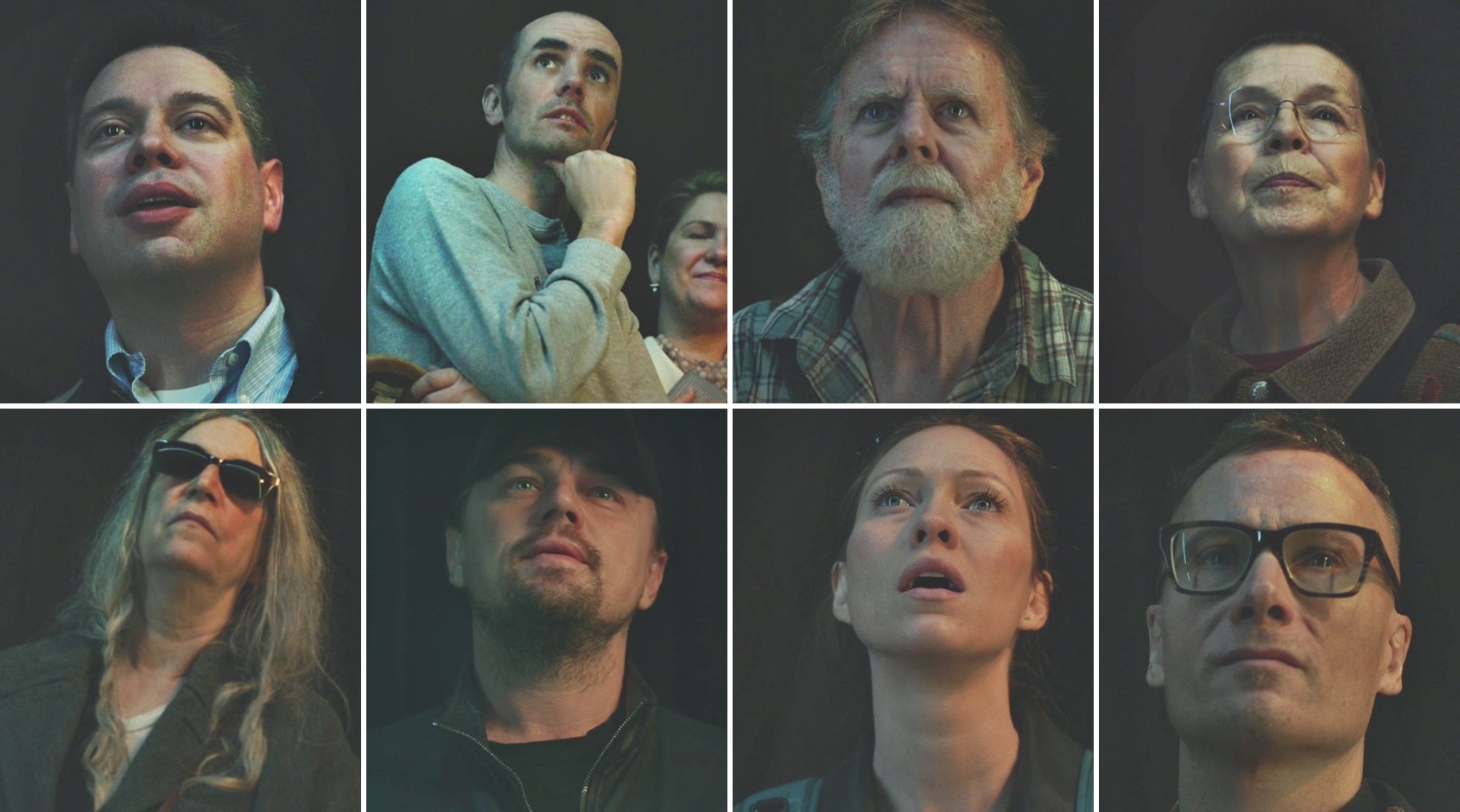

Ahead of last month’s $450 million sale of Leonardo da Vinci’s Salvator Mundi, Christie’s installed a hidden camera near the painting that captured the teary-eyed gazes of visitors beholding the masterpiece.

The advertising agency Droga5 then edited the footage with photographer Nadav Kander into a video montage of awestruck faces, set to a dramatic Max Richter violin soundtrack. They said the video offered “a picture of the overwhelming emotion that this painting, its beauty and its divine subject matter stirred in all who came to see it.”

The ad agency and Christie’s, which posted the video on its website, understood that emotions play a central role in establishing a work of art’s value—a theory that has recently been backed up by science. Two new psychological studies have examined the influence that emotions have on both observing art and making it.

While we have long known that traits such as intelligence and open-mindedness are correlated to creativity, less is known about the role that emotional factors play. But as it turns out, individuals with high emotional intelligence are more likely to be creative than those with a lower emotional IQ, according to a study recently published in the journal Imagination, Cognition, and Personality.

To quantify the relationship between these two attributes, researchers coupled a popular test to determine emotional intelligence with, yes, a New Yorker caption contest.

To begin, psychology experts from the State University of New York at New Paltz evaluated the emotional intelligence of 265 participants by giving them a series of photos of people’s eyes and asking them to guess each person’s mood, a common test known as “Reading the Mind in the Eyes.” This determines what is known as “empathic accuracy,” or the ability to correctly read the emotions of others.

Afterward, the researchers showed participants two New Yorker cartoons—one of a man in a suit about to be shot out of a cannon, and the other of the Grim Reaper in a baseball field—and asked them to write captions for each. (It’s not a coincidence that the researchers chose cartoons for this experiment: “Given how central emotional processing and expression are to all facets of humor, we expect emotional intelligence to positively relate to humor production,” they write.)

Three judges then rated each of the captions using 10 criteria believed to be components of creativity, including funniness, sophistication, originality, and imaginativeness.

In the end, those who accurately identified the moods from the photos also tended to receive high scores on the caption contest.

The findings “demonstrate a strong effect for the empathic accuracy (emotion-detection) element of emotional intelligence to positively predict creativity,” the study says. “This pattern is particularly interesting given that empathic accuracy is a social-detection process whereas creativity is a generative process.” Being sensitive, it seems, really does make help you make better art.

The researchers also tested how various personality traits correlate to creativity. In one unusual finding, they discovered that participants who rate high in conscientiousness tended to be less creative, whereas extraversion, agreeableness, and openness were positively associated. (If you don’t check in with your boss throughout the day, just tell him or her it’s because you are a deeply creative soul.)

Meanwhile, researchers in Berlin have recently looked at the other side of the equation—how looking at art affects our emotions. “How does beauty feel?” asks the paper, published in the journal Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts.

We all know that art can provoke an intense response. As the researchers write, “The notion that aesthetic appeal is more felt than known has a substantial tradition in philosophical aesthetics. Emotions accompany and inform our experiences of art, literature, music, nature, or appealing sights, sounds, and trains of thought more generally.”

But until now, there has been no consensus about how to classify these emotional responses to art. The “Aesthetic Emotions Scale,” or AESTHEMOS, sets out to solve that. The new tool is a questionnaire that assesses 21 emotional reactions a person might have to a work of art, including enchantment, awe, wonder, boredom, or relaxation.

The AESTHEMOS developers say the tool can be used to determine precisely which attributes of an artwork give someone the “chills,” say, or how experts and laypeople experience art differently. It can also help determine how your personality type will inform your emotional response to an aesthetic experience.

And someday, maybe—just maybe—it can even help us understand why someone paid a half-billion dollars for a single painting.