In 1962, Joseph E. Yoakum had a dream that told him to make drawings.

He was 71 then, a retired veteran and one-time circus hand living in Chicago. He had no experience making art. But for the next decade of his life—his last, it would turn out—drawing was what he did, churning out some 2,000 wondrous pieces in the process.

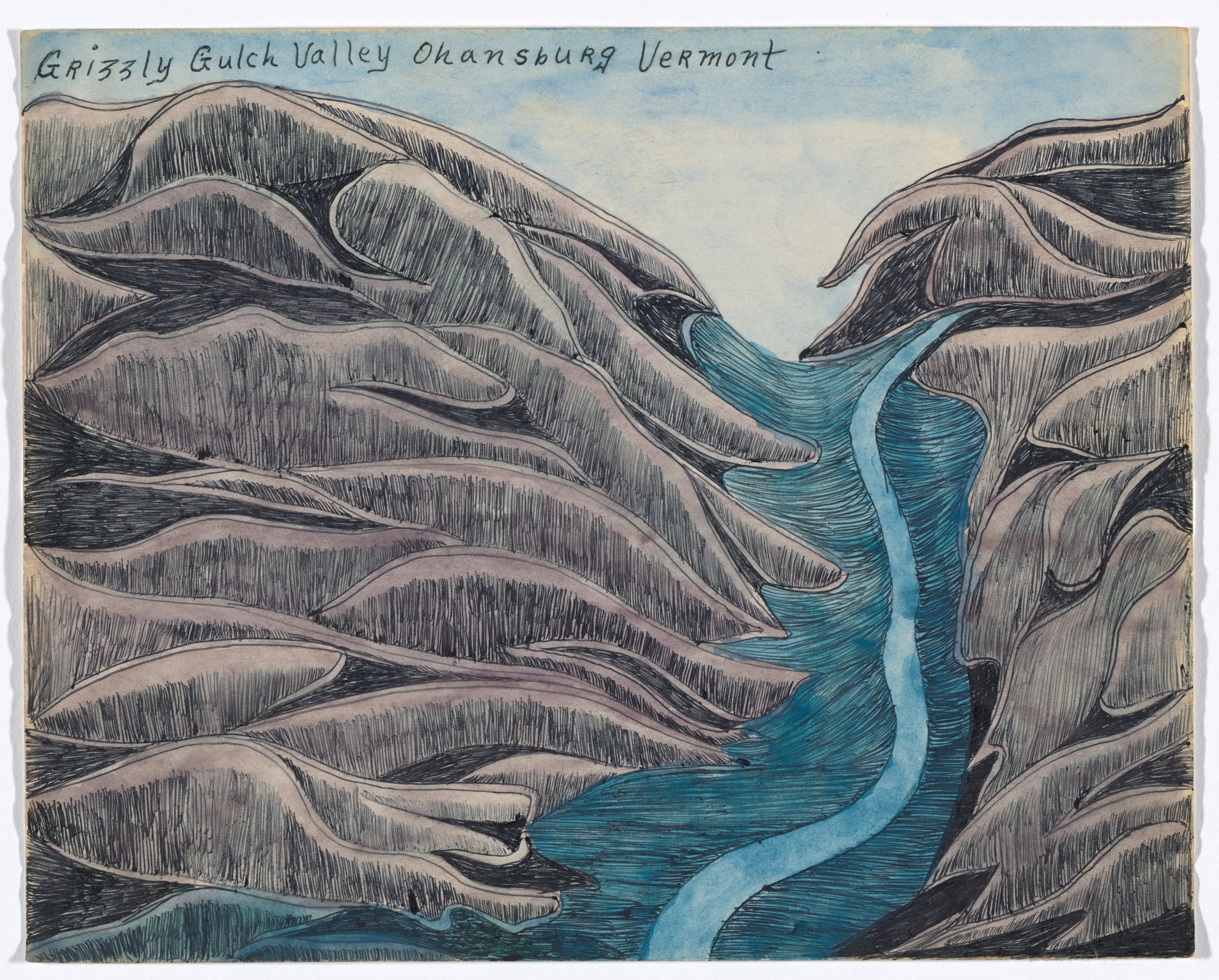

Most came in the form of dreamy landscapes, tethered equally to the natural world and the artist’s own fantastical one: scalloped mountains and pristine pools of water, forests that look like heads of romanesco, and winding roads that disappear into the horizon line. A sense of yearning pervades it all.

The old adage about the Velvet Underground—that only 10,000 people bought their first album, but that every one of them started a band—also applies to Yoakum. Not many people saw his drawings, but those who did came away as immediate and lifelong fans.

