MoMA Bashing Is In

What if you threw a preview party and nobody came?

While that might be a problem for most people, it could signal impending doom for Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) curator Klaus Biesenbach, a man who has been alternately called Herr Zeitgeist and the art world’s walker extraordinaire. According to a well-placed MoMA source, who spoke on the condition of anonymity for fear of reprisal, that is exactly what happened on March 3 at the trustees-only preview for the institution’s ill-conceived Björk retrospective: Board members expressed their dismay at the exhibition by overwhelmingly staying away.

According to that source, the closely monitored 6:00 p.m. vernissage let only MoMA trustees and their handpicked guests into the exhibition. Yet the preview for the eponymously named “Björk” show saw just two board members out of a possible 66 attend (that number does not include the museum’s additional 12 Honorary Trustees according to the museum’s website).

A colleague of Biesenbach’s in the art handling and preparation department posing with Bjork’s swan dress.

Photo: Instagram/@klausbiesenbach

At 8:00 p.m., after the doors opened for museum members, press, and sundry folks lured by Björk’s global celebrity, one of the trustees present was heard to remark acidly, “This looks like a nightclub in Ibiza.”

Despite the crowds lined up outside the museum to see Biesenbach’s newest addition to MoMA’s recent string of curatorial turkeys, discontent within the famously tight-lipped institution appears to have turned against the German curator.

The principal author of an exhibition that has been called, alternately, a “fiasco” (Jerry Saltz), an “abomination” (Deborah Solomon), and the show that turned “MoMA into Planet Hollywood” (Michael Miller), Biesenbach—the institution’s Übersocial, fame-obsessed, Chief Curator at Large—has seemingly finally come in for some in-house scrutiny. A growing consensus outside the institution says it’s about time. (See: Ladies and Gentlemen, the Björk Show at MoMA is Bad, Really Bad and The 6 Best Takedowns of MoMA’s Appalling Björk Show.)

The organizer of 16 separate MoMA exhibitions as well as more than 50 additional shows at MoMA PS1, where he holds the title of Director, Biesenbach has enjoyed widespread popularity since being named curator at MoMA in 2006. Yet he has received blisteringly bad press in recent weeks.

Besides the nearly universally negative headlines that have accompanied the “Björk” exhibition, questions have emerged lately about Biesenbach’s curatorial autonomy, his problematic celebrity profile, as well as his capacity to keep an appropriately scholarly distance between himself and his famous subjects—boldface names like Tilda Swinton, Antony Hegarty of Antony and the Johnsons, Marina Abramović, and, of course, Icelandic songstress Björk.

To make matters worse, these issues have rapidly percolated upwards to the office of MoMA’s Director, Glenn Lowry. With New York Magazine critic Saltz quoting, earlier this month, “long-time MoMA watchers” who find it incredible that the Director “has not been let go by the trustees,” and the influential website e-flux declaring days later “MoMA’s Björk problem is a leadership problem,” the unthinkable has happened to the once-hosannaed cathedral of modern art—MoMA-bashing is in.

Biesenbach Flying Solo

Several astute museum experts have said that MoMA’s curatorial departments are organized according to an old-timey structure, which people at the institution call the “Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs” scheme. According to a source, each of the museum’s departments is placed beneath the direct tutelage of Lowry, his Chief of Staff Diana Pulling, and Associate Director Kathy Halbreich.

These departments—Architecture and Design, Drawings and Prints, Film, Media and Performance Art, Photography, Curatorial Affairs, the Department of Painting and Sculpture, as well as Biesenbach’s own independent curatorial republic—are then allotted separate but unequal shares of resources, influence, and power. Headed up by curator Ann Temkin, the department of Painting and Sculpture has traditionally assumed the marquee billing of Snow White—until now, that is.

Sources inside the museum declare that Biesenbach’s free-floating curatorial brief has ballooned in such a way as to upset the museum’s traditional hierarchy; a process they say snowballed after the popular success of the 2010 show “Marina Abramović: The Artist Is Present.” These same sources indicate that Biesenbach’s fame-focused curatorial efforts have also become conspicuous at MoMA for escaping significant supervision.

A look at the museum’s organization shows that Biesenbach’s portfolio is unburdened by the presence of other curators—professionals who might execute or, alternately, question his decisions. It’s also widely rumored inside the institution that the Chief Curator at Large reports directly to Lowry’s office. In Disney fairy tale terms, Biesenbach is the new “Snow White”—with a desperate coolhunting twist.

