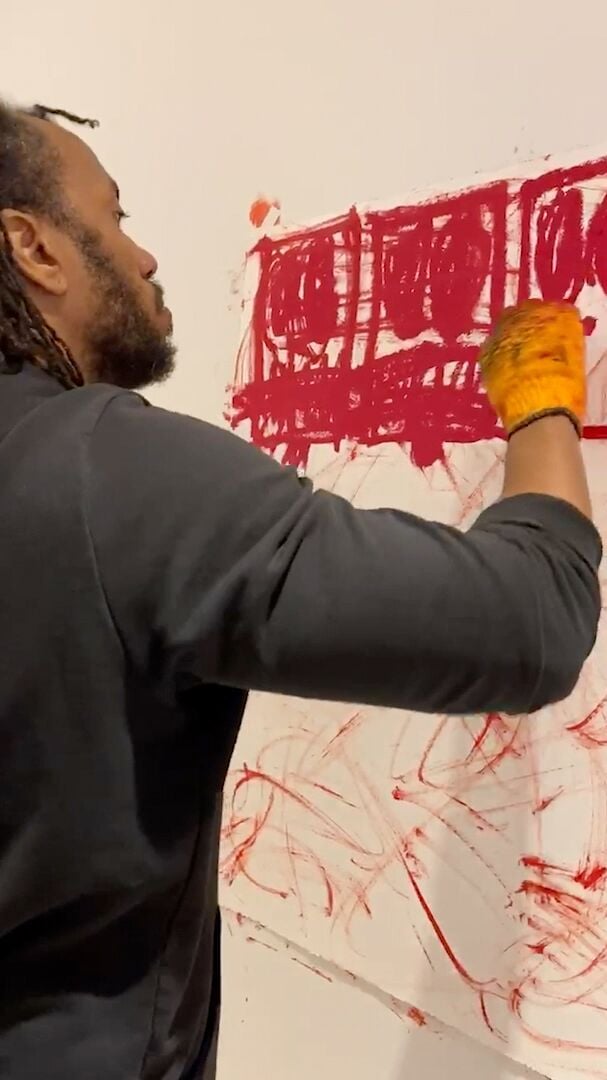

“It’s tough,” says artist Rashid Johnson of the current moment. Holed up in a Long Island house with his wife (the artist Sheree Hovsepian), their son, and his in-laws, Johnson has churned out a series of disquieting oil stick drawings in a makeshift basement workspace. They works are on view now in an online exhibition at his gallery, Hauser & Wirth.

“They’re not the most joyful things I’ve ever made,” he says. “They’re not intended to be illustrations of a time and space, but rather of a feeling. And that feeling isn’t the most comfortable.”

Rashid Johnson, Untitled Anxious Red Drawing (2020). Courtesy of Hauser & Wirth.

An evolution of the artist’s “Anxious Men” series, which features boxy figures scrawled in black, Johnson’s new drawings series are rendered solely in red.

“I just felt like that was the color,” he says. “I wish I had a more philosophical position to take on it, and I could probably conjure one if I wanted to. But to me, that color just looked like what I felt and I think what a lot of people were feeling, which is this sense of urgency and fear.”

Johnson’s new “Untitled Anxious Red Drawings” are also more abstract than their figurative forebears. They’re messier, more menacing—a result of his effort to “deconstruct the image” through almost automatic mark-making. His description of the process feels itself like a response to the present moment’s new rules of distance: “Rather than having a grand commitment to separation and delineation, I’m really focused on the gesture and stretching out the abstract mark-making to find holes in the space.”

George Condo with his work Linear Contact (2020). Courtesy of the artist and Hauser & Wirth.

Meanwhile, working out of a garage in the Hamptons, George Condo has produced a new body of paintings and drawings that channel the idea of social isolation through cubist abstraction, an approach that conjures a world mediated by screens as much as it does the history of modernism.

“I’m hoping they depict the moment where figures are forced to be separated from loved ones, as I am, and that they show the never ending power of the human imagination,” the artist says of his “Drawings for Distanced Figures,” which are also on view in an online exhibition.

Human connection, or the lack thereof, is a predominant theme in many artists’ work right now. “Coronavirus art” is rarely that; more often it’s art in the time of coronavirus. It’s human art positioned against the backdrop of a pandemic.

Elinor Carucci, Love in the Time of Corona (2020). Courtesy of the artist.

For New York-based photographer Elinor Carucci, the urge to make work in the moment is stronger than the urge to make sense of it. “I never stopped to think, ‘Oh, this is an interesting time. Should I make a project?’ Who knows!” she says. “I can’t even think about it in the usual project terms. This is not like anything else I’ve done before.”

Carucci, who put out her fifth book, Midlife, last fall, often spends upwards of a decade working on a single body of work, during which time she’ll wait to share individual images until she’s completed the project as a whole.

But over the last five weeks, the artist has taken to Instagram to share a series of photos that capture the little details of lockdown life in her Chelsea apartment: video-chatting with her parents for Passover, a tear-soaked tissue left on the couch after watching the news, a mask marked with a faint lipstick trace.

“This is the first time in my life where I’m posting almost every day, and it’s the work I did today or yesterday or maybe two days ago,” she says.

Surprisingly, Carucci says, “I think the people who have been following my work have never been so close to me.”

For now, it’s safe to say that many artists, like the rest of us, are just waiting to see what happens next, how the pandemic will unfold and change life as we know it.

“I’m just trying not to avert my eyes, to be present in the world that we’re living in,” says Johnson. “As an artist, I’m trying to express myself without being didactic, without pandering, and with a sense of presence and thoughtful engagement during the course of something that we’re all experiencing.”