On a long weekend in late May 1963, Andy [Warhol], Bob Indiana, Marisol, and I went up by train to Old Lyme, Connecticut, and visited Wynn Chamberlain. He had rented a farmhouse for the summer.

Eleanor Ward, owner of the Stable Gallery, who showed Andy, Bob, and Marisol in New York, rented an old stone icehouse on the same property. Wynn cooked a wonderful dinner and we drank lots of wine. After dinner, Wynn served 140-proof black rum and I drank a lot. We said good night at about two o’clock.

Andy and I slept in a bedroom, in the same bed, but we didn’t have sex. My brain was fried by the rum. I just dropped my clothes, fell naked onto the bed, and passed out.

I woke up about 4:30 to take a piss. In the faint traces of early morning light, Andy was next to me, his head resting on his hand and elbow, wide-awake, looking at me. I went to the bathroom, bleary-eyed, and then back to bed.

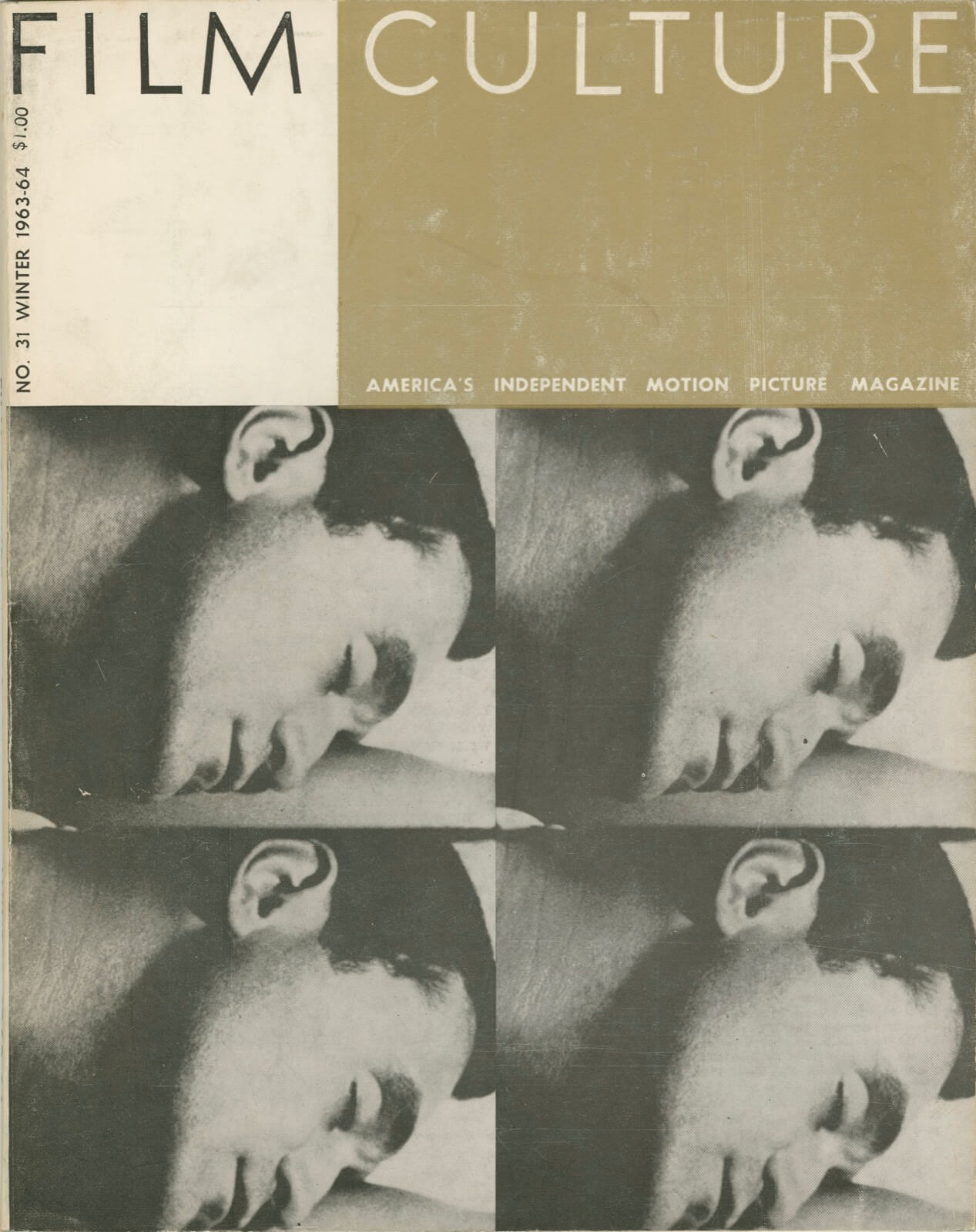

Andy Warhol. Lasse Olsson / Pressens Bild.

