It seems like only yesterday that FOMO, the pressure-packed acronym denoting a “fear of missing out,” was inescapable in the global art world. No matter how active you were, every time you opened Instagram or checked your email, there were multiple transmissions from peers, friends, and rivals about new exhibitions and events happening somewhere else in the world where you were not… but felt like you should be for the sake of your career, your personal network, your social-media following, or all of the above.

But every day, FOMO is being overtaken further and further by the yin to its yang, the day to its night, the chaser to its shot: JOMO, the joy of missing out. The phenomenon represents the next natural step forward from “fairtigue,” “auction exhaustion,” and all the other new phrases invented to put a cute, manageable face on the art world’s increasingly body-wracking treadmill of events.

“The ‘See you in Miami?’ email sign-off will begin to pervade my inbox likely starting next month, but already, three people—two gallerists and one collector—have expressed to me their delight in sitting it out this year,” says art advisor Liz Parks. And the sentiment extends far beyond her network.

The lines to get into Art Basel in Miami. Courtesy of Art Basel.

A Brief History of JOMO

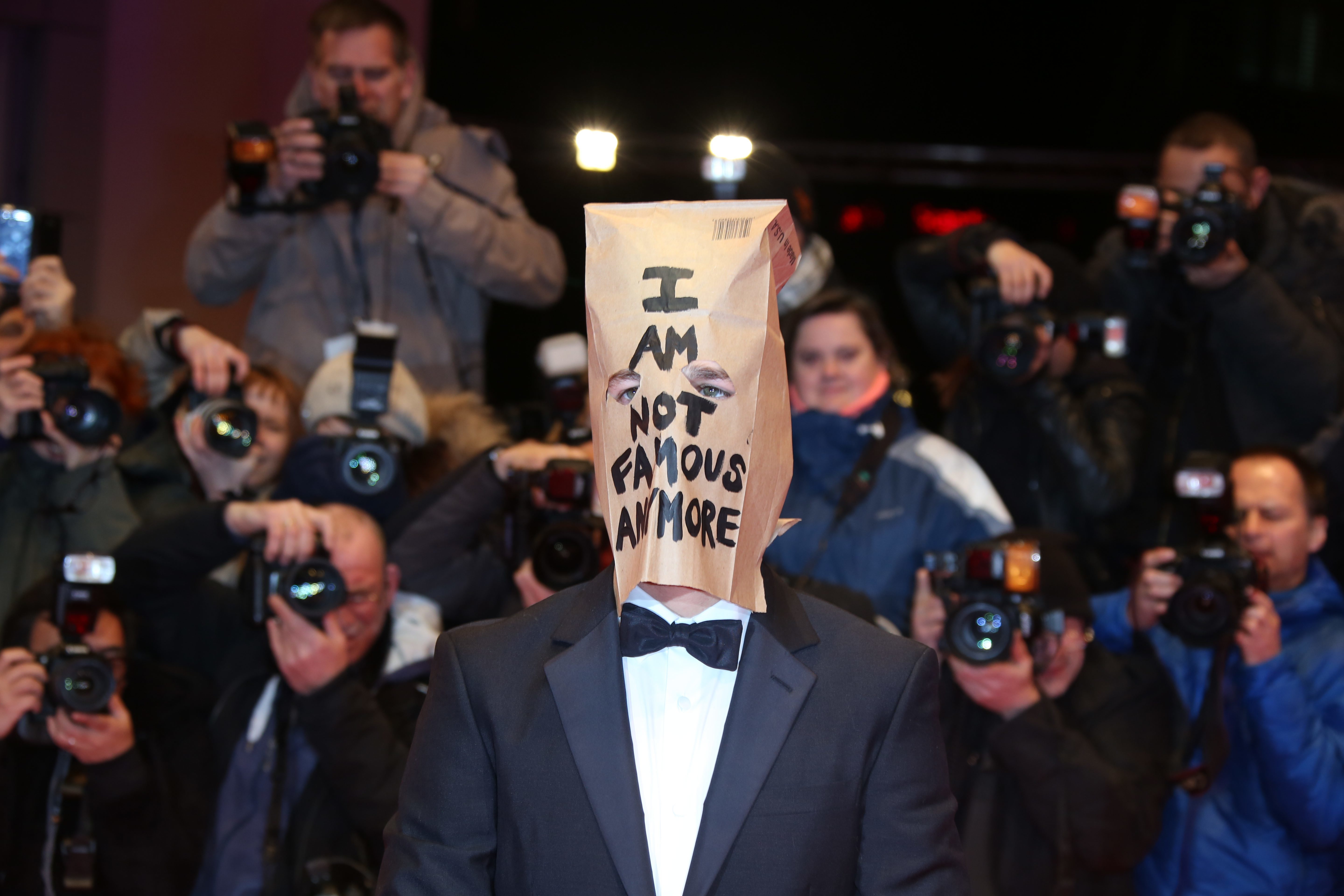

It doesn’t take a forensics team to figure out how we got here. The explanation is clear based on even a cursory look back at what art critic Martin Herbert—whose recent book Tell Them I Said No examines artists like David Hammons and Cady Noland, who opted out of the art scene midway through their careers—calls the “scalar expansion” of the art trade over the past 20 years. Somewhere along the way, the art world hit a tipping point where it became impossible to even strive to see everything and be everywhere—and with that collective resignation, FOMO mutated into JOMO.

