The infamous Abstract Expressionist forgery ring that rocked the art world is back in the headlines. Last week, a federal judge in Manhattan set a July court date to determine whether Michael Hammer, the former owner of the infamous Knoedler Gallery, which sold tens of millions of dollars worth of fake art, could be held liable for the sales.

The lawsuit has been filed by two collectors, the Martin Hilti Family Trust and Frances Hamilton White, who are suing the gallery, its parent company, 8-31 Holdings, as well as Hammer, the sole shareholder of 8-31. The trust spent $5.5 million on what turned out to be a fake Mark Rothko in 2002, and White and her then-husband bought a fake Pollock for $3.1 million in 2000.

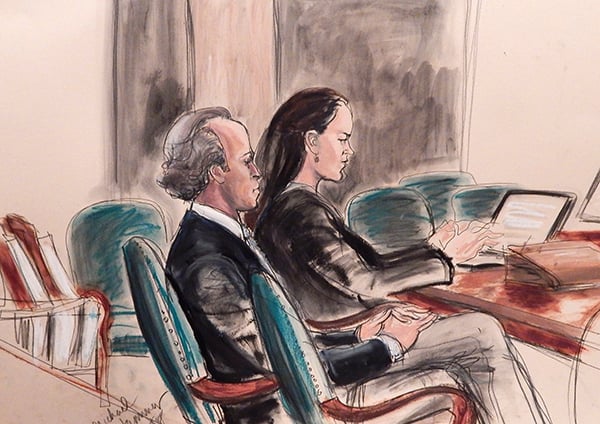

On Wednesday, Judge Paul Gardephe dismissed the plaintiffs’ claims that Hammer and 8-31 were engaged in fraud or racketeering, saying there was not enough evidence to prove he knew the Rothko and Pollock paintings were forged, the Art Newspaper reports.

But he is allowing the plaintiffs to pursue Hammer because of the porous borders between his personal finances and 8-31, which regularly funneled money from the gallery. The finances were so entwined that Hammer claimed $2 million in business expenses from 8-31 to purchase seven luxury cars, which may have been for his personal use. He also kept the proceeds after he sold two of the cars. Judge Gardephe found that a reasonable jury might see this as co-mingling between his personal and business expenses.

This work, purported to be by Mark Rothko, was forged and sold as authentic by the Knoedler Gallery. Courtesy of Luke Nikas/the Winterthur Museum.

“Generally, corporations confer on their owners limited liability, so they aren’t personally liable,” James Janowitz, who represents the Hilti family, told the Art Newspaper. But Hammer may have lost that privilege if he treated 8-31 as an extension of himself, as opposed to a separate, business entity. And if he did, he may be held liable for any fraud carried out by Knoedler.

Should both parties proceed to trial, it would be only the second of 10 connected claims to come before a jury. As of press time, the legal teams for both sides had not responded for requests for comment.

The venerable Knoedler Gallery, founded in 1846, collapsed in 2011 when it was revealed that between 1994 and 2009, the business had sold millions of dollars worth of purported Abstract Expressionist masterpieces by the likes of Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko, Willem de Kooning, and Robert Motherwell.

The worthless fakes were in fact created by a Chinese immigrant in Queens, and peddled to Knoedler by a Long Island gallery dealer named Glafira Rosales. She claimed they had belonged to a mysterious and well-connected art collector named “Mr. X.”