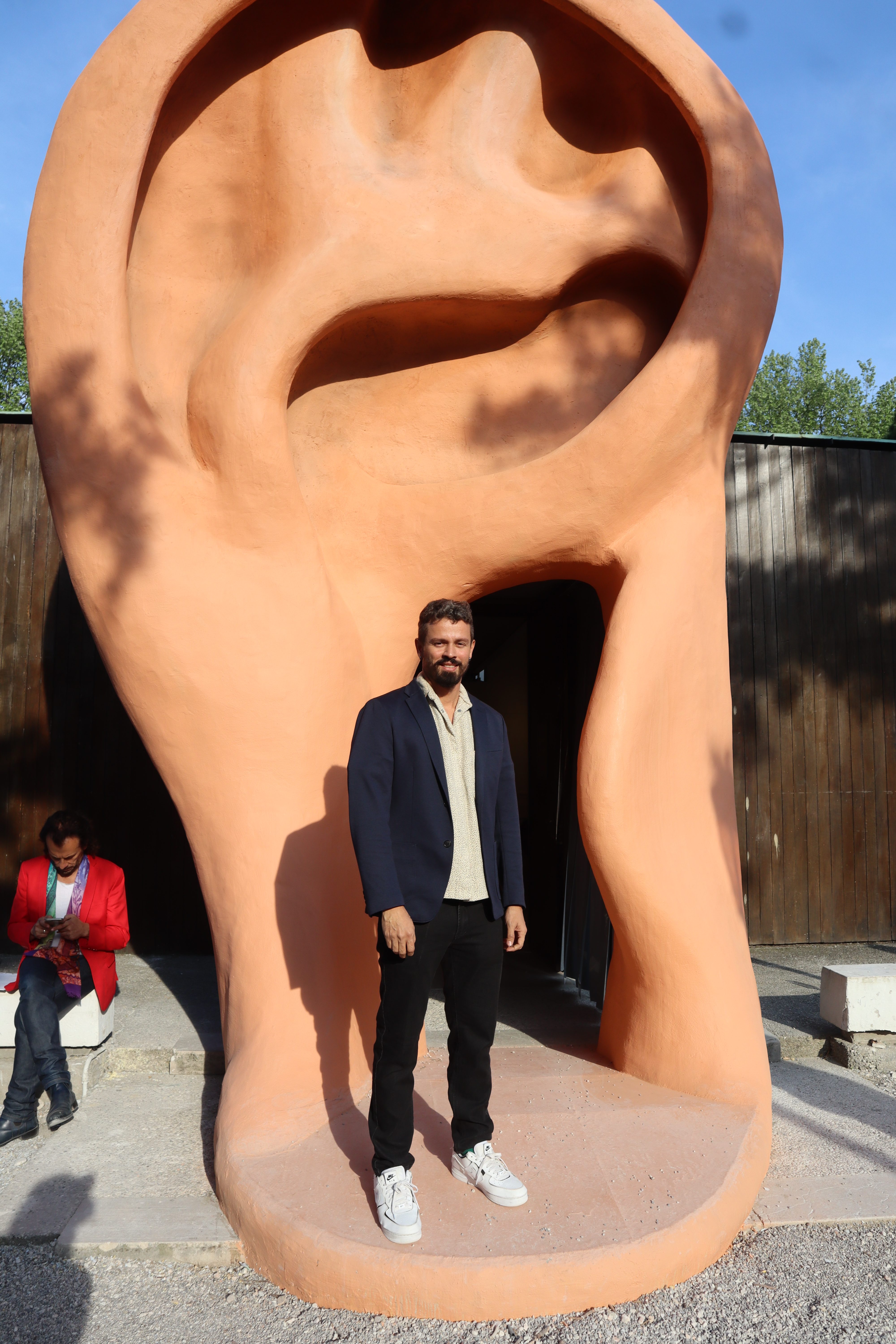

In one ear and out the other. That’s what you get with the Brazilian pavilion at the Venice Biennale, where you literally walk through two ear-doors to experience the work, which presents a somewhat oblique critique of the country’s contemporary sociopolitical landscape.

Artist Jonathas de Andrade has created a playful pavilion that draws on a system of more than 250 Brazilian idiomatic expressions relating to the body. Titled “Com o coração saindo pela boca (With the heart coming out of the mouth),” it includes sculptures, photographs, and a video installation that take these expressions as their points of departure.

“They are metaphors that resonate with what we are experiencing politically and socially in Brazil right now,” De Andrade told Artnet News. “It speaks to the political temperature of the unfolding disasters: the Amazon, the human rights, the vaccine denial, and so on.”

In the first room, a rotten finger repeatedly presses the wrong button on an electronic ballot box, taken from an expression referring to someone who contaminates whatever he or she touches, and an unavoidable evocation of the widespread political corruption in Brazil under its right-wing president, Jair Bolsonaro.

Installation view of Jonathas de Andrade, “Com o coração saindo pela boca/With the heart coming out of the mouth,” at the 2022 Brazilian Pavilion in Venice. Courtesy of Ding Musa/Fundação Bienal de São Paulo.

The colorful pavilion adopts the visual vernacular of science fairs, which De Andrade used to visit as a child, conveying a sense of eye-popping dioramas and displays. On one side of a room, a suspended head bobs up and down, and in the center, a giant lip sculpture on the ceiling slowly spews out a red inflatable heart that continues to expand to fill the room, pushing visitors against the walls.

The phrase the work expresses inspired the title of the exhibition, and is a key to understanding De Andrade’s poetic voice. “It’s an expression which I love because it’s very ambiguous,” he said. “It speaks both to being in the midst of a tragedy but also being in deep emotion—so we have to decide if we are going to enjoy the emotion or if we’re dealing with a disaster. Sometimes it’s both. This heart that comes out of the mouth softly becomes a birth. It’s a tongue, it’s organs, it’s vomit, it becomes lungs, it goes and pushes people to squeeze into the space and figure out how to negotiate the space together again.”

Installation view of Jonathas de Andrade, “Com o coração saindo pela boca/With the heart coming out of the mouth,” at the 2022 Brazilian Pavilion in Venice. Courtesy of Ding Musa/Fundação Bienal de São Paulo.

De Andrade uses his practice as a catalyst for social change, responding particularly to the inequities of race, class, and labor in Brazil. As he sees it, the poetic absurdity of some of these expressions—when taken literally or translated—opens up the space to forge new meanings. “Brazil’s atmosphere feels stuck at the moment,” he said. “I think this is how we can recognize the force, the power of the collective body to create a new political libido and change the mood.”

It’s a knotty display that needles many of the issues facing contemporary Brazil without being too explicit—no need to spell out the meaning of the bitten-off tongue that sits on the floor of one room, or the rolled-up banknote on the wall of another. De Andrade’s hope is that art can become a space in which to untangle some of these issues and find a path to break free from oppression.

As he navigated the tone for an exhibition that is openly critical of the country he is representing, the artist said it was a challenge “trying to find and read what is possible in the Brazilian context, which is quite harsh”—hence his somewhat indirect approach. But for the possibilities this kind of confrontation opens up, he said, “It’s worth taking a risk.”