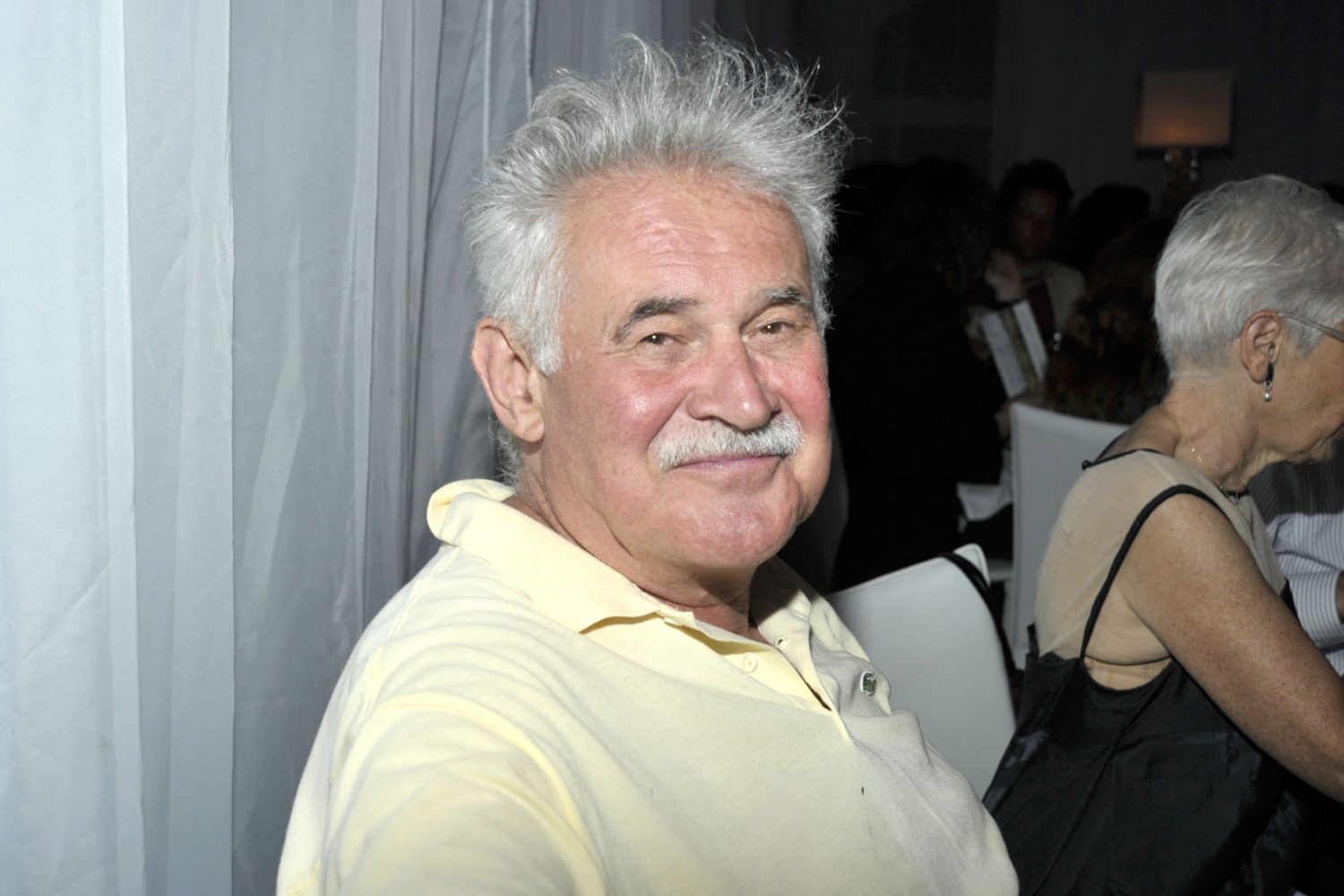

The American artist Keither Sonnier has died at age 78 after a long illness. Known for his sculptures that often entangled neon tubes with wires and other unusual materials, Sonnier became a key figure in the late 1960s artistic movement of postminimalism. He was one of the first artists to integrate light into his practice.

Sonnier’s studio shared news of the artist’s death on July 18 via social media Sunday evening.

Sonnier was born in Mamou, Louisiana, in 1941 where he grew up until he moved to Paris for a stint, and then returned back to the US to attend Rutgers University in New Jersey. He moved to New York after graduataion and quickly became a fixture in the city’s lively countercultural art scene. He made little money at the start, but his work flourished alongside friends such as the sculptors Barry Le Va and Lynda Benglis.

Installation view: “Keith Sonnier: Until Today,” Parrish Art Museum, Water Mill, New York, July 1, 2018–January 27, 2019. Photo: Gary Mamay.

Sonnier went on to become known, alongside a group of artists including Richard Serra and Bruce Nauman, for breaking from modern artistic forms of sculpture and pushing new boundaries with then uncommon materials. But Sonnier did not experience that same fast-track to success as many of his peers. In 2018, he received his first institutional solo show in three decades at the Parrish Art Museum in Watermill, New York. The late breakout moment was accompanied by shows at the Dan Flavin Art Institute in Bridgehampton and the Tripoli Gallery in Wainscott.

“I think that early investigation of any kind of materials as [a] source was probably quite important; to realize that anything could be considered art, as long as you could somehow control its manipulation or its content, or the suggestion of content,” he told Parachute Magazine about his early career and approach to materials in 1977, according a recent review in the Observer.

Moving from his early freestanding and wall-based works, which were often characterized as “anti-high art” in those years, Sonnier began to take on increasingly ambitious projects which would become public landmarks. Few will forget his temporary light work that washed Mies van der Rohe’s Neue National Galerie in Berlin in 2002 in red, yellow, and blue neon light, creating a new parameter around the largely glass building. In 2004, Sonnier made one of LA’s largest public installations, Motordom, when he light up Thom Mayne’s Caltrans District 7 Building with incandescent red and blue.

And at Munich Airport, Sonnier’s nearly one-mile-long Light Way installation still accompanies travelers as they commute through its moving walkway in terminal one.

“The difference with Keith is that he has a willingness to expose himself to experimentation that a lot of his peers lacked,” curator Jeffrey Grove, who worked on the artist’s seminal show “Until Today” at Parrish Museum, told Artnet News. “And that’s not a lack of rigor, that’s a confidence… a kind of quirky confidence that allowed him the freedom to expose himself to nontraditional materials that a lot of artists of his generation weren’t doing at the time.”

Despite falling ill, just last year Sonnier opened an energetic new show at Kasmin in New York of recently made works based on early sketches, ‘titled “Louisiana Suite.” A presentation of Dia’s acquisition from Sonnier, Dis-Play II from 1970, is set to go on display in 2022. It features a room-sized installation that includes foam rubber, fluorescent powder, strobe and black lights, as well as neon and glass.