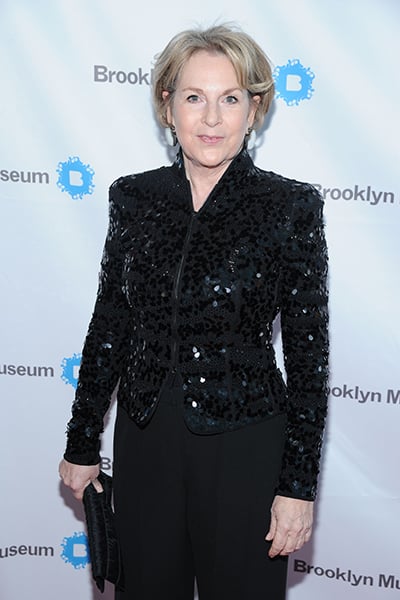

How should we describe women who are major art collectors and supporters of art institutions and initiatives? If Brooklyn Museum chairwoman Elizabeth Sackler has her way, it won’t be “patron of the arts.” The arts activist and public historian has long held that “matron” should be the default female counterpart to the more widely used “patron.” And lately, she’s been giving a number of institutions a gentle nudge towards officially adopting the term. Though she’s not about to launch an official crusade, Sackler hopes more institutions will join the burgeoning matron movement.

For Sackler, adding the phrase “matron of the arts” to the art world lexicon is only appropriate, given the important role women play in funding, strengthening, and promoting the arts. While there has been a long history of influential women in the arts including Marie de’ Medici, Peggy Guggenheim, Agnes Gund, Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney, and Isabella Stewart Gardner, Sackler notes that patrons are automatically assumed to be men, not women.

“This has to do with acknowledging what has happened to the language—that patron elevates men and matron denigrates women,” she told artnet News. Though the term may evoke spinsterhood for some, Sackler sees such negative connotations as cultural construct that has nothing to do with the real linguistics. “There’s an imbalance there. I don’t consider this a feminist alternative, but the correct descriptor insuring that the women who have and do support artists . . . are recognized as women.”

The distinction between the two terms became clear to Sackler when the Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art opened at the Brooklyn Museum in 2007. “When I was being interviewed for the opening of the Sackler wing, it was instinctive,” she explained. “I said, ‘No, I’m not a patron; I’m a matron of the arts.'”

The Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art.

Photo: Courtesy of The Brooklyn Museum

The issue came into play again this year, when she was named the institution’s first female chairwoman after many years spent serving on its board (see “Elizabeth Sackler Named Brooklyn Museum’s First Chairwoman“), and when the US pavilion for the upcoming Venice Biennale sent her an email that detailed their donor levels, one of which was “patron.”

The US pavilion is just one of several institutions that, at Sackler’s urging, has expanded its glossary, recognizing matrons alongside patrons as donors. Florence’s Studio Art Centers International, Brooklyn’s Groundswell Community Mural Project, the Professional Organization of Women in the Arts, New York’s Women’s eNews, and the National Museum of Women in the Arts in Washington, D.C., have all made the change, and four other major institutions are considering following suit. Intriguingly, New York’s El Museo del Barrio was already a step ahead, recognizing both madrinas and padrinos among its members.

Sackler is quick to clarify that promoting arts matrons is hardly a full-time gig—”there is plenty to keep me busy in Brooklyn,” she said. But when the issue comes up, she is always ready to raise awareness. Most people, she says, have never given the blanket application of “patron” much thought.

“People don’t stop to think about what the implications are for women in that women aren’t being recognized for their accomplishments in their own right, but are quick to agree that they should be.” She believes that matronage is the way of the future, and that “for the generations coming up, it’s going to make a big difference to their own sense of self and self recognition.”

“It’s not just semantics. It’s power,” Sackler concluded. “Words have power, and it’s important that we’re accurate with them, and careful, and pay homage and give gratitude to those women who support our institutions.”