Are we in the middle of a cultural building boom? More than 101 major arts facilities opened around the world last year, according to a new study. The construction of museums, performing arts venues, and cultural districts cost a combined $8.45 billion.

For more than two years, analysts at the firm AEA Consulting have been tracking announcements of new cultural projects on behalf of the Global Cultural Districts Network. (They get a lot of Google alerts, in several languages.) They have used the data to compile the Cultural Infrastructure Index, released today, which offers a rare snapshot of just how much money is actually being invested in the construction of arts buildings around the world.

Their findings also suggest that the reasons behind this boom are more complex than a simple love of the arts. “It’s not people banging on the doors saying, ‘We want more culture,’” says Adrian Ellis, the founder of AEA Consulting. “There are other things at play, like globalization and nation-building.”

The level of investment in cultural infrastructure is only likely to grow as time goes on. On top of the 101 projects completed last year to the tune of $8.45 billion, an additional 135 were announced, according to the index. The planned projects cost a combined $8.54 billion. (The team limited its search to projects with a budget of $10 million or more that were completed or announced within the 2016 calendar year.)

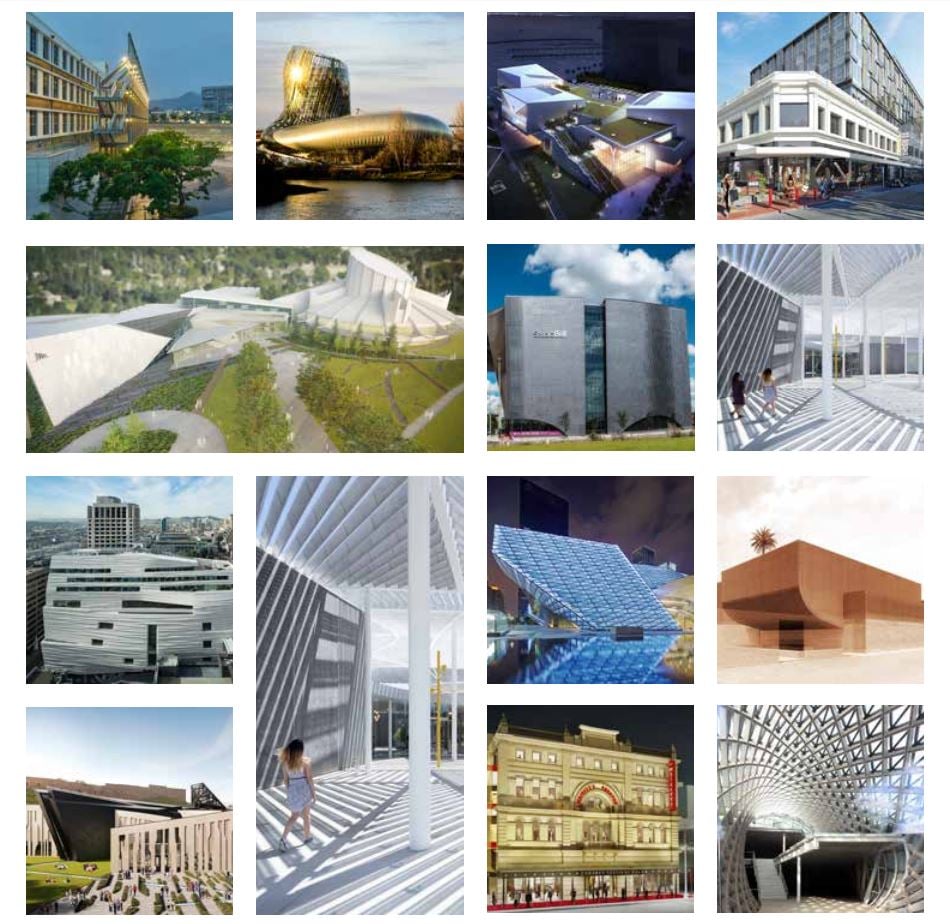

Cultural Infrastructure Index (2016), courtesy of the Global Cultural Districts Network.

Europe invested the most in yet-to-be-completed projects: $3.9 billion. North America came in second, with $2.1 billion worth of planned cultural investment. Asia came in third, with $1.3 billion. There was one big surprise: Australia and New Zealand edged out the Middle East for the fourth slot, having pledged $625 million to cultural construction last year.

“The level of investment is remarkable,” Ellis says of the ascendance of Australia and New Zealand. “For all its size, there aren’t that many people in those regions.” The driver behind the massive spend, he notes, is a push for tourism.

Cultural Infrastructure Index (2016), courtesy of the Global Cultural Districts Network.

The study also suggests that culture is only going to become more decentralized in the future. Projects in the 75 largest cities around the world accounted for just 31 percent of completed projects and 35 percent of announced projects. Ellis describes this as the “second city phenomenon.” Major culture-rich cities like New York and London are approaching a saturation point, while smaller destinations “are asserting that their time has come.”

The report also reveals that museums are the most popular form of cultural building project, far ahead of cultural districts or performing arts centers. An eyebrow-raising 89 museum initiatives were announced last year alone.

From an urban planning perspective, Ellis notes that museums have a significant leg up over performing arts institutions: “Museums are open during the day,” he notes. “With performing arts, you have to be there at 8 p.m. and leave at 10 p.m.”

Cultural Infrastructure Index (2016), courtesy of the Global Cultural Districts Network.

Ellis anticipates that the Cultural Infrastructure Index will become more sophisticated each year. Moving forward, researchers plan to add additional details, including each building’s architect, size, and organizing structure, i.e. whether it is private or nonprofit.

“I’m curious what happens to architecture as we enter a period of nationalization after a wave of globalism,” Ellis notes. “It will be interesting to see if there is a tendency toward a national or vernacular architecture.”

Despite the significant investment in cultural infrastructure, however, outside statistics put the expenditure in perspective. While more than $8.5 billion was spent last year on cultural construction, more than ten times that was spent on road construction in 2010—in the US alone.