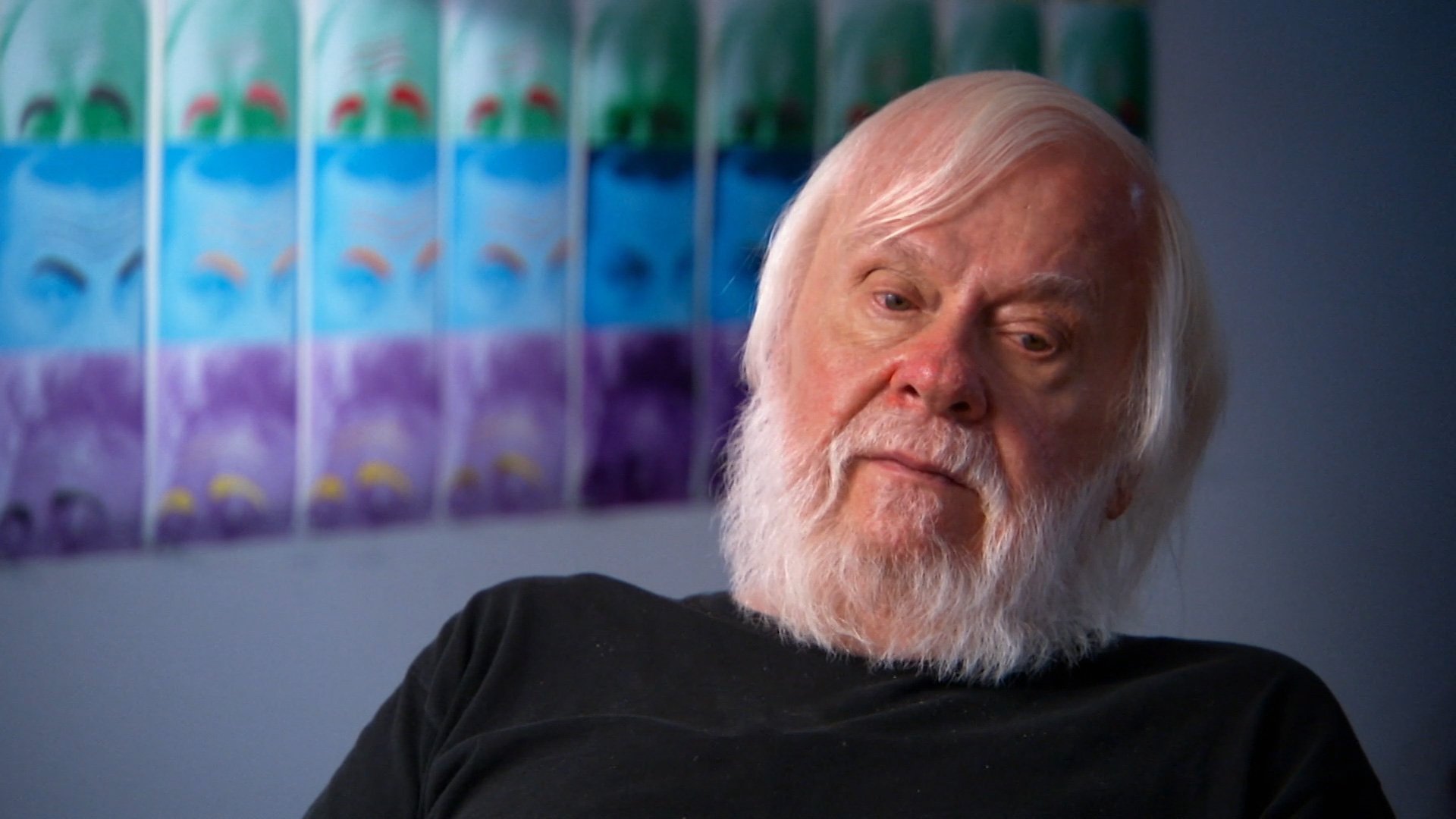

Nearly four years after the death of iconic conceptual artist John Baldessari, heirs managing his estate and eponymous trust are locked in litigation with his former gallery, two insurers, and art fabricators who claim the heirs have effectively bilked them out of millions.

The artist’s children allege the artist’s late gallery, Marian Goodman Gallery, and two insurers are responsible for millions of dollars’ worth of damage to his artworks that were left in their care.

Meanwhile, the trust itself was sued for breach of contract over ownership of works the fabricator says were completed in collaboration with the artist while he was alive. The fabricator said interference by the estate and issues with the representative heirs resulted in cancellation of a major planned show at Gagosian Gallery—and the heirs have countersued.

Baldessari’s children, Annamarie and Antonio, along with JAB Enterprises, are listed as plaintiffs in the first suit, filed in Supreme Court in New York in October 2022. XL Specialty Insurance and AXA Insurance are defendants along with Marian Goodman Gallery.

According to the lawsuit, in order to further the artist’s legacy following his death in January 2020, the heirs decided to end the relationship with Marian Goodman and transfer all the assets to a different gallery, identified later in the complaint as Sprüth Magers.