That was certainly the case with Roger Brown, Gladys Nilsson, Jim Nutt, Karl Wirsum, and Ray Yoshida—all members of the influential group of Chicago Imagists, the Hairy Who, who were among Yoakum’s most ardent admirers since meeting the self-taught artist in 1968. (Brown would later compare their discovery of Yoakum to Picasso’s discovery of Henri Rousseau.)

Now, thanks in large part to significant loans from that group, others will get the chance to fall in love with Yoakum’s work, too. A major survey of the late artist’s output—the largest ever mounted—is on view now at the Art Institute of Chicago, with subsequent stops at the Museum of Modern Art in New York and Menil Collection in Houston planned for October of 2021 and April of 2022, respectively.

Joseph E. Yoakum, Waianae Mtn Range Entrance to Pearl Harbor and Honolulu Oahu of Hawaiian Islands (1968). Courtesy of the Art Institute of Chicago.

“Jim [Nutt] once told me, “The only reason I can figure that Yoakum doesn’t have greater visibility is that he doesn’t have a weird backstory,’” recalled Mark Pascale, curator of prints and drawings at the Art institute and an organizer of the show.

“Yoakum,” Pascale explained, “was just a regular person.”

Well, sort of. The artist may have lived a rather regular life, but that’s not how he told it. Yoakum had a habit of fabricating stories about who he was and where he’d been. He was a full-blooded Native American, he told some (or a “Nava-joe” Indian, as he put it); he had a dozen brothers and sisters, he told others.

What we do know is that Yoakum, an African American, was born in Ash Grove, Missouri in 1891. He left home at nine to join the circus, and spent the next 10 years of his life traveling throughout the United States and, eventually, Asia, with various acts. In 1918, he enlisted in the army, through which he was stationed in Canada and then Europe.

Roughly 40 years later, after multiple failed marriages, he settled in a storefront apartment on Chicago’s South Side. It was there that he first began showing his work, hanging drawings in the window. And it quickly became clear that all the travels of his youth had a demonstrable influence.

Joseph E. Yoakum, American Zeppolin Flight from New York City to Paris France in Year 1939 (1969). Courtesy of the Art Institute of Chicago.

Yoakum’s drawings were almost always captioned with specific (and often playfully misspelled) names—so specific that you’d assume they were based on places he’d actually been to.

“Mt Baykal of Yablonvy Mtn Range near Ulan-Ude near Lake Baykal of Lower Siberia Russia E Asia,” reads one.

“The Open Gate to the West in Rockey Mtn Range near Pueblo Colorado,” says another.

Whether the artist had ever been to these places is unknown, and because of his penchant for stretching the truth, we may never know. But when it comes to his work, that may not be relevant.

By his own assertion, Yoakum accessed these places through a process that he called “spiritual enfoldment.” The phrase was drawn from the literature of Christian Science (Yoakum was a devout believer) and was used by the artist to describe how he used art to locate memory.

“He’d make the drawing, he’d have a spiritual enfoldment, he would recognize where the place was, and then he would label it,” Pascale said.

Joseph E. Yoakum, Mt Baykal of Yablonvy Mtn Range near Ulan-Ude near Lake Baykal of Lower Siberia Russia E Asia (1969). Courtesy of the Art Institute of Chicago.

There’s a common misconception, given the Imagist’s interest in Yoakum, that he had a great deal of influence on their work. And it’s not hard to draw a line between their brand of representation and his own. But that’s not quite right, explained Pascale. Nutt, Nilsson, and the other Imagists were almost fully formed as artists by the time they discovered Yoakum in the late 1960s.

If there was one thing that the movement’s members found in Yoakum’s work, though, it’s an interior picture.

“[The Imagists] were all trying to find their way as artists,” said Pascale. “They were looking for this place inside of themselves that was unique. With Yoakum, there it was—this guy found it.”

In a sense, it was the only thing Yoakum had. By the time he made his drawings, he was estranged from his children and had outlived all his ex-wives. He was alone.

Joseph E. Yoakum, Mt Cloubelle Jamaca of West India (1969). Courtesy of the Art Institute of Chicago.

“My takeaway, from all the years I’ve spent thinking about it, is that the landscape drawings that Yoakum made are a picture story of his life,” said Pascale.

“They are his self-portrait, his autobiography. It’s like 10 years at the end of his life spent making a visual diary of where he was, where he had been, and where he had hoped to go, where he felt most excited and comfortable, and where he felt he lived the most.”

“Joseph E. Yoakum: What I Saw” is on view now through October 18, 2021 at the Art Institute of Chicago.