THE DAILY PIC (#1382): I think it’s almost always a mistake to look at Andy Warhol in aesthetic terms. (Although that’s what the art market seems to prefer). After all, Warhol’s earliest and greatest Pop works were first understood – pretty much correctly – as utterly un- or even anti-esthetic. He got his first and greatest charge out of rewriting and undoing the old rules of art, and I think it was an effect he was always looking to return to.

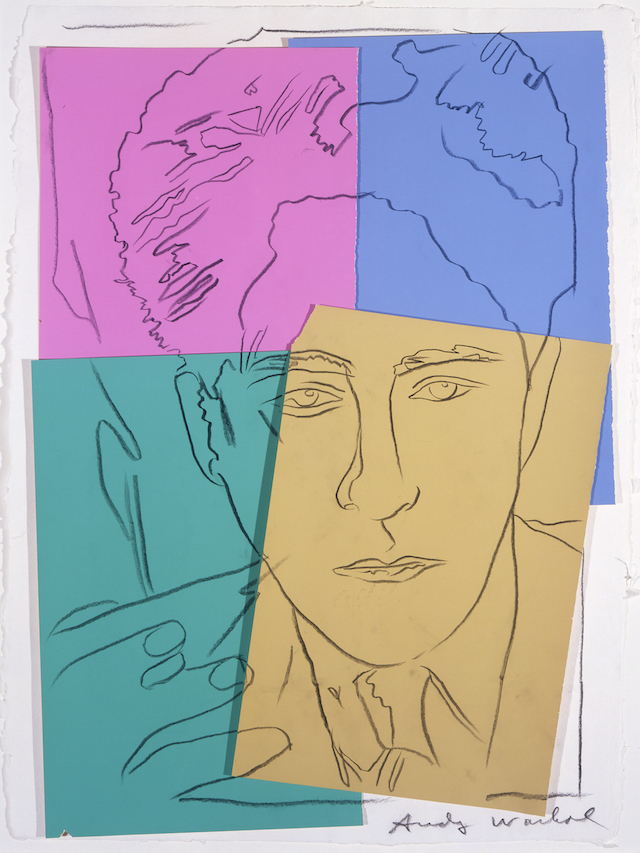

This 1983 piece is among the “The Late Drawings of Andy Warhol” now on view at the Hyde Collection in Glens Falls, New York. Aesthetically, it is pretty much business-as-usual for early 1980s graphic art – nothing to win Warhol much praise as an innovator. It only starts to matter when you think of it as a carrier of its subject matter, which you could say is made all the more transparently available given the banality of the carrier. That is, you “look through” the fairly standard, decorative image to get at what it shows. And what it shows, in this case, is the great French writer and filmmaker Jean Cocteau, who was 20-years dead when Warhol portrayed him. (The image is based on an old portrait shot, used on the cover of a 1983 book). Cocteau was one of the greatest radicals in 20th-century culture, and one of Warhol’s most openly gay predecessors. Who could have been more central to him?

Warhol’s biography provides a drumbeat of little-known Cocteau moments. In his last term in high school, in Pittsburgh, he would have gone to the nearby Outlines gallery to see Cocteau’s film “The Blood of a Poet” as well as a “concert” performance of Cocteau’s play “Orpheus”. At college, they screened Cocteau’s “Beauty and the Beast”.

In New York in 1950, when “Orpheus” appeared as a film, Warhol and some roommates were Cocteau-mad. Two years later, the drawings in Warhol’s first solo show, which were dedicated to the gay writer Truman Capote, were compared by a critic to Jean Cocteau’s. This was both an accurate account of their look and a euphemistic warning to readers about the precise nature of the “carefully studied perversity” they could expect to find in the show.

In 1959, when he’s about to launch into his Pop Art career, Warhol does the sets for a student production of “Orpheus” at Barnard College, sprinkling them with cut-outs of penises (which of course get censored at once).

And then, at the very other end of Warhol’s life, he brings Cocteau’s diaries to the hospital bed where he dies. The auction of his effects, at Sotheby’s in 1988, turns out to be full of Cocteau first editions that he’d collected.

So once again, it turns out that a piece of Warhol’s late, “light” work, which on aesthetic grounds we might want to dismiss, is in fact heavily freighted with significance – for Warhol and the culture at large.

One final thought: The main part of the face in today’s Pic, born by the beige sheet of paper, carefully crops out Cocteau’s trademark ‘fro and concentrates instead on his peculiarly bulbous nose. Does it turn the Frenchman into the balding, bulbous-nosed youth who first sat through Cocteau’s films in Pittsburgh? (The Andy Warhol Museum Pittsburgh; Founding Collection, Contribution The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. © 2015 ADAGP, Paris, / Avec l’aimable autorisation de M. Pierre Bergé, président du Comité Jean Cocteau; image © The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.)

For a full survey of past Daily Pics visit blakegopnik.com/archive.