Jim Jarmusch is known for his deadpan films that feature oddball characters and ask big existential questions. Among his best-known works in this vein are Stranger than Paradise (1984), a black-and-white minimalist comedy with a cult following, and Ghost Dog: The Way of the Samurai (1999), the tale of a principled hitman and pigeon keeper who finds himself marked by the mafia. His cinematography also often employs surreal storytelling devices, such as the trail of pink objects in Broken Flowers (2005) that reveals important character-defining clues throughout the movie but offers little in the way of plot resolution.

Given the quiet absurdism of many of his films, it comes as no surprise that the American director has a long-standing affinity for Surrealism. “The beauty of Surrealism is looking at things in a different way,” Jarmusch said. “It’s about juxtaposing the mundane and fantastical.”

Jim Jarmusch. Photo: Laurent KOFFEL/Gamma-Rapho via Getty Images.

As a teenager, Surrealism was a “revelation” to the burgeoning director, first in its visual forms and then its literary ones. In his early twenties, it drew him to Paris, “where I repeatedly used [André] Breton’s “Nadja” as a kind of walking map through the mysterious nocturnal streets of the city,” he said.

Jarmusch returns to Paris this week for Paris Photo, where he has curated a selection of 34 photos at the fair to celebrate the centenary of the Surrealism movement. His picks, Jarmusch added, are not purely Surrealist, but “reflect its tenets of the transformation of the ordinary into the dreamlike, and at times vice-versa.”

Peter Hujar, Catacomb Palermo (1963). ©Peter Hujar Archive, LLC; Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY. Courtesy Stephen Daiter

