To exhibition-goers and culture lovers, “Life is Architecture” at M+ in Hong Kong has been nothing but a treat since it opened in late June. The show, billed as the first major retrospective of Chinese-American architect I. M. Pei (1917–2019), offers a rare opportunity to revisit the iconic buildings and high-profile projects he built around the world that made him one of the most influential architects of the 20th and 21st centuries.

To architects, the exhibition on Pei carries an extra layer of meaning. It is not just about one big name, but it offers the audience a glimpse of what the practice of architecture is about, according to architect Betty Ng.

Installation view of I. M. Pei: Life Is Architecture, 2024. Photo: Wilson Lam

Image courtesy of M+, Hong Kong.

“Despite that the exhibition is billed as a retrospective of Pei, his work is exhibited and curated as a body of work that involves a vast amount of collaborators, ranging from his clients to glass manufacturers and artists. Among my favorites are the illustrations by Helmut Jacoby, who also collaborated with Norman Foster,” noted Ng, who is the founder and director of the Hong Kong headquartered firm Collective, which has worked on architecture and exhibition design projects across the region and beyond, including Christie’s new Asia headquarters.

The “refreshing” approach shows “how architecture is done through a coherent understanding across various parties, which is a reality in practice but not well understood by outsiders,” she said.

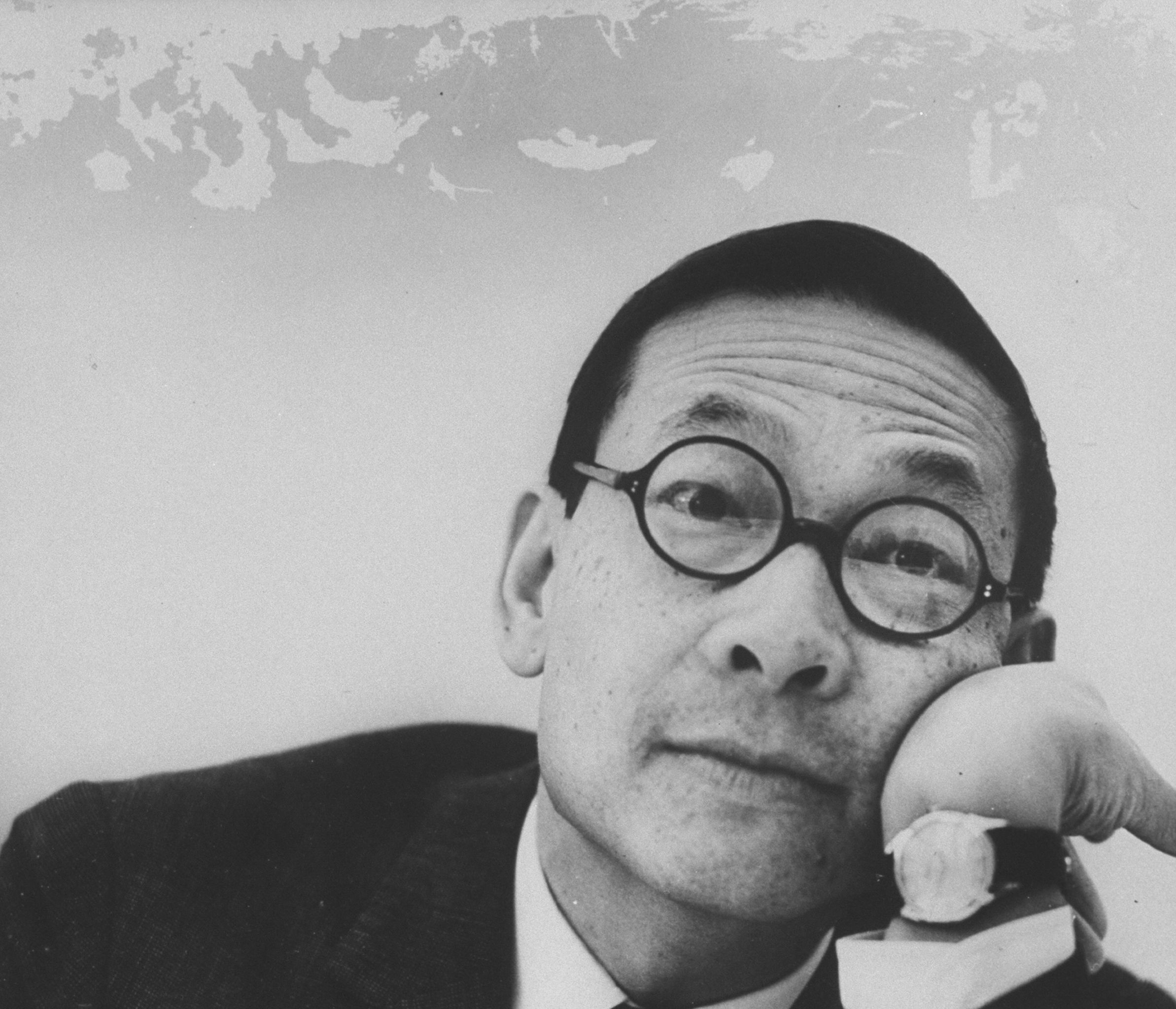

Peter Rosen,

First Person Singular: I. M. Pei (1997). Image courtesy of the director.