We’ve created a chart of MoMA’s organization based on information obtained by artnet News. Employees subordinate to the directors of each department are represented by a simple person icon. Click through for a larger view.

©artnet News

Rumors about Biesenbach’s unprecedented autonomy suggest that he routinely bypasses Pulling and Halbreich on crucial decisions. This idea, in turn, helps explain the lack of curatorial oversight that has characterized some of Biesenbach’s more recent exhibitions.

How, for example, does one begin to explain the institutional relevance of the band Kraftwerk’s eight-gig show “Retrospective 12345678” staged inside the museum’s atrium in 2012? How, one might ask, do you account for the 2013 spectacle of actress Tilda Swinton sleeping inside a glass box at MoMA—an unacknowledged rip-off of conceptual artist Chris Burden’s four-decade old Bed Piece (1972)?

And what possible defense is there—leaving aside the weird trend-spotting logic involved in awarding a terminally passé musician valuable art historical real estate—for the unmitigated artistic and exhibition design disaster that is “Björk”?

When we asked who worked on the show with Biesenbach, we were told by MoMA personnel over email, “Klaus is listed as the sole curator of the exhibition in our materials: The exhibition is conceived and organized by Klaus Biesenbach, Chief Curator at Large at MoMA and Director of MoMA PS1.” We were also informed that he worked with two curatorial assistants.

MoMA insiders identify all three of these displays—alongside the museum’s commissioned concert and performance event Swanlights, a “meditation on light, nature, and femininity” by musicians Antony and the Johnsons with a 60-piece orchestra at Radio City Music Hall—as instances of unseemly celebrity chasing and gross curatorial overreach. Together with the growing number of gaffes committed by the German curator, such episodes would indicate that Biesenbach is mostly flying solo.

Once MoMA’s golden boy for the museum’s active engagement with 21st-century art, Biesenbach has also produced his share of over-the-top blunders. One important slip-up took place at what should have been a high point for the curator—during the dying moments of Abramović’s 2010 performance.

As recounted by anonymous sources, Biesenbach interrupted Abramović’s precisely-timed 736-hour-and-30-minute marathon action in order to bask in some of the artist’s accumulated megawatt company. Scheduled to endure the performer’s gaze for a quarter of an hour, the curator lasted just eight minutes.

After vacating the chair, applause followed; but it was obvious from Abramović’s expression that something had gone wrong. The problem: Biesenbach had cut the performance short by throwing off its strict time signature. As relayed to artnet News, Abramović was livid.

According to Artforum’s Linda Yablonsky, things quickly went from bad to mortifying at Abramović’s celebratory dinner. Writing in the “Scene & Herd” column, Yablonsky described the excruciating series of events that followed as “the tippling Biesenbach took the podium” to kick off of the evening:

He didn’t thank anyone. Instead he used the moment to make public his two-decade-long unrequited love for Abramović. ‘Look at me, Marina,’ he began. ‘Listen to me, Marina,’ he went on. ‘Why don’t you look at me? You know,’ he then said to the guests, tossing aside his prepared remarks, ‘she can’t see anyone without her glasses,’ thereby negating the experience of all those sitters who thought she was paying special attention to them. This brought loud murmurs… Recalling how he had fallen in love with Abramović, twenty years his senior, at first sight, he said that he believed she had fallen in love with him, too. ‘Biggest mistake of my career,’ he said.

Aghast at the spectacle, Yablonsky added her own lapidary rejoinder. “Though clearly, not bigger than this one,” she wrote, channeling the gathering’s dazed chagrin.

