During her 35-year career, Joan Brown, a San Francisco native, painted herself as a cat, a mother, a mystic, and a long-distance swimmer. These idiosyncratic paintings, characterized by bright colors and flattened, graphic forms, blend Brown’s memories and symbology, forming nuanced, personal narratives that are at once familiar and all-encompassing.

Brown cast those closest to her—her son Noel, cat Donald, and bull terrier Bob—into her artworks with remarkable frequency. By 1990, at the time of Brown’s untimely death at the age of 52, she had produced, staggeringly, over 400 paintings and nearly 50 sculptures.

Joan Brown and her dog Bob (1961). Collection of the Estate of Joan Brown. Photo: Glen Cheriton/Impart Photography. Courtesy of the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art

Though long-beloved by a niche of the Bay Area artistic scene, including Brown’s many students (she taught for over 15 years at the University of California at Berkeley), her oeuvre has hovered obstinately at the periphery of the art historical focus.

Now that may be changing. Eighty artworks are currently on view in “Joan Brown” at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (SFMOMA) through March 12—the first retrospective of her work in over two decades. The show will travel to the Carnegie Museum of Art in Pittsburgh later in the spring, followed by the Orange County Museum of Art in Costa Mesa in early 2024.

The expansive exhibition, co-curated by Janet Bishop, chief curator of painting and sculpture, and Nancy Lim, associate curator of painting and sculpture, positions Brown as an artist deserving of another look and introduces her to a much wider audience.

So just who is Joan Brown and why should we know her name?

Young Fame and Family

Joan Brown, Noel and Bob (1964). © Estate of Joan Brown. Courtesy of the Fine Arts Museum of San Francisco.

As a young artist, Brown seemed primed for stardom. As a student at the California School of Fine Arts (CSFA), later known as the San Francisco Art Institute, she was introduced to the Bay Area figurative movement by her professor and mentor Elmer Bischoff. The only woman in the group of artists rediscovering figuration, Brown developed a style of thickly impastoed gestural canvases that teetered between figuration and abstraction.

These decadently painted works—she used so much paint that some canvases weighed up to 100 pounds—garnered immediate critical and institutional attention. In both 1957 and 1958, her works appeared in group exhibitions at SFMOMA. In 1960, Brown made her mark as the youngest artist included in the Whitney Museum of American Art’s “Thirty American Painters Under Thirty-Six.”

These early works open the new exhibition at SFMOMA. A highlight of the group is Thanksgiving Turkey (1959), which MoMA acquired in 1960 when Brown was just 22 years old.

“Thanksgiving Turkey introduces so many career-long interests—her engagement with art history (in this case, Rembrandt), focus on the vernacular, quirky compositional choices, and love of holidays,” said curator Janet Bishop, in an email.

Then in 1963, Art Forum ran a cover emblazoned with one of her paintings, the accompanying article touting, “If there is a San Francisco style, a San Francisco attitude, that style, and that attitude can be found epitomized in her paintings.”

Joan Brown, Thanksgiving Turkey (1959). © Estate of Joan Brown. Photo: © The Museum of Modern Art/

Licensed by SCALA/Art Resource, NY.

While these works earned Brown accolades, her style was still developing and Brown proved an artist who stuck to her guns artistically, for better or worse. In 1962, she and her second husband, the artist Manuel Neri, welcomed a son, Noel, Brown’s only child (although she would marry four times in her short life). Noel soon took a central role in her paintings, along with their cat, Donald, and dog, Bob (Brown even deducted Donald’s cat food from her taxes, so influential was he to her work). Though intimately personal, these paintings made direct allusions to works by titans of art history. Brown’s 1963 painting Noel on a Pony with Cloud, for instance, references Picasso’s Paulo on a Donkey, the Spanish artist’s depiction of his son.

“Brown borrowed anything from subjects and setups to compositions and mood. One way in which she connected to Picasso, in particular, was his refusal to be bound by a certain style,” noted Bishop.

Noel’s birth would also have another important influence—introducing a novel element of costuming or dress-up and play into Brown’s works. The painting Noel on Halloween (1964) pictures her son dressed up as a tiger on Halloween. The painting prefigures Brown’s self-portraits as a cat in the following decade.

By the mid-1960s, Brown was experiencing an existential shift. The exuberant decadence of her early works, with their thick slabs of oil paint that prompted one critic to say she painted like a “millionairess,” had certainly attracted collectors and afforded her young family a comfortable life. But Brown, an artist’s artist by all accounts, resented how her work had—as curator Nancy Lim writes—“been reduced by the art market to a product to be churned out and sold.” In 1968, Brown committed herself to a more pared-down aesthetic, tanking her market and forcing a break from her New York dealer George Staemplo over the change in direction.

