Photo: maría josé/Flickr.

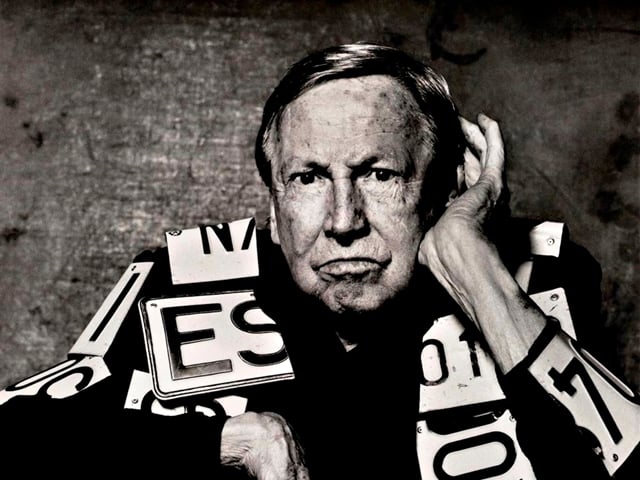

Robert Rauschenberg.

via Flickr/Kasia Wyser-Pratte.

On Friday, August 1st, a Florida judge granted Robert Rauschenberg’s accountant and two other longtime associates $24.6 million in fees for overseeing the artist’s estate—more than 60 times what Rauschenberg’s foundation deemed reasonable. “The amount awarded certainly gives new meaning to the phrase ‘friends with benefits’, when an artist’s pals are so richly rewarded,’’ said Thomas C. Danziger, an art lawyer who wasn’t involved in the multiyear court battle, in an e-mail.

Rauschenberg died in 2008, at age 82. The three trustees of the Robert Rauschenberg Revocable Trust, which was founded in 1994, had originally sought a fee of $60 million. At trial, they dialed back their request to between $51 and $55 million. The foundation, the prime beneficiary of the trust, argued that a total of $375,000 divided among the three was fair.

The court decision could prompt more artists to specify trustee fees in trust documents, Danziger said.

Christopher Rauschenberg Responds

Christopher Rauschenberg, the artist’s son, is chairman of the Rauschenberg Foundation, which provides residencies to artists on Captiva Island, Florida, and makes grants to arts and environmental organizations, among other endeavors. He was disappointed by circuit court judge Jay Rosman’s decision. “As we have said all along, we believe this case is a simple matter of evaluating the value of the services by the trustees, which we consider to be modest and not meriting an amount of this magnitude,’’ he said in a statement.

Robert Goldman, a lawyer who represents the foundation, was asked in June whether Rauschenberg would be turning over in his grave given the trustee demands. “Turning over is mild,’’ Goldman said in a video interview with the News-Press of Fort Myers, Florida. “He probably would come out and choke a few people.’’

The trustees are Darryl Pottorf, an artist who assisted and lived with Rauschenberg for over 25 years; Bennet Grutman, the artist’s accountant for 18 years; and Bill Goldston, a Rauschenberg business partner with a fine art–print publishing company. Their lawyer, Michael Gay, didn’t return an e-mail seeking comment. As they had already split $8 million in fees, the judge ordered that they were entitled to another $16.4 million, totaling $24.6 million. Their accomplishments on behalf of the trust included developing and executing a plan to withdraw Rauschenberg work from the market when he died, “to prevent a decline in value from speculators or collectors flooding the market with his art,’’ the judge wrote. Rosman cited appraisals stating that the value of assets soared from $606 million in 2008 to $2.2 billion four years later. While the rising art market and Rauschenberg’s talent were “contributing factors” in the appreciation, the judge ruled that the trustees’ performance played a key role. “The court finds that the trustees made very good decisions and rendered very good service,’’ Rosman wrote.

An Hourly Rate of $40,000

Laird Lile, a Naples, Florida, estate lawyer who was paid $23,643 by the foundation in the year ending in May 2013 (according to its tax return), had a different take. He estimated in a May 2013 affidavit that the Rauschenberg trustees worked a maximum of 1,500 hours, so their initial demand of $60 million assumed an hourly rate of $40,000. The $5.7 million he said they’d paid themselves from the trust at the time was “grossly excessive.” While acknowledging Grutman’s accounting background, he said the trustees generally didn’t have relevant experience or regularly participate in the trust’s administration, instead hiring “an army of professionals” without reviewing their work. According to press accounts of the trial, Christopher Rauschenberg testified that he expects to insure the estate for $550 million or less next year, casting doubt on the trustees’ appraisals.

The foundation spent $773,000 on legal fees and services, according to the tax return. With 21 witnesses and over 300 exhibits, the trial may have been even more expensive. A year ago, Christopher Rauschenberg was quoted in the New York Times saying, “If a judge says $60 million is fair, we’ll put it behind us and continue with the charitable stuff.” But on Friday, Rauschenberg said in a statement that the foundation is reviewing its legal options. Why? “Taking some time to review the decision thoroughly and to consider what’s best for the foundation is just common sense, and what our attorneys have advised,” a foundation spokesman said in an e-mail to artnet News.

“Our goal is to ensure that my father’s estate benefits his foundation, not the trustees who have already paid themselves millions of dollars,” Christopher Rauschenberg said. “It is our hope that we can put this matter behind us quickly, and get back to our good work at the intersection of art and issues.’’