A couple of years ago, Egyptian archaeologists excavating a necropolis south of Cairo discovered a papyrus marked with ancient Greek. Analysis eventually showed it bore Euripides’s Ino and Polyidos, two lost works, previously known only by hazy plot summaries and quoted snippets. Of the 5th-century B.C.E. playwright’s estimated 90 works only 19 survive, making the discovery among the most considerable contributions to Greek literature in half a century.

The achievement will be dwarfed if progress continues to be made on the Herculaneum scrolls, a collection of 1,800 texts that were carbonized into lumps by the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in in 79 C.E. It’s a potential gold mine of writings currently absent from the classical canon and a Silicon Valley-backed competition is pushing machine learning and computer vision enthusiasts to train their focus on virtually unwrapping the texts.

The thrill, in both cases, is of a past rendered ever-so-slightly richer by the discovery of things believed lost. But what of the countless other lost, disappeared, and abandoned books? What might literature (and the world perhaps) be like if it included Homer’s lost comedy Margites or the Bible still contained the Book of the Battles of Yahweh? What might it be like to stand in a room of these books? These are among the historical counterfactuals explored in an upcoming exhibition at New York’s Grolier Club, America’s oldest society for bibliophiles.

George Gordon Noel, Lord Byron. Byron’s Memoirs. Unpublished manuscript. Photo: Reid Byers/Grolier Club.

Set to run from December through February 2025, club member Reid Byers has been handed the curatorial keys for “Imaginary Books: Lost, Unfinished, and Fictive Works Found Only in Other Books.” It’s the grand extension of a thought experiment Byers has been toying with for some time and arrives courtesy of thorough collaborations with printers, bookbinders, artists, and calligraphers.

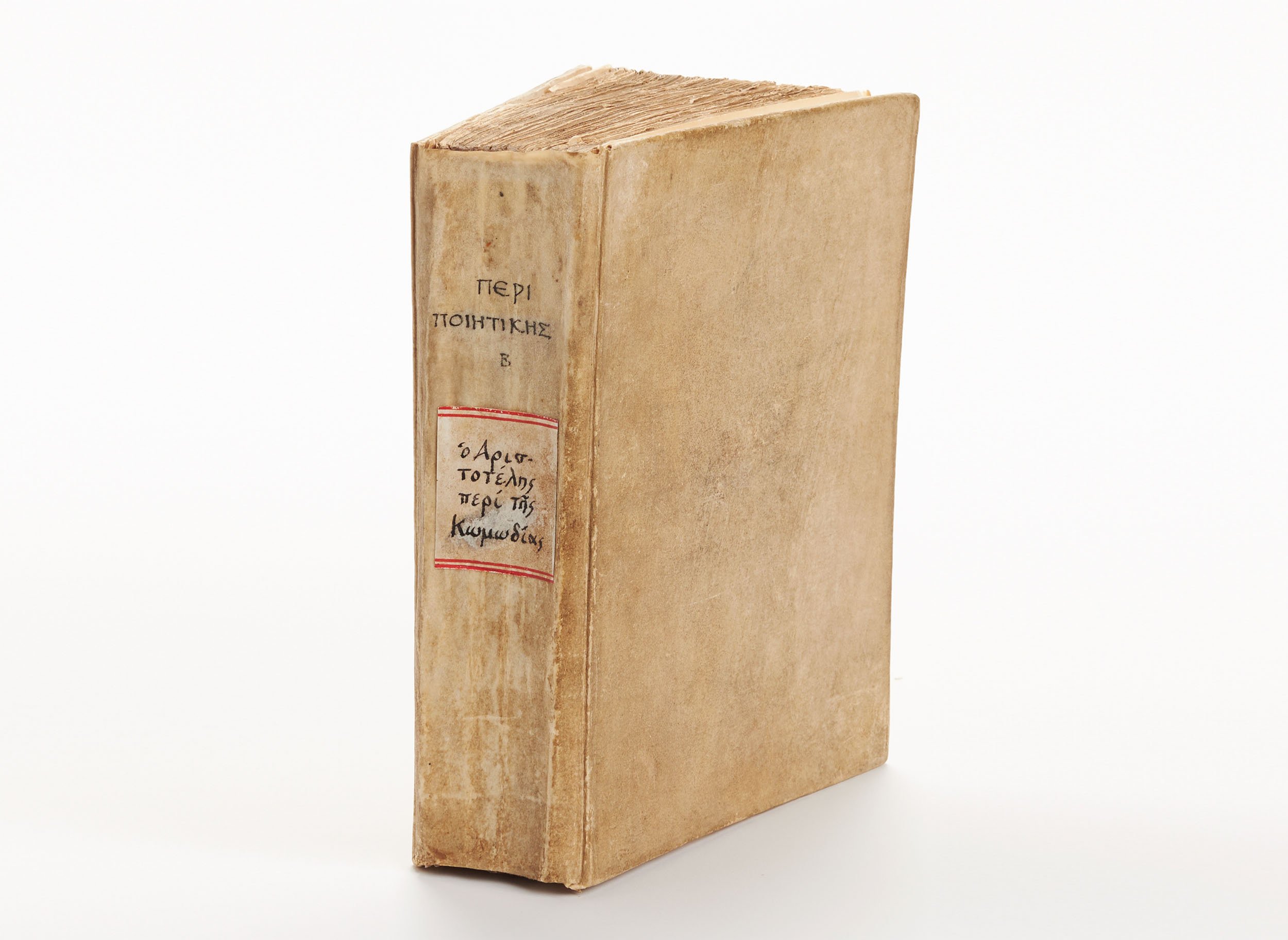

Byers has given life to more than 100 books and will spread them around the Grolier’s cozy second floor gallery. It is, the organizers admit, part conceptual art project and part literary indulgence. Visitors are asked to judge works entirely by their covers and, in so doing, dream up the stories and characters that these the unknowable books might hold inside. In turn, we find ourselves considering the first words and keystrokes for the books we know and love.

Abdul Al-Hazred, Necronomicon. In Vinegia: Appresso Gabriel Giolito de Ferrari et Fratelli, 1541. Anthropegal grimoire. Photo: Reid Byers/Grolier Club.

“An encounter with an imaginary book brings us forcibly to a liminal moment, confronted with an object that we know does not exist, but then it leaves us suspended in this strange space,” Byers said in a statement. “Every book in the world was an imaginary book when it was first begun to be written.”

Byers has devised three broad criteria for “Imaginary Books.” The first, Lost Books, counts among its number William Shakespeare’s Love’s Labours Won, the vanished complement to Love’s Labour’s Lost; Ernest Hemmingway’s first novel that was stolen from his wife (along with its carbon copies) in Paris; and Lord Byron’s tell-all memoir that was deemed worthy of burning by his publisher in 1824.

Sylvia Plath, Double Exposure (1962). London: Heineman, 1964. Manuscript disappeared c. 1970. Photo courtesy of the Grolier Club.

The second, Unfinished Books, presents works that were started but never finished or published. This includes Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s opium inspired reverie Kubla Khan, Sylvia Plath’s autobiographical Double Exposure that Ted Hughes allegedly prevented being published, and Raymond Chandler’s Shakespeare in Baby Talk.

Last are Byers’ Fictive Books, which emerge from the pages of fiction to find physical form at the Grolier Club. Chief among which is The Necronomicon the toxic, forbidden tome from H.P. Lovecraft’s writings. As is canon, it appeared locked away in a heavy-set safe. You can look and speculate but, as Byers said, “the book is not to be touched.”