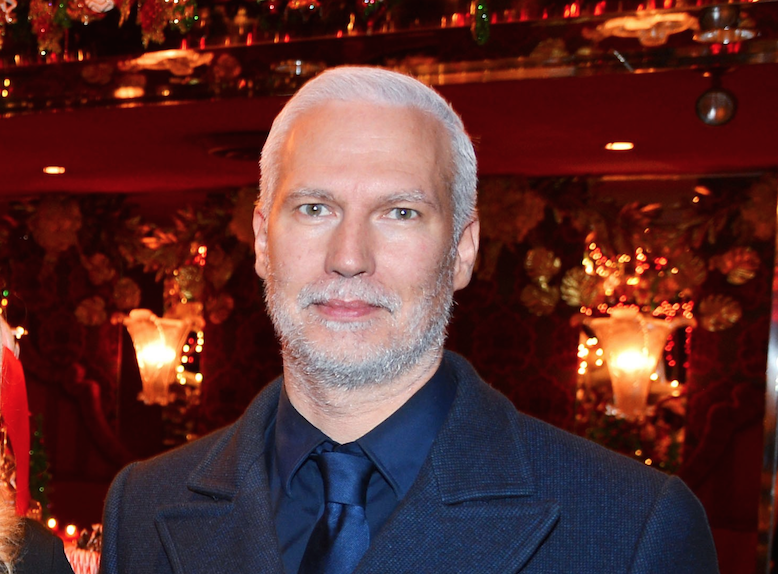

Biesenbach with Lady Gaga.

Photo: Instagram/@klausbiesenbach

The Art World’s Truman Capote

Besides being just plain embarrassing, Biesenbach’s behavior exemplifies what for many—both inside and outside the museum—constitutes the curator’s dangerous obsession with pop stars, as well as a growing compulsion to share in their limelight.

Biesenbach’s pronounced hobby of hanging out with famous people is no secret, since he documents these encounters endlessly on social media—sometimes multiple times a day. At Christmastime, for instance, Biesenbach posted Instagram photos of himself with Lady Gaga, Courtney Love, Abramović, and James Franco. The images appeared in Page Six within hours.

It has also become routine for Biensenbach to escort celebrities rather than artists or patrons to museum events. Among the long list of his red-carpet muses are Australian singer Kylie Minogue, Pablo Picasso’s granddaughter Diana Widmaier-Picasso, Sex and the City actress Kim Cattral, and fashion designers Hedi Slimane and Miuccia Prada. An art world Truman Capote, Biesenbach squires these VIPs around town like tabloid-worthy, masscult “swans.”

But Biesenbach’s wooing of entertainers and boldface names has also recently run afoul of the blowback police; younger tastemakers, that is, who get the strong impression that Biesenbach’s celebrity friendships answer to baser motives—among them, the curator’s own self-promotion and status-seeking.

Recently, Biesenbach’s groupie-like behavior was called out at a 2014 Art Basel Miami after-party. As reported by Artforum’s Sarah Nicole Prickett, the rapper and performance artist Mykki Blanco confronted Biesenbach at the event. Among Blanco’s accusations—shouted as the singer threw pieces of sandwich in the curator’s face—were that Biesenbach “doesn’t care about black people unless they’re famous,” that he merely hobnobs with big-time names like “Mickalene Thomas” and “Kehinde Wiley” instead of supporting black artists, and that the curator “doesn’t like black people, he likes black culture.”

Personal animus aside, Blanco has something of a point. Biesenbach’s exhibition record shows that he has organized only one solo outing by a black artist at MoMA and MoMA PS1 since 1996: “On-site 3,” a show by painter Mickalene Thomas.

Elsewhere, Biensenbach has also exhibited less than exemplary conduct when faced with situations that don’t immediately advance his tightly networked professional and social agenda. A recent instance of what might be termed the curator’s “positional conduct” concerns his puzzling lack of support for Cuban performance artist Tania Bruguera.

A globally famous figure with a well-known name, Bruguera was arrested in Cuba on December 30 this past year after attempting to enact a pro-democracy performance in Havana’s Revolutionary Square (see: How Tania Bruguera’s “Whisper” Became the Performance Heard Round the World). As documented by his social media footprint, Biesenbach followed Bruguera to Cuba to attend the artist’s aborted performance.

When news spread about the artist’s arrest, Biesenbach reportedly quailed. Sources told artnet News that Biesenbach packed his bags and fled Cuba rather than use his privileged position as a representative of one of the world’s most important art museums to pressure the regime to aid Bruguera (see: Why Is the Havana Biennial Afraid of Tania Bruguera).

Listing a location of “random island” Biesenbach wrote on Instagram “finally a lazy stupid tourist beach hour after such a week of worry and turmoil…tania will need a lot of support from the international art world to go through this further relatively unharmed.”

Photo: Instagram/@klausbiesenbach

After leaving Cuba, Biesenbach posted various entries to his Instagram account from another Caribbean country, possibly the Bahamas (social media is notoriously difficult to use in Cuba). One entry, which resembles a photo used to advertise Sandals Resorts, features a picture of crashing surf. It reads blithely: “finally a lazy stupid tourist beach hour after such a week of worry and turmoil…Tania will need a lot of support from the international art world to go through this further relatively unharmed.”