Brown was resolute in her need for change, however, and in 1970, fate would provide new inspiration. Unable to find tubes of oil paint at her local art supply store, Brown, on a whim, purchased enamel paint, often used for house painting, as an alternative. Mesmerized by the dazzling color and quick drying results, Brown set off honing a graphic, flattened style of figures cast in bright colors and marked by eye-catching patterns, a turn that would define her works for the rest of her career.

The House Cat and the Sphinx

Joan Brown, Tempus Fugit (1970). Collection of Noel Neri, Estate of Joan Brown; © Estate of Joan Brown. Photo: Wilfred J. Jones. Courtesy of the Estate of Joan Brown.

Through the 1970s and ‘80s, Brown delved into a dazzling and kaleidoscopic world of oblique self-portraiture. These works reflected her state of mind more than any outward reality and her Self-Portrait (1970) makes that evident. Here, Brown paints herself with green eyes staring piercingly, almost hypnotically outward. Swirling around her head, like thoughts, are dogs, cats, fish, dolls—the recurring symbols in her oeuvre.

Animals had been an important presence in her works in the 1960s, offering Brown what Lim called a “stark, airtight quality” reminiscent of Henri Rousseau.

Joan Brown, Self-Portrait (1970). © Estate of Joan Brown. Courtesy of the Jack and Shanaz Langson Institute and Museum of California Art.

Cats would continue to occupy an important place in her self-portraiture until her death, as Brown became increasingly engaged with Egyptian art, after a visit to Egypt in 1977. In her 1982 painting, Harmony, Brown pictures herself split in half: painter on one side, cat on the other. These images are reminiscent of Rousseau’s dream-like visions and speak to a language of signs and ciphers that engaged Brown.

Joan Brown, Harmony (1982). © Estate of Joan Brown. Courtesy of Matthew Marks Gallery.

Brown became increasingly fascinated with Eastern philosophy and India, in particular, and was heavily influenced, along with her last husband, Michael Hebel, by the teaching of guru Sai Baba. In these years, her painted cats shifted between house cats, the Egyptian goddess Baset, and sphinxes (Brown would die while traveling in India in 1990, crushed by a falling turret, along with two assistants, while trying to install an obelisk).

These orientalizing visions revealed her ongoing interest in both art history and ancient cultures, while betraying a willingness to adopt cultural motifs that suited her quest for enlightenment and a kind of freedom from bodily constraint.

As art historian Marci Kwon wrote in her catalogue essay, Joan Brown’s New Age, “Brown endeavored to paint this mystical world without difference and yet her work teems with moments in which difference is not only present but intensified,” noting that “while the artist sincerely desired to paint universal humanity, she instead pictured the difficulty of imagining a world beyond human categorization.”

Swimming through Meditation and Ablution

Joan Brown, The Bicentennial Champion (1976). © Estate of Joan Brown. Courtesy of Anglim/Trimble, San Francisco.

While many of Brown’s late canvases seem in search of ecumenical spiritual truths, her most profound and revealing works emerge from deeply personal experiences. Swimming occupies a special and particularly effective position in this visual world. An avid swimmer, Brown participated in competitions and was a frequent swimmer in the bay. Along with five other women, Brown even successfully sued area swim clubs to allow women entry.

A section of the exhibition is devoted exclusively to these swimming portraits, each telling different stories relating to her passion for the sport. One shows Brown triumphantly holding a trophy after winning a 1976 swimming championship. Another, a double portrait with Hall of Fame swimming coach Charlie Sava, with whom she trained, presents Brown with an appealing competitive fierceness. Darker moments surface powerfully in these works as well.

