Opening April 5 at Anita Rogers Gallery, “Fecund Algorithms” is the latest solo exhibition by Joan Waltemath. Grappling with the complex and often contradictory relationships between the body and mind, the artist’s abstract paintings look to mathematical equations for their harmonious and inventive grid-based compositions.

Waltemath is not only an artist, however: She is also known as an influential educator and a writer, having taught architecture for years at Cooper Union and serving as editor-at-large for the esteemed Brooklyn Rail since 2001. Here, she discusses her new work, the beauty in mathematics, and what to expect at her show.

What inspired you to create the Torso/Roots series?

I am intrigued watching people perform tasks they know by heart, observing movements that seem to stem from the corporeal, rather than being directed by the mind. I want to create something that speaks directly to the body that touches our movement in the way architecture does. The more all our devices assert their dominance over the mode of our communications, the more compelled I feel to explore the multi-faceted nature of perception. How the body knows things, remembers a thing is my tabula rasa.

Joan Waltemath, Three Bodies or how I knew you were gone (east below) (2011–2013). Courtesy of Anita Rogers Gallery.

How do you decide on the placement of materials for each grid on the panel, how would you explain that in relation to the human body and mind?

I work with a grid matrix based on harmonic ratios as a way to determine the relationship of elements and the proportions of my paintings. There is a kind of precision involved in the geometry here that I really like. That’s the mind part—it wants to control everything. Then the materials come in and counter it, they have their own rules to overrule the mind. Paint has to flow onto the surface. I often see in my mind’s eye the moves I need to make—aiming to set everything into relation, into motion in sync. The geometry sets limits. Opposition is essential to keep things alive.

You choose interesting titles for your work. What were you thinking about when deciding them, and should it affect the way a viewer experiences your work?

Often a relationship or movement becomes an analogue for events, perceptions, or realizations in my life, so the titles are a way to acknowledge that aspect. If the unfolding of a painting enables an experience or thought to happen, that’s great! Some people need language or narrative to find a point of entry into a painting—on the other hand, the title could affirm an understanding after the fact.

I mean, it’s an abstraction, so you have to go somewhere with it: It demands an engagement from the audience since I’m distilling the experiential, not directing where it should go.

Joan Waltemath, RA’s dream (East Below) (2012–2016). Courtesy of Anita Rogers Gallery.

The Torso/Roots pieces are based on a grid derived from harmonic mathematical relationships, do you think perhaps your approach may lure the more “mathematical mind”?

Recently I was making my way through a series of publications the Getty released on Latin American Surrealism. What a surprise to discover that during the post-war time artists were coming to terms with Freud and the notion that we all see different things when we look at works of art, that our perceptions are relative to what we already know and have experienced. It’s not such an extraordinary notion for contemporary art; we can easily acknowledge a mathematician would recognize aspects the architectural mind might see as something else and vice-versa!

What memorable response have you had from your work?

During my 1994 exhibition “Zwischenzeit” at Stark Gallery, a beautiful young woman opened the door and ran towards my 12-foot square drawing; she jumped, kicking her leg up high to meet its center. “This is cool, isn’t it?” she said as she turned in mid-air towards her b-boy friend. They ran out. I was stunned, it showed my initial construct of harmonic progressions in black and white really could speak to the body. The drawing is now in the collection of the Hammer Museum at UCLA, thanks to Wynn Kramarsky.

