Among the modern mega-appliances of the digital age—Uber, Google, Facebook, and the rest—the crowdfunding site Kickstarter is one of the indiest, and the most charmingly quirky. It was co-founded in 2009 by Perry Chen, a musician-turned-conceptual artist who bounced around a series of side gigs (from day-trading to working in a restaurant to founding an art gallery) until he realized there had to be another way to fund creative projects.

Since then, Kickstarter has become the place where artists and inventors can make their dreams a reality through one simple formula: create a persuasive pitch (for a movie, a board game, a “Dr. Who”-themed rap album) and some merch for rewarding funders, and watch the money roll in. (Kickstarter takes a five percent cut if a project is funded.) It’s one of the few companies that still fulfills the original ‘90s-era promise of the Internet as a zone for weirdos and brainiacs around the would to unite and find common cause.

Today, as Kickstarter celebrates the 10th anniversary of its founding, it has also grown into something of a gentle behemoth. It has raised $1 billion for games alone, has famously outpaced the NEA as America’s top cultural funder, and become a widely known player in the art world, providing budgets for public-engaging projects by artists from Ai Weiwei to Lucy Sparrow to Pope.L. It has also helped bring head-turning art memes to life, like Stuart Semple’s “Black 3.0,” a contender for the blackest paint in the world.