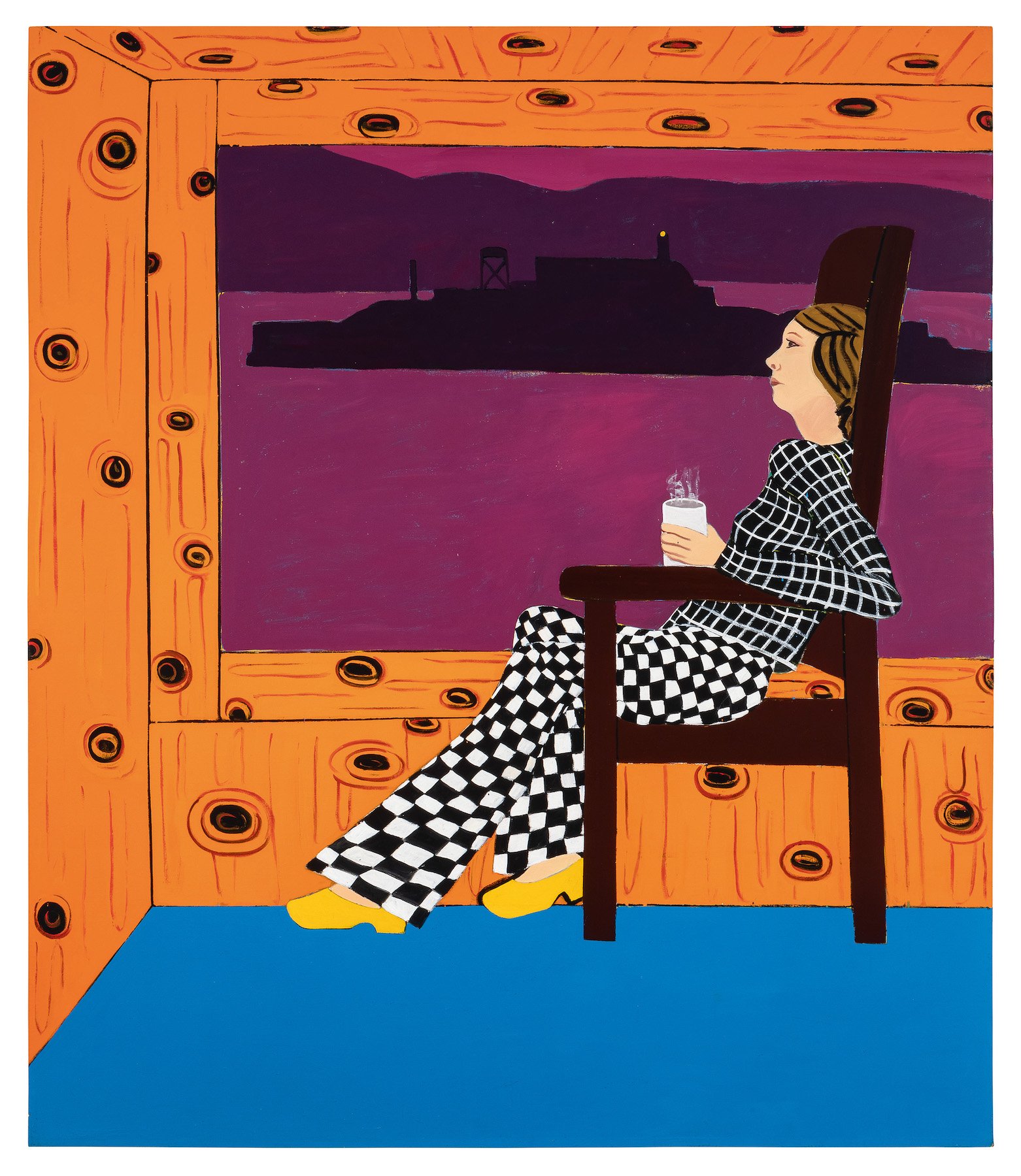

Joan Brown, After the Alcatraz Swim #1 (1975). © Estate of Joan Brown. Photo: Katherine Du Tiel. Courtesy of the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art.

In 1975, Brown participated in the women’s Alcatraz Swim—a one-and-a-half-mile race from Alcatraz Island to Aquatic Park in San Francisco. A devoted and frequent swimmer in the bay, Brown had prepared for cold waters and currents, but the tide proved particularly rough the day of the swim. Brown, disoriented, swam aimlessly for over an hour before she was rescued.

Her painting After the Alcatraz Swim #1 (1975) pictures Brown, seemingly aloof, statuesquely standing beside a fireplace. The painting hanging over the mantel, however, depicts Brown in the moment of her near-death experience, struggling to stay afloat.

Brown revisited the subject several times, reckoning with the fragility and transience of her own life. Brown was raised in an unhappy Catholic home and attended Catholic schools, and while that element of her biography is often overlooked, in these images one can find parallels with religious reckoning by water, from the great flood to Jonah to baptism itself.

These paintings reveal a tension that exists in Brown’s best works—beneath colorful and fun self-portraits lie struggle, tumult, and perseverance. As a painter, like a swimmer, Brown’s surfaces elide the kicking and exertion going on beneath the surface of the water.

“Joan Brown” is on view at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, 151 Third Street, San Francisco, California, November 19, 2022–March 12, 2023.