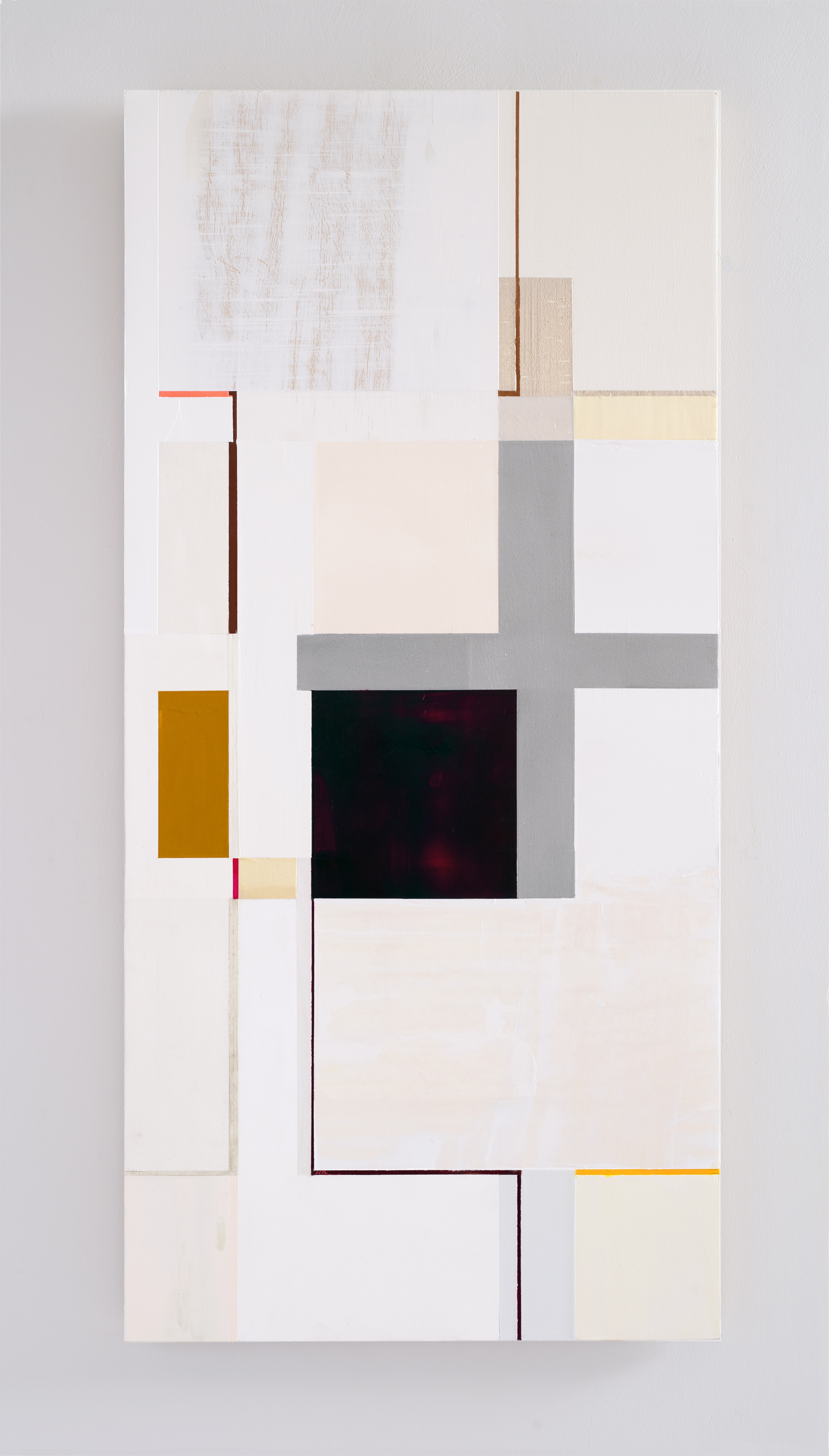

Joan Waltemath,

interwoven (East 2 1,2,3,5,8…) (2013–2016). Courtesy of Anita Rogers Gallery.

What is your favorite skyscraper or building, and why?

I don’t know favorite, but here is a thought: When I moved to Manhattan I took a loft across from the Stanford White Bowery Savings Bank. The pediment was visible through the window and the clock was still working in those days. It held a distant feeling of Rome: I could look down on the unique portico of the bank, whose outer façade ran parallel to the Bowery, while the inner one was aligned to the cardinal directions. The way White had set the relationship between these two orientations was significant for me; in plan it was a parallelogram not a rectangle. I used to sit inside the bank and make phone calls in the wooden phone booths, light poured in two stories above me through the amber glass, sounds echoed in a familiar way and the framed yellow marble slabs with their lighter colored veins running on a diagonal felt like Modernist painting. I could love the way the architectural void held my body. I haven’t been inside for many years, it’s no longer a public space. The clock stopped sometime in the late 80s after it was sold.

What is the most important first impression that you hope your viewers will get from your work?

One that is uniquely their own.

The artnet Gallery Network is a community of the world’s leading galleries offering artworks by today’s most collected artists. Learn more about becoming a member here, or explore our member galleries here.