Johnnetta B. Cole, the director of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African Art (NMAA) in Washington, DC, has broken her silence on the growing controversy surrounding the institution’s exhibition of the art collection of disgraced comedian and alleged serial rapist Bill Cosby.

In an editorial published on the Root, Cole stressed that “as someone deeply committed to human rights for all people, and especially because of my long-standing engagement with women’s issues, I am devastated by the allegations and revelations surrounding Bill Cosby.”

She went on to defend NMAA’s decision to keep the “Conversations: African and American Artworks in Dialogue” exhibition on view, stating that “it is my responsibility as the museum’s director to defend the rights of the artists in ‘Conversations’ to have their works seen. It is also my responsibility to defend the rights of the public to see these works of art, which have the power to inspire through the compelling stories they tell of the struggles and the triumphs of African-American people.”

While Coles allows that “I would not have moved forward with this particular exhibition” had she been aware of the allegations against Cosby, she maintains that the Smithsonian is keeping the show on view “because art speaks for itself, not its owners.” She also does not comment on whether she believes Cosby is guilty.

This past October, a stand up bit from comedian Hannibal Buress about the Cosby rape allegations began circulating, shortly before “Conversations” opened on November 9. This was nine years after The Today Show ran an interview with lawyer Tamara Green, who claimed Cosby drugged and raped her after lunch at a restaurant in LA.

Following the viral success of the Buress video, new accusers began coming forward; the current total is 46.

Simmie Knox, Portrait of Bill and Camille Cosby (1984).

Photo: David Stansbury, permission courtesy of the artist. The Collection of Camille O. and William H. Cosby Jr.

As increasingly more organizations began cutting ties with Cosby, artnet News wondered whether the Smithsonian would join those ranks, and remove the works from Cosby’s collection (about one-third of the 171 pieces on display) from the then-newly-opened show.

In response, a museum representative defended the exhibition without mentioning Cosby by name, telling us that the show “gives us the opportunity to showcase one of the world’s preeminent private collections of African American art, which will help further meaningful dialogue between Africa and the African diaspora.”

In the months that followed, the museum continued to stand by the show, even as the public increasingly turned on Cosby,

In July, the Smithsonian came under further scrutiny when it was revealed that Cosby and his wife Camille had made a substantial $716,000 donation to the NMAA to cover the cost of the show. The Alliance of American Museums maintains that a museum “should make public the source of funding when the lender is also a funder of the exhibition,” but the contribution was not mentioned in the Smithsonian exhibition press release or website.

“We never tried to hide the gift or loan, and when asked by the media how the exhibition was paid for, we provided that information,” Cole told the Root. “In retrospect, we clearly could have and should have made that information more explicit at the outset.”

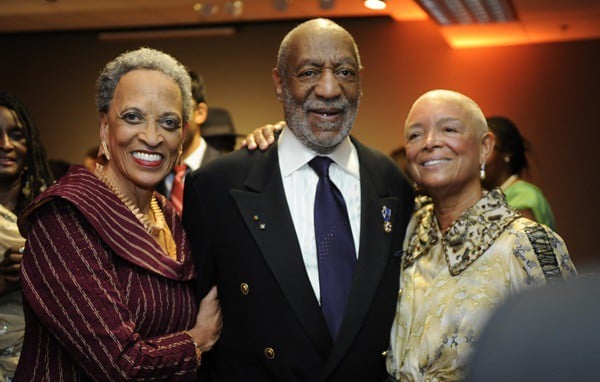

Bill Cosby.

Photo: © 2014 Patrick McMullan Company, Inc.

In her defense of the exhibition, Cole downplays the show’s many mentions of Cosby in its wall texts and written materials. The Washington Post‘s Philip Kennicott called the show “an exercise in hagiography, full of soft-focus and flattering images of the Cosbys, a painting by their daughter and multiple citations from the couple explaining their love of art.”

Cole’s contention that “stories told through art by African and African-American artists can contribute to our understanding not only of why and how race and other differences continue to divide us” is certainly a valid one, and may very well apply to the works in “Conversations.” But displaying a glowing Cosby family portrait is something else entirely.

By not altering the exhibition to remove mentions of Cosby, Cole is downplaying the import of the serious accusations of 46 women who came forward and told their stories of sexual abuse. Jillian Steinhauer at Hyperallergic has some suggestions on what the institution can do about this controversial collection, as well as an open letter to the Smithsonian with a request to strip “the show of its hagiography” and honor the 46 women’s accusations.

Related Stories:

Bill Cosby’s Daughter Artist Erika Ranee Curates New York Show

Philadelphia Paints Over Mural Depicting Disgraced Entertainer Bill Cosby

Teen Artist Rodman Edwards Creates Creepy Sculpture of Bill Cosby Naked for TV Hall of Fame

Street Artist FLOOD Shames Bill Cosby on the Streets of Manhattan