The Pritzker Prize-winning architect I.M. Pei, whose full name is leoh Ming Pei, may be best remembered for the National Gallery of Art East Building in Washington, D.C., as well as the Louvre Pyramid, which went from being one of the most hated proposals during the museum’s renovation to an iconic piece of contemporary architecture in Paris. Other major projects are the Bank of China Tower, which challenged the public’s perception of architecture in Hong Kong and the Museum of Islamic Art in Doha, the latter of which he built at the age of 91. Despite his institutional might, Pei did not get a museum retrospective until now.

Curated by Shirley Surya, design and architecture curator at M+, and Aric Chen, general and artistic director of Nieuwe Instituut (New Institute) in Rotterdam and formerly M+’s founding lead curator for design and architecture, the show was organized with the support of the Estate of I. M. Pei and Pei Cobb Freed & Partners has been seven years in the making.

Installation view of I. M. Pei: Life Is Architecture, 2024. Photo: Dan Leung. Image courtesy of M+, Hong Kong

The exhibition tells the story of Pei’s life and practice through six chapters and it features more than 400 objects, with many being shown for the first time.

“It’s hard to pick ‘favorites’ as each exhibit—be it a video, a letter, model, or drawing—is key in revealing certain aspects within each thematic section of the exhibition,” said exhibition curator Surya. While attention is likely drawn to some of Pei’s landmark designs, Surya noted that as a historian, she was grateful to have found several lesser-known exhibits that demonstrated Pei’s versatility not just as an architect but also for his transcultural vision.

Installation view of I. M. Pei: Life Is Architecture, 2024. Photo: Lok Cheng. Image courtesy of M+, Hong Kong

Among them is a series of short documentaries about Pei from 1970 that were kept at Pei Cobb Freed’s archive. It “revealed Pei’s articulate and reflective stance on his practice and presented him as an important public figure even before accomplishing other projects later,” the curator pointed out.

The other is the model of Taiwan Pavilion at Expo 1970 in Osaka. The model on view was built in collaboration with master’s students at the Chinese University of Hong Kong’s School of Architecture, which also served as the exhibition’s dedicated model maker.

I.M. Pei’s Bankers’ club drawing from undergrad project at MIT. Photo: M+.

“As a temporary structure, few knew of Pei’s involvement in this project. But its design for a circuitous exhibition path—through two multi-story triangular volumes with multiple bridges—akin to the unfolding sequence of spaces experienced while walking through a Chinese garden really demonstrated Pei’s ability to reinterpret culturally specific historical archetypes for the design of a contemporary and modern structure,” said Surya.

The I.M. Pei designed Suzhou Museum opened in 2006. Photo: M+.

Architect Ng, who also teaches architecture at the Chinese University of Hong Kong with her Collective directors Juan Minguez and Chi Yan Chan as a collective teaching cohort, was the team behind this education engagement. Students were asked to conduct in-depth research of two of Pei’s culture-related projects: a Museum of Chinese Art for Shanghai in 1948, an unrealized proposal that was originally Pei’s Harvard Graduate School of Design thesis, and Taiwan pavilion at Expo ’70 in Osaka. These aspiring architects were asked to reflect on the idea of “Chineseness” through Pei’s work. Ng and her teammates found this exercise inspiring.

“To us, as architects from different places practising in the context of Asia, we have always been asked to create ‘a design with Asianess’. There is no straight forward answer to this delicate matter, but the collaboration was a great exercise to explore various design methodologies through the understanding of characters instead of motifs,” said Ng.

Liu Heung Shing, I. M. Pei with Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis and guests at Fragrant Hill Hotel’s opening (1982). Photo: © Liu Heung Shing

The show also highlights the backdrop of important historical moments throughout the decades of Pei’s career that saw key cultural and geopolitical transformations across the world. Important archival images on view include those depicting Pei’s interaction with important figures such as French-Chinese artist Zao Wou-Ki and Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis, and scenes representing the modernization of China.

To Ng, projects that Pei had worked on with real estate tycoon William Zeckendorf being showcased alongside other arts and cultural projects was moving. The collaboration gave Pei a reputation of being “an architect for a developer.” Reflecting on this, Ng noted that private developers play a more dominant role in the architecture ecology in Hong Kong and the region, compared to Europe, where she had worked before. By putting these commercial projects on view, it helped to clarify the basis of architecture design, which is about methodology, rather than genres and styles. “We do not believe in being a particular type of architect. We believe in architecture,” she said.

Marc Riboud, I. M. Pei and Zao Wou-Ki in the Jardin des Tuileries in Paris ca.1990 © Marc Riboud/Fonds Marc Riboud au MNAAG/Magnum Photos

The exhibition will run until January 5, 2025. But in case one isn’t able to make a trip to Hong Kong for the show, don’t fret. There may be a chance to see the show elsewhere afterwards. “We are currently in various discussions to bring this exhibition to a wider audience in different parts of the world,” Surya noted.