I woke up two hours later, and Andy was still looking, his eyes open wide. “What are you doing?” I was still drunk, and confused.

“Watching you.”

I took another piss and went back to sleep. I woke after a while and he was still doing it. “What are you doing?” I had a rubber tongue.

“Watching you sleep,” said Andy sweetly.

As it became lighter, I saw him more clearly. Fifteen minutes later, I turned and he was looking at me with Bette Davis eyes. I kissed him on the cheek. “Are you okay?”

“Yes.”

“Are you sure? Take off your shirt. It’s so hot.” He declined. I tried to take it off and he giggled. Andy was wearing limp Jockey underwear. “And take off your underwear.” His skin was very white and soft, and he had hairless, beautiful boy’s legs. It was sweltering. I was wet from sweating in my sleep, so there was no thought of cuddling. I kept my eyes shut, but knew he was still looking.

I woke two hours later and he wasn’t next to me. In the bright morning, he was dressed, sitting in a chair at the foot of the bed, still staring at me. “Why are you watching me?”

“Wouldn’t you like to know!”

I had a horrible hangover and headache. I took a piss, stumbled back and gave his shoulder a squeeze, and dove back to sleep.

It was not my problem that he wanted to look.

The next time I woke and looked, Andy was in bed with his clothes on, his head sunk in the pillow, drowsily looking at me. He was keeping himself up. It was 11:30 a.m. and sunlight came sharply into a corner of the room, heating it up to a tropical rain forest. Sweat poured from my body.

When I woke up at 1:30, Andy was gone. He was on amphetamines and had watched me sleep for eight hours. That night, Andy got the idea for the movie Sleep.

We went back to New York early on Monday afternoon. At the crowded Old Lyme railroad station, we waited interminably for the delayed Boston–New York train. Andy talked, as he often did, about making a movie, what he wanted to do, the kind of movie.

“I want to make a movie,” said Andy. “Do you want to be the star?”

“Yes! I do!” Snuggling close, I pressed up against him like a cat. “What do I have to do? I do everything.”

“I want to make a movie of you sleeping.”

I was a bit surprised. “Great!”

“Just you sleeping.”

“I can do it.”

“I’m sure you can.”

“I want to be a movie star!” I said. It was the American dream. Andy Warhol had asked me to star in his first movie and be his first superstar. I pronounced the words clearly with a downbeat. “I want to be a movie star!”

“I know you do!” said Andy.

“I want to be like Marilyn Monroe.” This was before Marilyn became the legend, before she entered the realm of myth. She had committed suicide only nine months earlier, on August 5, 1962. Her career was tottering, and she was the failed superstar, the union of the divine and the profane. Andy had captured that in his first Marilyn paintings, done right after her death.

And I wanted that for myself. I was drawn to her suicide and her stardom.

“Oh, John!” said Andy happily.

In the overcrowded, rattling train, everybody was unattractive and sweating. Andy said, “When was the first time you wanted to be a movie star?

“When I was nine years old in the Hotel Pierre!”

“What?”

“You remember, I told you.”

John Giorno in New York, February 2, 1991. Photo by Michel Delsol/Getty Images.

In October 1946, when I was nine years old, I had an eye operation. There had been a tumor in my left eye, between the optic nerve and the brain. For about a year and a half, my teachers had noticed that I had difficulty reading, and problems with my sight. I had double vision and the blurring in one eye got worse.

My surgeon, Dr. Algernon Reese, was a world-renowned eye specialist, famous for several innovative operations. His genius was that he adapted surgical technology developed during World War II to modern eye surgery. Previously, my operation would have entailed cutting the optic nerve, removing the eye through the eye socket, and cutting out the tumor, resulting in blindness and a glass eye. Instead, Dr. Reese used electric knives to precisely cut away my brow bone from my skull, then removed the tumor, and put the bone back. It worked: my sight was saved. I was the first patient to have this procedure, and my parents were brave to allow it.

The tumor was benign. After a three-hour operation and a six-week recovery in the hospital, I was taken to several medical conferences, photographed for The New England Journal of Medicine, and showed off, like a prize. In 1946, at an American Medical Association meeting at the Hotel Pierre, Dr. Reese presented me. My damaged eye was behind a black eye patch, which was taken off to reveal that my eye looked like a rotting mushroom.

Afterward, at the press conference, they led me into a room, and there were two dozen photographers with big old-fashioned Hollywood flashbulb cameras. In the blinding light, I had the joyous feeling that this was what it was like to be a movie star, Rita Hayworth, Judy Garland, Betty Grable. In the waves of flashbulb light, I said to myself, I want to be a movie star. I liked the feeling. It was scary, but I felt at home.

Then they led me out of the room.

“And then,” I told Andy again, “I was back to being alone with a sick eye.”