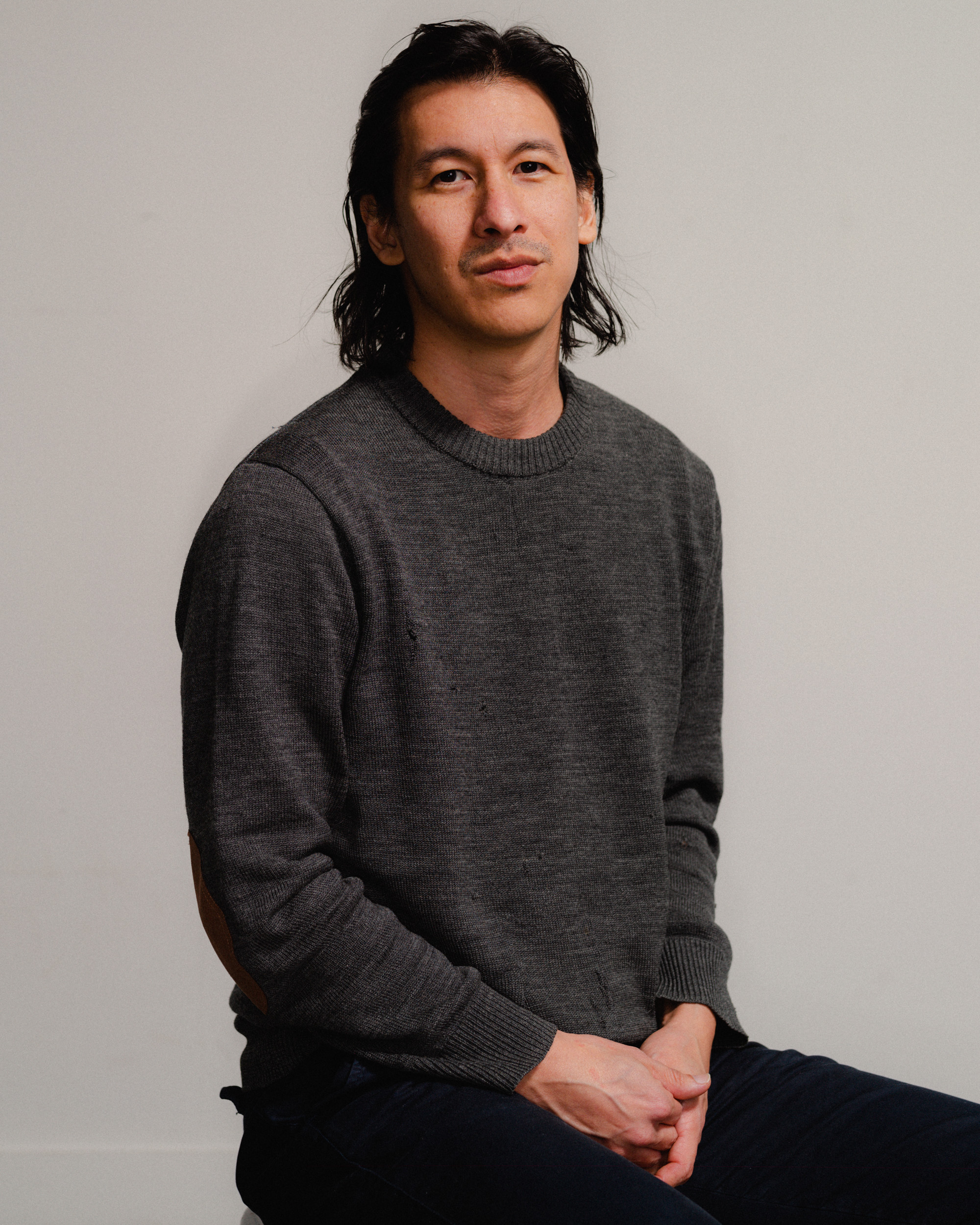

Chen, a native New Yorker who spent his formative years as a musician in New Orleans, is not your typical tech founder in the mold of Silicon Valley’s elite—instead of angling for world domination, he has spent much of the past decade searching for meaning and self-actualization. This has led him to bounce around inside the Kickstarter universe as much as he did before. In 2014, he left the CEO role to focus on his own high-concept art projects, then returned in July 2017 to seize the reigns from his cofounder, Yancey Strickler. Last month, less than two years later, he stepped down again from that role, retaining the title of chairman.

It has not, in other words, been all smooth sailing. But Kickstarter, as a company, is a feeler, as self-doubting, anxiety-ridden, and idealistic as the creators it was designed to support. In the first installment of a two-part interview to mark the 10th anniversary, artnet News’s Andrew Goldstein sat down with Chen in the company’s cavernous Greenpoint headquarters—a former pencil factory—to discuss his road to inventing Kickstarter, his own artistic pursuits, and why his company is less a solution to a problem and more a signal flare for help.

This week you’re celebrating the 10-year anniversary of Kickstarter, which is an extraordinary accomplishment—especially for an online startup that was founded by an artist who didn’t really even know how to code.

I had no coding experience. I still can’t code.

What you did have, instead, was a crazy, almost-utopian idea about how culture can be supported by its fans. Today, Kickstarter has become a beacon of hope for artists who are struggling to realize their visions in a ruthless capitalist climate. You obviously understand their plight from the inside, as an artist yourself. Could start by telling me how you first found yourself in the art scene?

My entrée into art was through music. I grew up in here in New York City, and I was raised listening to hip-hop and New Wave stuff. I later moved to New Orleans and started making music. Then 18 years ago, I co-founded an art gallery in Brooklyn, Southfirst, which makes it one of the oldest Williamsburg galleries at this point.

That was a highly respected gallery, which you started with the art critic Maika Pollack, and which just closed down last year.

I was there for half a year in the beginning, and then she did it for 18 years, so she was the force. Years later, after Kickstarter had been around for four and a half years, I stepped down as CEO to work on art, specifically research-based conceptual stuff. I was interested in making art that was about trying to understand the world that we’re moving into, which in my mind is defined by complexity. I feel like technology often gets used as a synonym for complexity, but to me the real complexity is what’s underneath the technology. We’re animals that slowly evolved from being hunter-gatherers, but the things that we’ve been forced to deal with have become so abstracted and opaque. When finance fails us time and again, it’s because they create some hyper-complex instrument that even the people who regulate it don’t understand, so it ravages us for years before anybody figures out what the hell is going on.

A photo from Computers in Crisis, 2014. Courtesy of www.computersincrisis.com.

This reminds me of one of the first art projects you undertook after you first stepped down as CEO in 2014, an exploration of Y2K called “Computers in Crisis” that you debuted at the New Museum.

When I left that was the first work that I couldn’t wait to do. It was about all these themes but through the prism of an event that was the biggest story in the world for several years, remember? “Y2K is coming.” It was a massive cultural moment, and a real existential moment. What if the all computers, which had become entrenched into every facet of our world, just stopped? It was a perfect crystallization of complexity. Nobody was able to step back and say how the whole would react.

The art business is definitely one area of culture that embraces complexity, since you have collectors who are interested in buying things to put in storage so they can flip it a later time, or leverage it as a financial commodity. The way the business side of art operates is almost Byzantine. Did any of this impact your thinking when you came up with the idea for Kickstarter? What was the problem that you set out to solve through technology?

I’ve never worked in technology and I’ve never worked in an office context before. So Kickstarter came more from the thought that, if this existed, I would use it. My friends would use it. Among all the people I know who do different creative endeavors, one common thing we often share is the need for money.

