One of the most exciting theories in the field of ancient Egyptian archaeology just got a lot less exciting. Egypt’s antiquities ministry has announced that new scans of King Tut’s tomb show that there are no sealed-off rooms hidden in the historic burial chamber, as some experts had postulated.

“Our work shows in a conclusive manner that there are no hidden chambers, no corridors adjacent to Tutankhamun’s tomb,” Francesco Porcelli of the Polytechnic University of Turin told the audience at the fourth International Tutankhamun Conference in Cairo, as reported by the Associated Press. “There was a theory that argued the possible existence of these chambers, but unfortunately our work is not supporting this theory.”

This contradicts the results of previous tests, which had left archaeologists 90 percent certain that there were not one but two secret chambers inside the historic tomb. The antiquities ministry had called the rooms, now said to be nonexistent, potentially “the discovery of the century.”

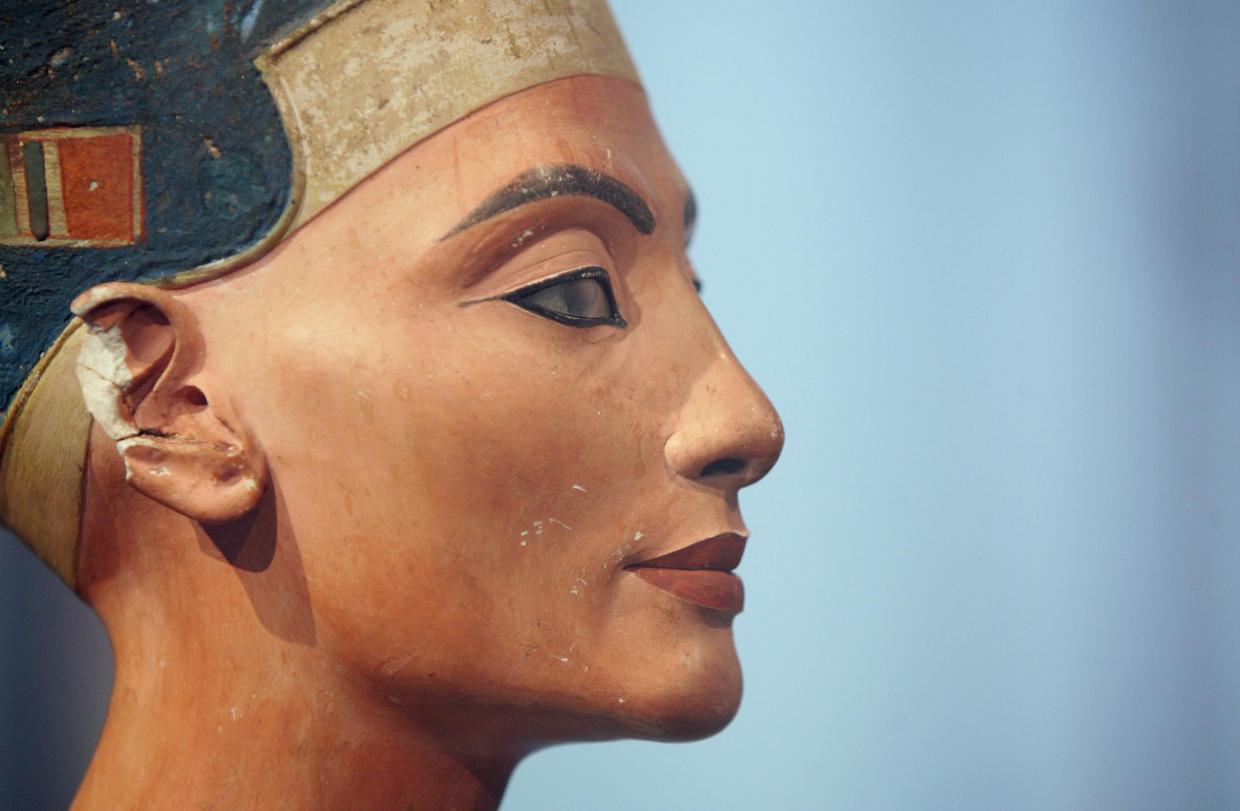

A diagram of King Tut’s tomb showing the suspected locations of Nefertiti’s tomb. Image courtesy of Nicolas Reeves.

Nicholas Reeves of the University of Arizona had rocked the field of Egyptology with the August 2015 publication of the paper, “The Burial of Nefertiti?,” in which he posited that the tomb was originally built for the burial of Queen Nefertiti and that there was evidence of sealed-off doorways into chambers that might still house her remains.

The theory was based on high-resolution laser scans of the tomb taken to create a life-size copy of the space, which appeared to show the faint outlines of two doors on the chamber’s walls. Reeves argued that Tut’s tomb was smaller than one might expect for a pharaoh because it was a secondhand burial site originally used for the boy king’s stepmother.

Archaeologist Nicholas Reeves believes this painting in King Tut’s tomb marked the closing of Nefertiti’s now-hidden burial chamber. Courtesy the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Reeves also claimed that mix of queenly and kingly iconography in the tomb’s artifacts indicated that some of them might have been originally made for Nefertiti before she became pharaoh under the name Neferneferuaten. He posited that because Tut died young, no burial site was prepared; Nefertiti’s unused artifacts were pressed into service and her tomb expanded to make room for her successor.

Archaeologists set out to test Reeve’s theory a mere month after the publication of his paper, using non-invasive radar technology. Although the initial results were promising, the tests have ultimately ended in disappointment. (On the other hand, there are, in fact, mysterious empty rooms of some sort in the Great Pyramid of Giza.)

King Tut’s tomb was discovered in 1922 by Howard Carter and has captivated the world’s imagination ever since. Some 150 artifacts from the tomb are on a world tour in the traveling exhibition, “King Tut: Treasures of the Golden Pharaoh,” on view at the California Science Center in Los Angeles through January 2019.