Success arrived belatedly for generative art pioneer Vera Molnár: a major retrospective now on view opened a mere two months after her death.

It was Paris’s Centre Pompidou that broke the news on X in December with a message that read, “It is with deep emotion that we learn of the death of Vera Molnár, with whom we had worked passionately for her next major exhibition.”

That show, “Speak to the Eye,” now occupies the fourth floor of the Pompidou and offers a comprehensive look at an artist who seemed forever ahead of the curve.

To gauge Molnár’s art world standing today, look no further than the tributes that followed her passing. Aside from institutions, curators, and critics, prominent digital artists, and NFT platforms chimed in to herald the impact of her algorithmic experiments, or “Machine Imaginaire,” as she called them.

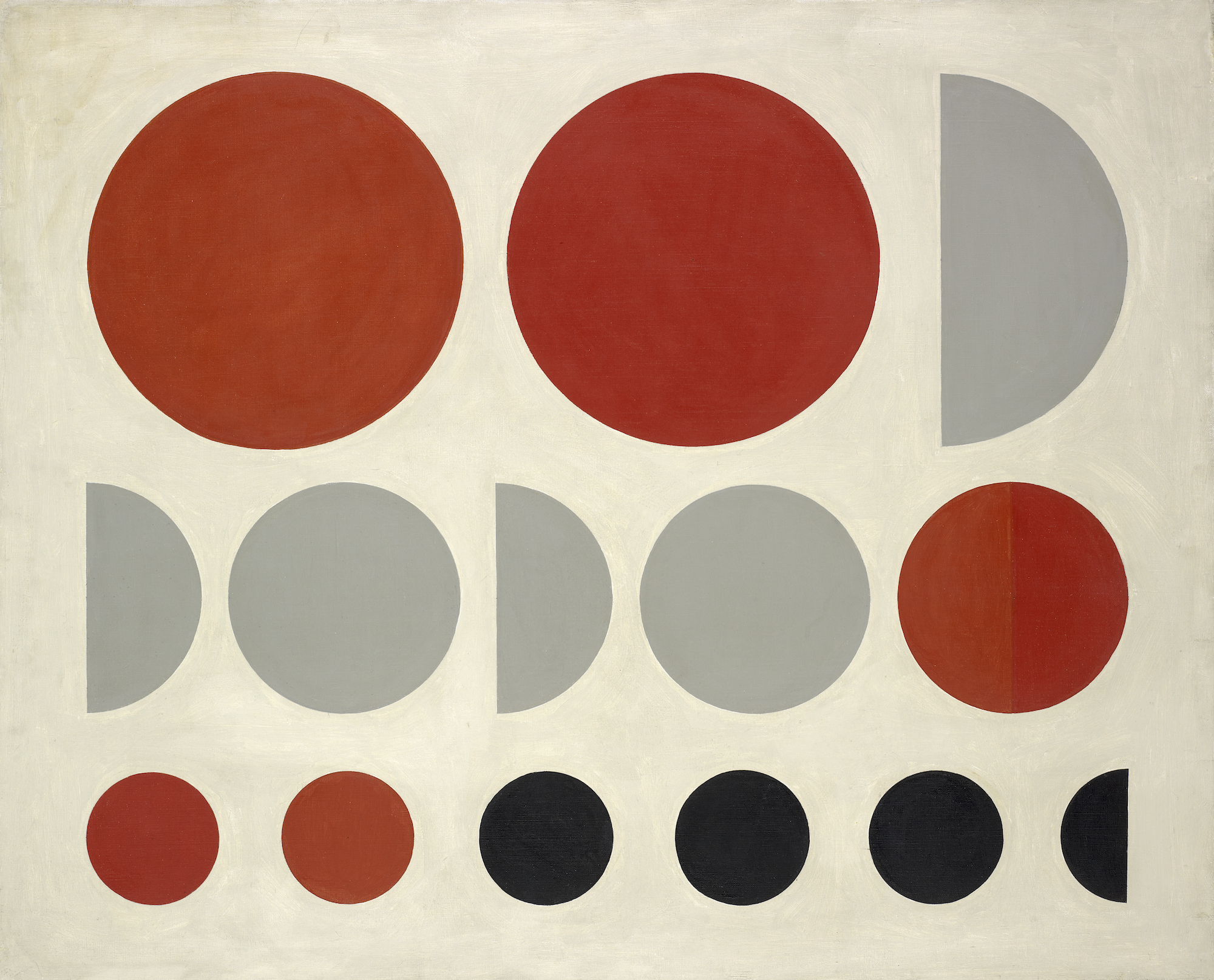

Vera Molnár, Four Randomly Distributed Elements (1959). Photo: Georges Meguerditchian Centre Pompidou.

Born in Budapest, Hungary, in 1924, Molnár studied art history at the Hungarian University of Fine Arts. She would later say that her first impactful encounter with art came through the pastoral paintings of her uncle. This influence is evident in the earliest works presented in “Speak to the Eye,” a collection of drawings from 1946 that present landscapes as geometric abstractions.

A year later, Molnár moved to Paris with her husband and sometime collaborator, the scientist François Molnár. There she fell in with a crowd of abstract artists that included Fernand Léger and Victor Vasarely, who pushed her geometric inclinations further. Works such as Circles and Half Circles (1953) and Four Randomly Distributed Elements (1959) speak to her contributions to the post-war geometric abstraction movement.

But the concept that would come to guide Molnár’s practice and shape her legacy was the “Machine Imaginaire.” Beginning in 1959, she used simple algorithms to inform the placement of lines and shapes. At the time, computers were elephantine, academic, screen-less things, and for nearly a decade she worked on grid paper by hand.

In 1968, Molnár talked her way into gaining access to a computer at the Sorbonne. She duly taught herself early programming languages such as Basic and Fortran and began producing work using punch cards and a plotter printer. This period is captured at the Pompidou in works such as A Stroll Between Order and Chaos (1975) and 160 Squares Pushed to the Limit (1976).

Installation view of “Speak to the Eye” at Centre Pompidou. Photo: Janeth Rodriguez-Garcia/Centre Pompidou.

This may be the breakthrough for which Molnár is best known, but “Speak to the Eye” offers an artist whose oeuvre is broader.

There’s sculpture in the form of Perspective on a Line (2014-2019), a site-specific installation that contorts exhibition walls, and a photographic series of sand and shadows from the 2000s.

Thrown in for good measure are 22 of Molnár’s diaries, filled with jottings and photographs and plans for upcoming works. She once said in interview that her whole life was squares, triangles, and lines. These diaries prove the point.

See images of works in the show below.

Vera Molnár, Icon (1964). Photo: Bertrand Prévost / Centre Pompidou.

Vera Molnár, Same But Different (2010). Photo: Philippe Migeat / Centre Pompidou.

Installation view of “Speak to the Eye” at Centre Pompidou. Photo: Janeth Rodriguez-Garcia/Centre Pompidou.

Vera Molnár, “In Search of Paul Klee”, 1970. Photo: Hervé Beurel.

“Speak to the Eye” is on view at Centre Pompidou, Place Georges-Pompidou, 75004 Paris, France, through August 26.