“I feel like my grasp of what’s going on is only okay, but I’m also decreasingly likely to guilt myself over that,” Hebert told artnet News. “I see that attitude in other people too: a reflected sense that the art world has gotten too big to process.”

A few figures help illustrate just how extreme the proliferation of events has become in the art world. The number of worldwide art fairs mushroomed from 68 in 2005 to somewhere between 225 and 300 by early 2015—and still floats close to the high end of that range, according to art economist Clare McAndrew.

The Biennial Association, meanwhile, currently lists 259 biennials, triennials, or similar art exhibitions in its directory. And while it’s difficult to find an estimate for the number of gallery exhibitions now mounted each year in a sector of the trade where Gagosian alone boasts 17 permanent spaces, consider that the artnet Price Database went from tracking auction results for about 8,300 artists in 1988 to 71,621 last year. Each of these events is also accompanied by its own murderer’s row of dinners, cocktail parties, and breakfast buffets to entice those who keep the art market churning.

Svend Brinkmann, author of The Joy of Missing Out. Courtesy of the author.

In this way, the art world is simply a heightened version of the real world, where social media, smartphones, urbanization, and other factors have combined to make life more distracting and demanding than ever. The term FOMO, on which JOMO is based, can be traced back to 2004, when it was coined by venture capitalist Patrick McGinnis while he was a student at Harvard Business School. He had arrived from a small town in Maine and found himself overwhelmed by the activities and options available to him. (He now has a podcast, called “Fomo Sapiens,” on which he interviews business leaders about how they prioritize.)

As Danish psychology professor Svend Brinkmann writes in his book The Joy of Missing Out, published in February, saying no is a skill “we lack as both individuals and as a society.” But, he argues, it is one we must cultivate to counteract lives based on “overconsumption, untrammelled growth, and whittling away at our natural resources.” (Brinkmann declined to speak with artnet News for this story, citing his busy schedule, which feels on brand.) This particular thread of self-help seems to be catching on: recent best-sellers in this genre include Chris Bailey’s Hyper Focus and Cal Newport’s Digital Minimalism: Choosing a Focused Life in a Noisy World.

The JOMO Resistance

Some market players take heart in the notion that the most important transactions never happen out in the open. “The most important works that come to market never make it to a fair or an auction. They don’t need the visibility help,” says one dealer who requested anonymity. “When you come to that realization, going out of one’s way to see ‘B’ material at a fair or auction becomes less desirable.”

Still, some members of the art caravan can’t afford a deep indulgence in JOMO. Chief among them are advisors, particularly those focused on younger clients with small children or businesses they are still actively in the process of building. “One of the most important aspects of the advisor’s role is to see as much as possible and speak to as many people as possible in order to divine some sort of signal in the noise that is the market,” says advisor Benjamin Godsill.

He also points out that, for more experienced collectors, any trend toward missing out probably has less to do with embracing joy than with recognizing necessity. He regularly meets with his clients at the start of each season to map out which fairs qualify as must-see—a determination increasingly informed by taking a wider view of the destination city, including what local gallery shows, institutional exhibitions, and other special events are accessible during a fair’s run.

David Shrigley’s Opening Hours (2016). Courtesy of the artist.

Dealers on the rise form another group pushing back against the tide of JOMO. “I always make sure to go to anything directly related to an artist I’m working with, wherever it is in the world,” New York gallerist Meredith Rosen says. “Everything else is secondary to that.”

Parks notes that the fact that collectors are increasingly comfortable buying art off a JPEG makes them feel more sanguine about missing market events when they don’t fit easily into their schedules. (Plus, the plethora of art-fair photos on Instagram means you can pretend you saw that installation everyone was talking about regardless.)

“I go to Frieze this week as their proxy,” Parks says ahead of the art-fair bonanza in London. “If they experience JOMO as a result of not being there, good for them. And I suppose as I walk through Regent’s Park on Wednesday, I can simultaneously rack up some anti-FOMO points. Everyone wins.”

When applied to the art world, JOMO is above all about prioritization. “I don’t think skipping the occasional art fair has any effect on how well I do my job,” says Eric Gleason, a director at Kasmin. “But it definitely makes me a better father.”

With such a proliferation of activities, the joy comes from picking the ones you really want or need to attend, and leaving the rest behind—without guilt. “If I read a report about an art fair I wasn’t at—which is most of them—I’m usually glad I wasn’t there, but a part of me rehearses a scenario in which I alight upon something great,” Herbert says. “And then the next fair rolls around and, quite probably, I still don’t go.”