However, on retrieving the artists’ works from Marian Goodman, the heirs discovered that many of them were damaged, “as a result of MGG’s wrongful conduct while these works of art were on consignment to,” or in the possession of the gallery, according to the complaint.

The Baldessaris say they immediately gave notice to Marian Goodman Gallery and the insurers. The complaint alleges that the gallery breached its fiduciary duty to keep the art safe and free from damage, that the gallery was “grossly negligent” in the handling of works, and that it failed to address the damage immediately.

Attorneys for Marian Goodman Gallery characterized the lawsuit as baseless in an email to Artnet News.

The heirs say they incurred conservation costs when they took action upon discovery of the damage. In all they say there are 55 Baldessari works of art that have been identified as damaged as a result of the gallery’s wrongful conduct. “Some are a total loss. All others require conservation and are diminished in value as a result of the damage,” the plaintiffs claim, according to court papers. They allege that Marian Goodman Gallery and the insurers have failed and refused to reimburse the losses, which they currently estimate at more than $21 million.

The attorney for the Baldessari estate declined to comment. Attorneys for the insurers did not respond to request for comment.

In the emailed statement, a Marian Goodman Gallery attorney said it “is deeply saddened that after a long and productive relationship with John Baldessari, one of America’s greatest artists, his estate brought this baseless lawsuit…The gallery has been vigorously defending the claims since they were first asserted,” said Adam Cohen of Kane Kessler. “Although we cannot comment as to the specifics of the case because it is pending litigation, we are confident that the gallery will ultimately prevail and that these claims will be shown to lack any merit as to the facts or the law.”

In the other, separate lawsuit New York-based Beyer Projects sued the trust, and by extension Annamarie and Antonio, for breach of contract and tortious interference in relationship to a series of sculptures created in collaboration with the late artist. The suit was filed in May in U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York.

According to the complaint, for the past 25 years, Beyer has been working with some of the world’s top artists to help them expand into the medium of sculpture. Beyer partners with artists “from early in their projects—whether realizing a sketch on the metaphorical back of a napkin or replicating fully realized maquettes,” according to the suit. Beyer says its principals personally invest in its collaborations through project funding, research, development, production supervision, and placement for works in private collections or museum.

One such collaboration was with Baldessari, who despite already being established as one of the top conceptual artists in the world, “did not have the background in, or the ability to create, large-scale sculptures,” according to the complaint. In 2005, Baldessari and Steven Beyer—a principal of Beyer Projects with his wife, Melissa—agreed to work together to create sculptural artwork. “This made sense. John had an appetite to extend his work to new media, and Steven Beyer has decades of experience and accomplishment in sculpture, extending back to when he was one of the youngest Guggenheim Fellows in that foundation’s history,” according to the complaint.

John Baldessari, Camel (Albino) Contemplating Needle (Large). Image via PACER

Baldessari and Beyer entered into a series of agreements that generally had “three material aspects,” according to the complaint: for a given work, Beyer would create editioned sculptures in collaboration with the artist, fully bearing the costs associated with bringing each sculpture in the edition to life; second, one sculpture would be wholly owned by Baldessari and one would be wholly owned by the Beyers; third, the remaining sculptures would be co-owned, and the profits from their sale would be split 50-50 after Beyer Projects recouped its costs.

Under these contracts, Beyer says it spent over $2 million creating 11 different works comprising over 70 separate sculptures. While the artist was alive, “the sale of the sculptures went smoothly. For example, all of the copies of the sculpture Beethoven’s Trumpet (with Ear) were sold with money distributed as agreed.”

But things went awry after Baldessari passed away.

According to the complaint, it was the artist’s “deeply held wish that eventually the sculpture would be shown by a gallery that could show all the work together. . .Only about four such galleries have the physical and financial capacity to exhibit his entire sculptural oeuvre at once.”

Beyer executed a contract with Gagosian Gallery to sell all the co-owned as well as the Beyer-owned artwork. An exhibition was planned for this past May and was expected to bring in upwards of $10 million.

But there was a hitch—the Baldessaris claim that the art the Beyers say is co-owned “was always 100 percent owned by John,” and was on consignment to the Beyers.

When Gagosian gallery became aware of the demands and “this cloud of ownership, however baseless,” the gallery canceled the exhibition, according to the complaint.

Beyer is alleging greed on the part of the Baldessari children, writing in the complaint: “Acting as trustees for the Trust, [Annamarie and Antonio] decided to try to take everything from Beyer Projects. They demanded all the Co-Owned art as their exclusive property, with an exclusive right to all profits from their sale, despite contracts that provide expressly otherwise.”

Beyer Projects then found “itself in the unfortunate position of having to sue the children of an artist they loved, someone with whom they intimately collaborated, and an artist whose legacy means everything to them,” according to the complaint.

In a response filed in August, the Baldessaris denied most of the allegations and noted that Beyer had not sold any Baldessari works of art in seven years, since 2016.

The heirs sought to dismiss most of the Beyer claims and also filed their own counterclaims. Along with damages and accounting, they are seeking an order requiring Beyer to return all of the sculptures and related property.

Beyer Projects’ attorney did not immediately respond to request for comment. Gagosian Gallery declined to comment. The attorney for the Baldessari estate declined to comment on the Beyer case.