Around the time when I first had the idea, in 2001, I was living in New Orleans and working in music. There was all this Napster stuff going on and people were talking about what musicians and the industry can do now that music has gone digital and people are stealing it, getting it for free. All this revenue seemed to be disappearing, but the music companies were probably taking too much of it begin with—so the question people kept asking was, “How do we continue to monetize things?”

I realized this is a very important question because, when you monetize creative work, you get the money to potentially make it again. But that’s too far down the road. The first thing we have to ask is, “How do you get the money to make it in the first place?” Everybody was just skipping over that step.

There are plenty of tremendously important creative works that didn’t have a way of being monetized until years, or decades, after they were made. Just look at performance art in the 1960s and ’70s, or, for that matter, any kind of art by people who were historically marginalized from the mainstream culture.

Not everybody has the opportunity to go to the extremes that you need to go to when society says what you do has no commercial value. But if you are able to do that, and able to lead the life that requires, then I think you’ll often be standing there as a master craftsperson when people start paying attention, 10 years later or 100 years later.

A photo of Lunar, 2014. Courtesy of Perry Chen’s website.

It’s interesting that the art you make yourself doesn’t really have a clear way of being bought and sold, like Lunar, your 2014 immersive installation work in Mexico City’s Teatro Santa Cecilia that filled the theater with debris, spotlights, a projection of the full moon, and the rumbling sound of a generator. It was a pretty ambitious project. What did you get out of it?

It was a four-day installation I did in a former Mariachi theater. It was a lot of work for four evenings, and now I have some not-great video and some good photos to show for it. But that’s okay. It forced me to think about what I do. I try to be very medium-agnostic, meaning that I’m working with the thread of an idea and I want to pour it into whatever mold of media feels right for it, or whatever venue is available to me. And afterward, there are the various ephemera that come out of it, like the photos.

Same with my Y2K project—now there’s this archive of 200 books about Y2K that I tracked down, and it’s the only existing one in the world. Then I did a one-evening panel at the New Museum interviewing people who had been deeply involved in Y2K in front of an audience, asking a lot of questions that hadn’t really been asked before, and now that’s a moment that’s just gone, even if there’s video of it.

I am doing what I’m doing not to create an object to be bought and sold, but because I want to do something, even if, like with the New Museum project, only 120 people experience it in person. But I also want to find a way that I can share material elements of my work in non-scarce ways so people can engage with it.

Pins are in on Kickstarter. Screenshot by Andrew Goldstein.

If you scroll through the Kickstarter Arts section, one thing I’ve noticed is that there are a lot of campaigns to create illustrated tarot cards and quirky enamel pins.

It’s a trend.

I can understand why these would be popular, because they’re incredibly accessible and there’s a clear thing a funder can get out of supporting it: an enamel pin. But, of course, the marquee projects that Kickstarter Arts has supported are the exact opposite of the enamel pins: sweeping artworks like Ugo Rondinone’s colorful rock sculpture in the Nevada desert, Ai Weiwei’s public-art sculptures around New York City, and the For Freedoms nationwide billboard project. What is Kickstarter’s role in helping artists make work, and what kind of work do you hope Kickstarter helps bring into the world?

With public art, it’s never one artist on their own—they’re engaged with some municipality, working toward getting something in front of people. It’s a good idea to start to telling people the story of the project in advance. They may need a little bit of supplemental money—you always do—or they just want to start engaging with the public early on. That’s what happened with the Statue of Liberty. The French told New York, “Hey, we’ve got a statue for you,” and New York had to be, like, “Cool, we’re going to build a base for it.” So a committee for creating the base of the Statue of Liberty basically put ads in the New York papers advertising that if you give a dollar, you’ll get a little miniature of the Statue of Liberty, and if you give five, you get a larger miniature of the Statue of Liberty. And New Yorkers funded the base in that way.

Mozart also funded at least one concerto by asking dozens of people for small amounts—not the Medici patron model, with one person who has a big purse—in exchange for a signed copy of the concerto. Many of Walt Whitman’s first editions have pages and pages of names listed in them, and those were also people who helped him fund them through small amounts. He called them “subscribers,” but they were very much one-off patrons who helped to make that one book.

There is a history of patronage being more distributed and democratic that industry kind of made us forget about for a long time, until the point when business models started being disrupted, alternative sources of capital were so desperately needed, and the stage was set for something like Kickstarter to exist.

You mentioned the Medici, and it’s interesting that you were in Florence, home of the Medici, when you were hit with the inspiration to write your famous “existential kickstarter” memo that set the company on the path to becoming a Public Benefit Corporation in 2015. What gave you the idea?

