An important moment in the ongoing push for racial equality has been immortalized by artist Kerry James Marshall, who on Thursday unveiled a monument in Des Moines, Iowa, to the pioneering group of African American lawyers who founded the National Bar Association. The sculpture stands 30 feet tall, weighs nearly 25 tons, and is clad in black manganese ironspot brick.

“I actually thought this was never going to happen,” Marshall told artnet News. He was first asked to create the memorial back in 2006, but because of difficulties obtaining funding and an approved site for the memorial, the project lay dormant for a long period. But while Marshall thought the monument was dead, there were folks behind the scenes at the National Bar Association and the Greater Des Moines Public Art Foundation working tirelessly to ensure the project would come to fruition.

“It was a monumental journey,” Marshall said, riffing on the work’s title, A Monumental Journey. “It took us 12 years to get here, but we did arrive.”

The timing now seems fortuitous: In the wake of increased calls to remove Confederate monuments, there has also been a movement to erect new ones honoring the accomplishments of African Americans and other minorities whose contributions to US history have all too often been overlooked.

Kerry James Marshall, A Monumental Journey. Photo courtesy of the Greater Des Moines Public Art Foundation.

The piece takes the shape of two massive African talking drums stacked precariously atop one another, seemingly on the verge of toppling. Used by the West African Yoruba people for communicating over long distances, the talking drum was so named for its resemblance to human speech.

“There are a lot of languages that are tonal, where the inflection or the sound is used to carry a lot of the communication,” Marshall explained. “The talking drum has an hourglass-shaped form that has tension bands around it. Those are used to vary the pressure around the drum head, which is like a diaphragm. Varying the tension makes the drum vibrate at different pitches, much in the same way as our vocal chords. That’s how information can be communicated over long distances because that tonal inflection is like speaking.”

The sculpture’s form—recognizably African but eschewing stereotypically bright colors and patterns—represents the importance of communication between groups of people, and both the need for and the difficulty in achieving a balanced justice system.

“The legal system is supposed to be organized to bring justice, but it’s never a simple or straightforward matter. It’s always more dynamic and more complicated than it seems to be on its face,” said Marshall, who has inscribed the base of the sculpture with the names of the National Bar Association founders.