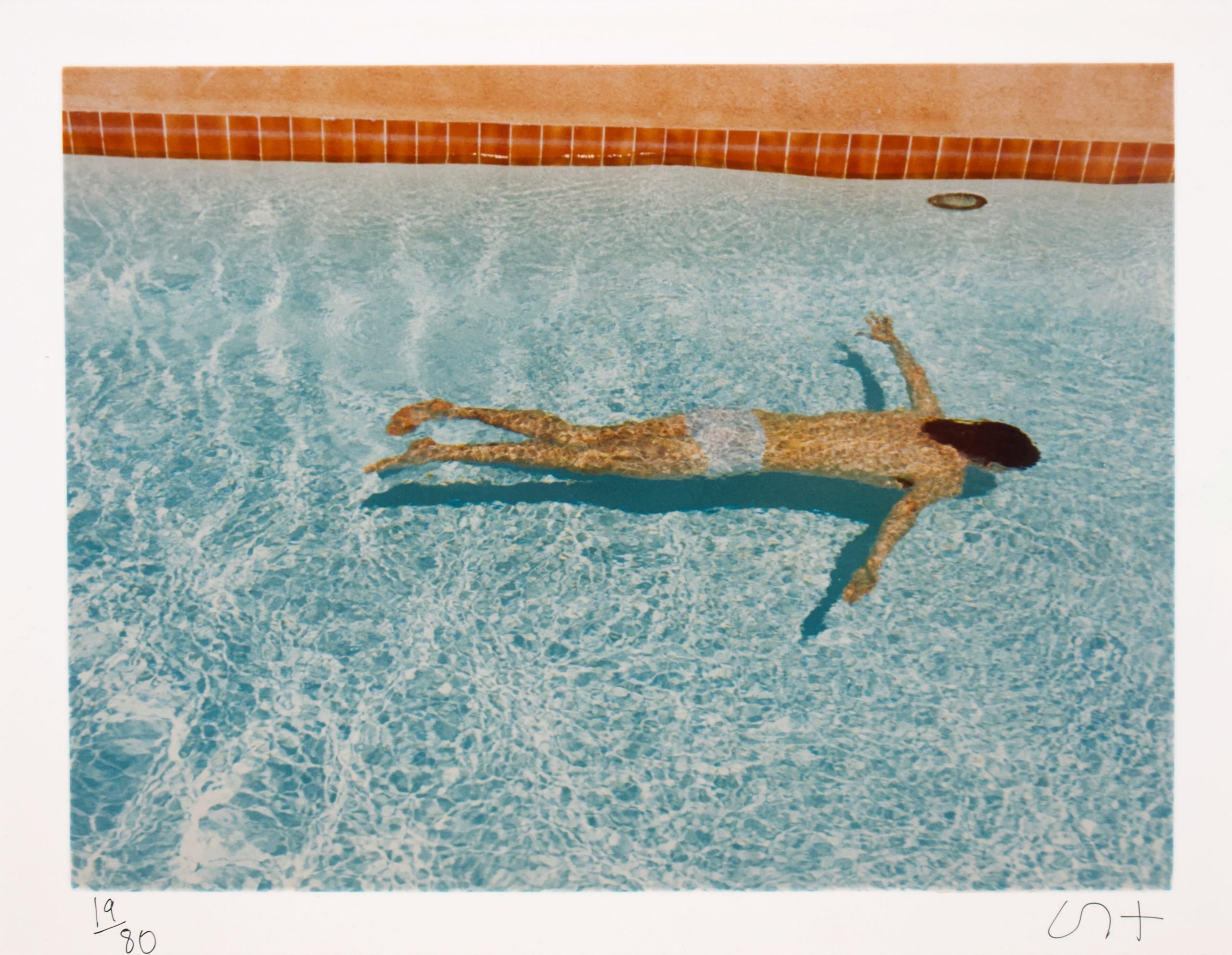

There are plenty of recognizable works among Jarmusch’s highlights, from David Hockney’s 1970s swimming pool photos, brought by Equinox Gallery, to Peter Hujar’s eerie catacomb images at Stephen Daiter’s booth.

Robert Frank’s portrait of Jack Kerouac at Pace is part of a fair-wide dedication to the late Swiss-American photographer and documentary filmmaker in honor of his 100th birthday; Jarmusch was a close friend of Frank and credits him as an influence in his own work.

Robert Frank, Jack Kerouac–NYC (1965). © The June Leaf and Robert Frank Foundation. Courtesy Pace Gallery

Several works foreground outsider figures, akin to the characters that Jarmusch tends to feature in his films. Japanese photographer Kenshichi Heshiki’s scenes of mid-century Okinawa and those living on its margins stun at Ibasho’s booth. Lisetta Carmi’s subversive images of Genoa’s trans community in the 1960s, brought by Martini and Ronchetti, are both gritty and joyful.

Lisetta Carmi, I travestiti, la Sissi (1965) Courtesy Martini & Ronchetti.

More contemporary inclusions range from Zanele Muholi’s explorations of race, as seen in her portrait OwakheX, Sheraton, Brooklyn, New York (2019), at Yancey Richardson to Dawoud Bey’s ominously dusky shot of an all-American house ringed by a white picket fence at Stephen Daiter.

Dawoud Bey, Untitled #1 (From Night Coming Tenderly, Black), 2018. Courtesy the artist and Stephen Daiter.

Of course, there are classic Surrealist works grounding Jarmusch’s curatorial strategy, 10 of which can be found at Edwynn Houk’s booth, where an entire wall has been given over to Surrealism. Among the highlights are Dora Maar’s Photo Mode II (1931) and several photos by Man Ray.

Dora Maar, Photo Mode II (1931). Courtesy Edwynn Houk.

The evening before the photo fair opened to VIPs, Jarmusch also hosted a preview of Le Retour à la raison, a compendium of four short silent films made by Man Ray in the 1920s that have been restored and scored to post-rock music by SQÜRL, Jarmusch’s experimental guitar band with Carter Logan.

“I love how Man Ray experimented with photography and film, and treated the camera as a toy,” Jarmusch said before the screening, adding that he had been playing improvisational music to these films for over a decade. The resulting score, guided by Jarmusch’s feedback-heavy guitar and Logan’s synthesizer and occasional drumbeat, feels perfectly in sync with the 100-year-old film. SQÜRL recorded it at Centre Pompidou, which is currently hosting a blockbuster Surrealism exhibition.

Alongside his cinematic work, Jarmusch is also a practicing visual artist specializing in photography and collage. He has an upcoming exhibition with James Fuentes Gallery in Los Angeles next year.

Paris Photo runs through Sunday, November 10, at the Grand Palais, Paris.