Remember when, seemingly overnight sometime during those first few weeks of quarantine, companies shoehorned uplifting messages of solidarity and hope into their TV ads, without ever neglecting to peddle their products?

“We’re here for a reason, and it’s bigger than selling cars,” began a Ford commercial that otherwise was just a Ford commercial.

“Now’s the time for us to show off our strength,” a Michelob Ultra ad inexplicably declared.

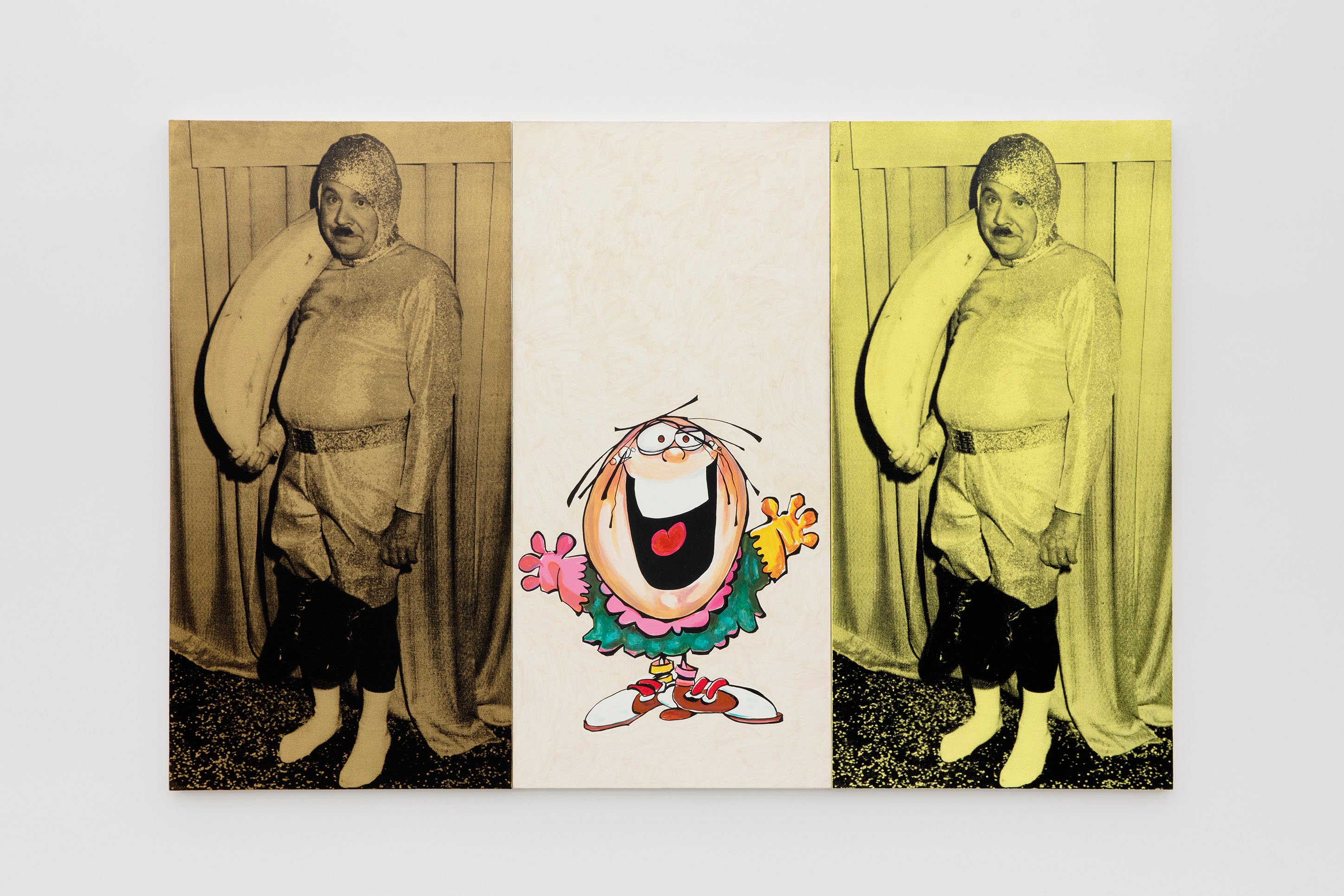

For pop appropriationist Julia Wachtel, who for four decades has been mashing up mass-media images on painted canvases, the discordant tone wasn’t new.

“That’s the COVID advertisement—which is what advertising has always been,” she tells Artnet News.

After filming snippets of commercials, reality shows, and other bits of TV, the artist created a series of short videos exaggerating this tonal tension to trippy, often humorous effect.

In one, footage of a NASCAR pit stop is intercut with shots of an electric toothbrush cleaning a corn cob. In another, a low-budget bible commercial is set to polka music.

The films—her first stab at the medium—will premier weekly on Thursdays on Perrotin gallery’s Instagram. (Wachtel’s work is also included in “The Secret History of Everything,” a group show on view at the gallery’s New York location.)

They’re short and lo-fi and have a distinct, one-step-forward, two-steps-back rhythm. They’re silly, but they’re still underscored by a languid, late-capitalist sadness—like when you find yourself watching informercials in the middle of the day.

In short, if Wachtel’s paintings were to come to life, they’d look a lot like this.

And that makes sense, considering their origin. Not long after quarantining at her home and studio in Connecticut, Wachtel ran out of the custom-made canvases she uses for her painted work. So she decided to try her hand at video.

The process was humble. In a habit she likens to fishing, Wachtel would turn on the TV and simply started surfing, using her phone to record little clips along the way.

After she had reeled in enough material, she would load it into iMovie and start experimenting. Eventually she graduated to Adobe Premiere, but was sure to maintain the sketch-like quality—a balance she learned to strike with her painting.

But the formal logic of painting is not the one through which she thinks and talks about the works.

“I listen to a lot of hip hop and rap and have since 1979 when the Sugarhill Gang came out with the first rap song,” she says, citing Kendrick Lamar as a particular hero.

“If you think about scratching or sampling and the building of overlapping layers of beats and melodies, there is a visual equivalent. For me, that’s very inspirational.”

There’s another layer between the canvases and the videos too, one that the artist is still reconciling.

Through the act of painting, Wachtel says, she’s undermining the ocean of images from which her material comes.

“I’m extracting out of that, and locating images in history. They become objects that are made at particular moments. They’re physical things that will stay in their current form. It’s about making static something that reflects a condition that is fundamentally time-based.”

But making videos is to enter back into the information flow. It’s as if, after a fishing expedition, she’s throwing her catch back in the water.

“I’m swimming with the devil now.”