My sister married a Florentine, so I was staying in a small apartment across the street from his mother’s house for a week. I had left Kickstarter at this point and I was probably a year into my full focus on my studio work. But this was something in the back of mind that I really needed to get down on paper. It went back to the question of, why are we doing this? We didn’t come into this as businesspeople looking for a vehicle to make money, we did it to help creative projects come to life, we value culture, and we don’t ask it to justify itself. It can never do that. It can’t be quantified.

Like anybody, if I can make some money along the way, I’m happy to do it. But I won’t ignore our values. And I’m not saying that’s been the case, you know. We pretty much poured all the money back into the business. We’re not anything like what people think when they think of tech founders—we’re not super-wealthy people. This building you’re in absorbed every dollar we made in the first five years.

At that point I wasn’t running the company day-to-day—I was chairman of the board, putting in a day a month or something. I was feeling really detached. Were we running Kickstarter because it exists, just to perpetuate it? We’re not the old steel mill—it’s not like the town would shut down if we left. There has to be a sufficient impact we can make to justify the time and energy and effort that we ask of people.

Ai Weiwei’s Gilded Cage (2017) was in part funded by Kickstarter, raising more than $90,000 from 883 backers. Courtesy Public Art Fund.

So this led you to transform Kickstarter into both a Public Benefit Corporation and a B corp, a special designation for a company that meets high standards for transparency and social and environmental sustainability. It makes sense, because sustainability is such a key part to Kickstarter’s allure, where its crowdfunding function can allow creatives to do projects that they might not have been able to do otherwise, creating an equilibrium between demand for a project and its ability to exist. At the same time, not all artists are on equal footing when it comes to creating Kickstarter campaigns. On one hand, you have the Kickstart Art projects with Ai Weiweis and the Ugo Rondinones, who get special promotion and visibility on the platform, and then there are the other artists whose campaigns fall into the general pool alongside the enamel pins and tarot cards. What considerations put one artist in one camp and another artist in the other?

There is no hierarchy in the sense that if you already have the audience to support your work, then that audience gets to decide if you should be able to go ahead and make it. Of course, if somebody who’s got a big name and who we admire is doing something, we’ll certainly try to attend to them. But ultimately our intent is to try to help everybody who wants to do creative work. Somebody from Ai Weiwei’s team doesn’t get to come into a room and we tell them, “Okay, here’s the real secret of how to do it.” There are no secrets. All our advice is up there on the site, from working on your narrative to working on your video to thinking about how you offer people ways to engage with your project. And we don’t see it as a competitive environment, either. It’s not like buying a vacuum cleaner.

Out of curiosity, do you think your own art projects would hit their funding targets if you put them on Kickstarter?

My Y2K project would translate a lot easier—it’s very narrative driven—than the immersive work in Mexico City, where a lot of it is about being in the room there. That said, you don’t need to use Kickstarter to raise the total amount of money you need for your project. So I might have been able to raise a couple thousand dollars for the Mexico City project.

Olafur Eliasson’s Kickstarter campaign for his Little Sun Charge solar-powered phone-chargers raised €265,448 in 2015. Screenshot by Andrew Goldstein.

The conundrum is that, while Kickstarter is democratic in some ways, in other ways it’s not. With artists like Ai Weiwei or Olafur Eliasson who have giant fanbases worldwide, many people will be willing to support pretty much anything they do—their projects are typically over-supported. On the other hand, if you’re not a famous artist, it’s more difficult to get attention, so it’s easier for someone making something concrete and accessible like enamel art pins to get funding than for someone doing a subtle poetic artwork.

It’s counterintuitive, but the best thing for everybody is that artists with large audiences use the platform, because they bring their audiences in. For example, we just had a very large film project called Critical Role—for millions and millions of dollars, which is still rare—and there are almost 90,000 people who have backed the project, and probably a majority of them are first-time backers on Kickstarter, and they have then gone on to support another quarter-million bucks to other projects.

So when Spike Lee did a Kickstarter five years ago, people said, “Why would Spike Lee do this?” And I understand that suspicion. But Spike Lee was bringing an audience that he had been building for 20 to 30 years who went on to support a lot of other independent filmmakers. So I hope people can see past an environment of zero-sum.

At the end of the day, Kickstarter is not the the answer to anything—it’s just another piece of the puzzle. We have philanthropy. We have investment. We have commerce. This is another model. I remember when people started writing articles about how Kickstarter was raising over $500 million dollars, making it more than the NEA’s budget. I worried people would use that as another reason to defund the NEA. The NEA should get more money. Our success should be seen as a sign of need, not a solution.