The heirs of a Jewish collector are lodging an appeal against the Dutch Restitutions Commission’s decision to allow the Stedelijk Museum to keep a Wassily Kandinsky painting in its collection.

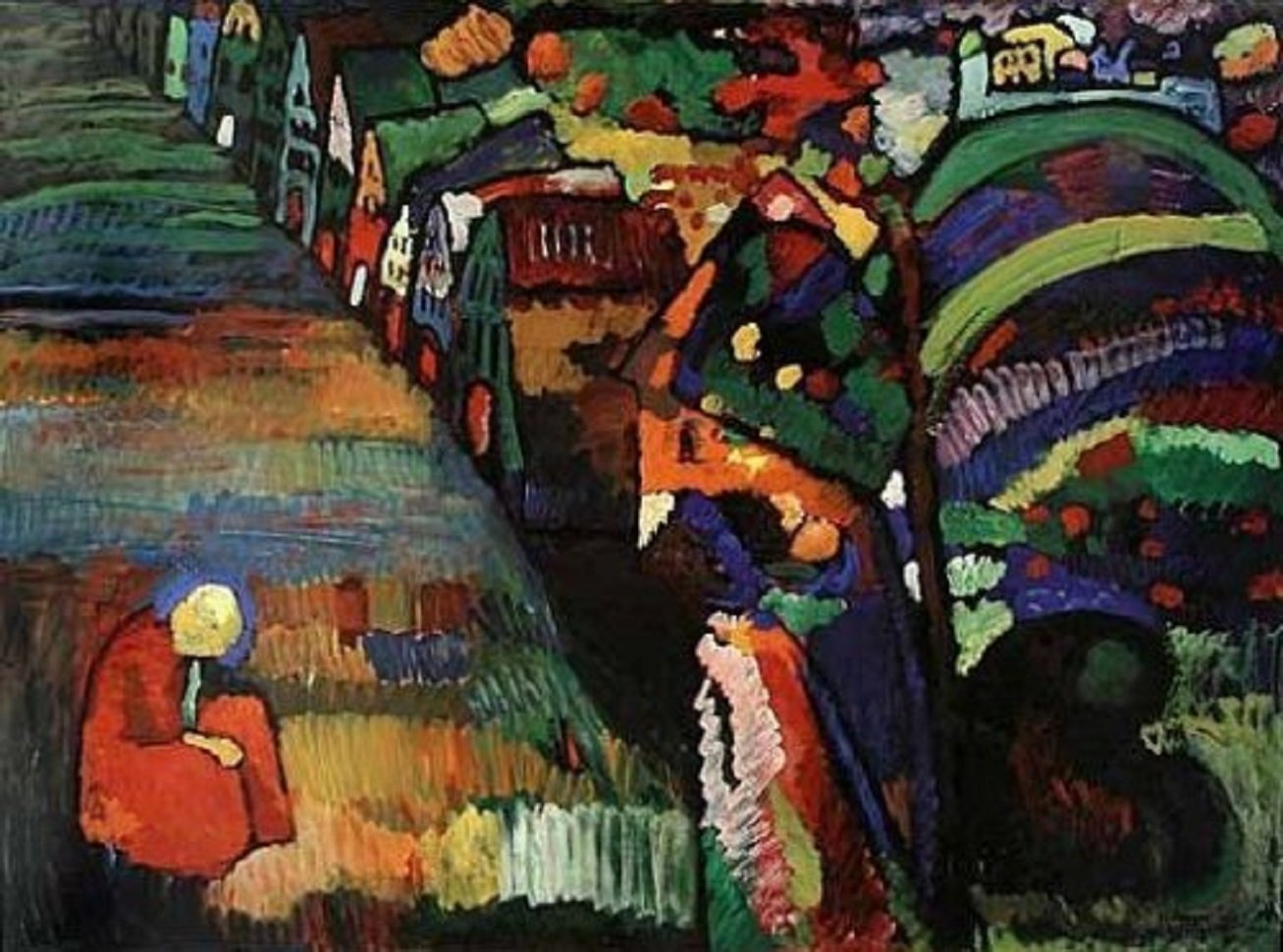

The museum acquired the work, a 1909 landscape painting titled Bild mit Häuser, from a Jewish collection in 1940, during World War II. The heirs of collector Robert Lewenstein and his wife Irma Klein came together to make an application for the painting, which the Dutch Restitution Committee denied in 2018.

The commission said that it had balanced the interests between the Lewenstein heirs and the Stedelijk Museum and found that the work should stay in the museum’s collection because the heirs had “no special bond with it,” and the work has a “significant place” in the Dutch collection.

It also said that the sale was informed by “deteriorating financial circumstances in which Lewenstein and Klein found themselves well before the German invasion.” The painting is in the Stedelijk collection, but is owned by the Amsterdam City Council. The commission noted that, after the war, Klein made no attempt to retrieve the work.

Some officials have called the commission’s decision unjust. Last month, the mayor of Amsterdam, Femke Halsema, issued a letter urging an official reconsideration of whether the Stedelijk Museum should rightfully hold on to the painting.

“It’s now been more than a month [and] we have heard nothing further from the city,” said James Palmer, founder of Mondex Corporation, which works on restitution cases. He represent the Lewenstein family alongside their lawyer, Axel Hagedorn.

In December, a committee assembled by the Dutch Ministry of Culture to reevaluate the situation found that the Dutch Restitutions Commission’s policy of considering a balance of interests between the claimant of a work and its current possessor is unjust and not in line with the 1998 Washington Principles on Nazi-Confiscated Art.

Following the committee’s findings, two members from the commission resigned, including its chairman.

Palmer said in a statement that he said he does not want the decision to go back to the commission, as the mayor has suggested. “Now that the weighing of interests in favor of the Stedelijk Museum has been abandoned, the painting should be returned,” he said. A reassessment by the commission would be “superfluous,” he added, and “grossly unfair to the claimants who have already endured almost a decade of trials and tribulations to bring this case to where it is today.”

The mayor’s office said it still supports a reassessment by the Restitutions Commission, telling Artnet News in an email that “a new assessment framework is currently being established.”

The claim for the painting was made in part by two grandchildren of the late Jewish businessman and collector Emanuel Lewenstein, who is the father of Robert Lewinstein. The heirs, who are based in the US, say they hope to split the painting’s value: 37.5 percent to each child, and 25 percent to Klein’s next of kin.

The Stedelijk did not immediately responded to a request for comment.

Palmer said he was “surprised” that the Dutch government was forging ahead with new policy on colonial era restitution, which includes a €4.5 million in funding for research on colonial artifacts, “instead of first dealing with property looted during the Second World War.”