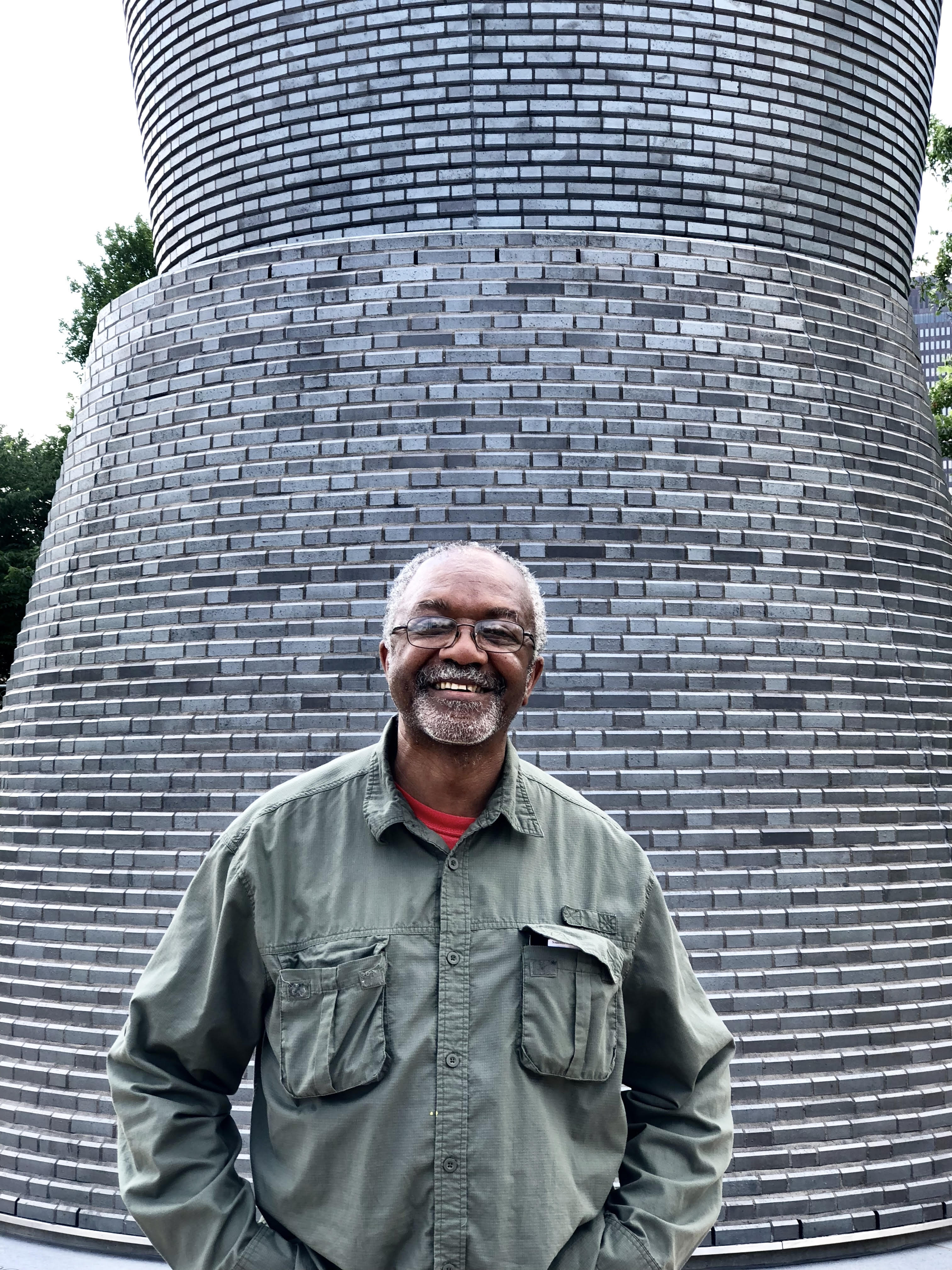

Kerry James Marshall with A Monumental Journey. Photo courtesy of the Greater Des Moines Public Art Foundation.

In 1925, facing discrimination from the American Bar Association other legal organizations on the basis of their race, 12 black lawyers—11 men and one woman—established the National Bar Association in Des Moines. Its mission was “to strengthen and elevate the Negro lawyer in his profession and in his relationship to his people.”

Now the oldest and largest legal association to primarily serve black lawyers, the National Bar Association represents members in the US, Africa, the UK, Canada, and the Virgin Islands. The monument, which gives overdue recognition to this important chapter in Iowa history, is the brainchild of local judge Odell McGee, a former president of the Iowa chapter of the National Bar Association.

He conceived of the idea of an artwork memorializing the group’s founding in 2002 while speaking with fellow past president Evett L. Simmons at the organization’s 75th-anniversary celebration. In 2006, McGee approached the Greater Des Moines Public Art Foundation about making his dream a reality, and to help find the right artist.

Kerry James Marshall with A Monumental Journey. Photo courtesy of the Greater Des Moines Public Art Foundation.

The two groups considered Martin Puryear but ultimately approached Marshall later that year. “I had never heard of the National Bar Association,” Marshall admitted. “Unless you’re in the legal profession, it’s not something you would just know.” Nevertheless, he didn’t hesitate to get involved: “It’s always nice to have lawyers on your side,” he joked.

“When you get the opportunity to design something that is supposed to commemorate, memorialize, or recognize an important achievement, it’s always hard to figure out what kind of form that thing could take,” Marshall added. “The artist comes in like a hired gun from out of town—somebody you hope has a different perspective.”

Soon enough, the design came together, but fundraising efforts fell short, delaying the project, even after the artist personally fronted the cost of a costly water feasibility study. Further complications arose when they had to abandon the original project site in 2011. The foundation officially took over the project from the bar association two years later, securing the final location for the work in 2015 and raising $1 million for its completion.

Kerry James Marshall, A Monumental Journey. Photo courtesy of the Greater Des Moines Public Art Foundation.

A groundbreaking took place in November 2016, and fabrication began, finally, last year—in some ways, the most challenging part of the whole process. “Nearly every angle of the form is different, so you can’t just mass produce one brick and make that work. Every one of those bricks had to be cut by hand to make that cylindrical form consistent,” said Marshall. “The team of masons who they had working on the project was just masterful.”

In some ways, the prolonged timeline for A Monumental Journey is only fitting: The memorial’s intermittent progress mirrors the long, difficult struggle for racial equality—still ongoing almost a century after a brave group of African American lawyers banded together to form a bar association of their own.

“These people were able to achieve something that made a difference in the lives of a lot of people,” Marshall said. “The organization should live on in the memories of people way past our time… The more we remember, the better.”

Kerry James Marshall’s A Monumental Journey is on view along the Principal Riverwalk at Hansen Triangle Park, Grand and 2nd Avenues, Des Moines, Iowa.