Alarmed at the curator’s lack of urgency, one of Biesenbach’s Instagram “followers,” using the social media handle “coriredstone,” implored the curator to act on his own counsel. “Klaus, you should do a media blitz ASAP,” she wrote with noticeable exasperation, “coordinate w Cuban expats and raise all hell or they may kick [Bruguera] out permanently or worse, lock her back up.”

Unfortunately, as of now, no sign of such a “media blitz” exists—this despite the fact that MoMA’s standard-bearer remains uniquely positioned to speak to Bruguera’s case as one of the few global figures who witnessed this watershed act of repression firsthand. (See: Cuban Officials Brand Tania Bruguera a Criminal.)

While it’s certainly important that the Guggenheim and MoMA have both come out in support of the dropping of charges against Bruguera, Biesenbach continues to pass up a golden opportunity to exercise his considerable influence to benefit art’s most essential value—freedom of speech.

Biesenbach with Bjork.

Photo: Instagram/@klausbiesenbach

Body-Snatching the Place of Bona Fide Artists

To his everlasting credit, Biesenbach became well know in 2012 for having coordinated substantial relief efforts for communities affected by Hurricane Sandy, especially those located near his second home in the Rockaways. For this, the curator drafted an open letter to Mayor Michael Bloomberg and fellow New Yorkers, and turned MoMA PS1 into a temporary shelter for displaced residents.

As one might expect, Biesenbach’s letter was signed by a laundry list of A-listers, including Madonna, Lady Gaga, Gwyneth Paltrow, and Franco. A moment when Klaus and his swans demonstrated that they were capable of more than arty glitz and counterfeit vanguardism, the episode demonstrates a tried and true way well-known entertainers can join lesser-known art world types to achieve important goals. (See: Patti Smith’s Resilience of the Dreamer Celebrates the Rockaways.)

As Choire Sicha wrote in 2012 for Bookforum in a canny piece about Biesenbach’s thorny adulation of celebrity, “Actors and singers (sometimes even dancers) are, on the whole, more famous than actually of quality.” This, Sicha says, has been the reason that the performing arts have always had “an uncomfortable relationship with the higher-end curatorial ambitions of the museum.” But Biesenbach’s promotion of celebrity and social media buzz at MoMA has effectively turned the old relationship between the museum and pop stardom on its ear.

With Biesenbach’s latest critical debacle, the logic of the new no-brow museum has suddenly become crystal clear. At today’s MoMA entertainers with aspirations to high culture—Björk, Swinton, Hegarty, Franco, et al—have body-snatched the role of bona fide artists (see: Why James Franco’s Cindy Sherman Homage at Pace Is Not Just Bad, It’s Offensive). Despite former board President Agnes Gund’s warning—she told the New York Times last April, “There are a number of us on the board who don’t want to see the museum become a mere entertainment center”—MoMA has taken its crowd-pleasing to carnival extremes. Under such circumstances, who can blame board members and museum staff for being troubled by or outright deploring Biesenbach’s starfucking curatorial regime.

Recent reports from sources inside MoMA indicate that the attendance numbers for “Björk” are disappointing based on museum projections. (MoMA’s response to artnet News queries is that the museum “does not release mid-run attendance figures,” and that it has “reached capacity” for one component of the cramped exhibition, while wrangling “consistent but manageable queues” for the show’s other two installations.) If true, flagging attendance for this spectacularly bad show suggests that a corner may have been turned—there’s only so much negative press MoMA can receive without it impacting their gate. This bodes badly for Biesenbach’s next commemoration of celebrity culture, “Yoko Ono: One Woman Show, 1960–1971,” scheduled to open in May (see: Yoko Ono to Have Solo Show at MoMA in 2015).

Yet the museum’s secretiveness also points to how difficult it is to read—or write about—an immensely powerful institution that protects its own and circles the wagons at the least sign of a perceived threat or schism.

When artnet News reached out to Biesenbach and the museum for comment on the relentless criticism “Björk” has received, the curator declined to comment—an attitude very much in keeping with the institution’s imperious style.

And so it goes at the world’s most important museum of modern art. As one anonymous source told us: “Lots of trustees are unhappy with Biesenbach right now, but breaking ranks is a big deal. Change will come about only when the trustees who are in dissent get enough ammo to make their will explicit.”

On the heels of what many critics argue is the worst MoMA exhibition of all time, no moment seems more propitious for a change than now.