A high-profile forgery case involving the late American artist Leon Golub and hedge-fund manager and art collector Andrew Hall is getting its day in court. A judge recently refused to dismiss Hall’s case against an artist and her son who sold him 24 paintings purportedly by Golub that now appear to be fakes. The case is expected to head to trial in October.

Between 2009 and 2011, Hall spent $676,250 on works believed to be by Golub that belonged to Lorettann Gascard, an artist and art history professor who studied with the American artist, and her son Nikolas Gascard. (The Gascards sold other alleged Golubs to various buyers, none of whom has taken legal action.)

Andrew Hall and his wife Christine are among the world’s most prolific and prominent art collectors. They present their extensive holdings in a converted 19th-century farmhouse in Reading, Vermont, as well as at a castle formerly owned by Georg Baselitz near Hanover, Germany. Their art foundation also has a partnership with the Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art in North Adams.

After Hall bought a number of purported Golubs at auction, the younger Gascard connected with him directly. Eager to cut out the middle man, Hall jumped at the chance to add more work by the postwar artist to his collection. (Hall’s self-professed collecting strategy is to target “overlooked corners of the art world” where his budget will go the furthest, he once told PBS.)

The collector learned the trove was inauthentic when he began planning an exhibition of Golub’s work—ultimately cancelled—at the Hall Art Foundation in Reading. In 2015, he asked Golub’s foundation to take a look at the works, and they wrote back immediately to note there was no record of any of the 24 works purchased from the Gascards ever having been created.

The Legal Battle

The Gascards’ lawyers have argued that the statute of limitations for a fraud claim had passed. As a sophisticated art collector, they claim, Hall should have had the paintings examined and authenticated at the time of purchase, not years later.

District Judge Steven J. McAuliffe disagreed, noting that Hall first purchased works from the Gascards’ collection through “reputable auction houses that, presumably, make reasonable efforts to avoid dealing in forged works of art.”

The upcoming trial will consider three of the original six claims pursued by Hall: fraud, conspiracy to defraud, and unjust enrichment. (The judge found that under New Hampshire law, the statute of limitations had run out on his breach of warranty claim.)

“To prove fraud, they will have to show by the evidence that the sellers actually knew that what they were selling was counterfeit, and sold it knowing that,” New York art attorney Sam P. Israel told artnet News. “The unjust enrichment claim will mostly turn on whether or not what they bought was in fact counterfeit, and they’ve kept something that they’re not entitled to.”

Altogether, Hall bought eight Gascard Golubs at auction—through Christie’s, Sotheby’s, and artnet Auctions—and 16 directly from mother and son. (None of the auction houses, which refunded Hall, are parties to the case.) Hall’s claims now amount to $468,000, plus statutory interest and attorney’s fees.

Andrew Hall. Photo by Nicholas Richer, ©Patrick McMullan.

The Saga of the Fake Golubs

The story of how the Gascards acquired the so-called Golubs has shifted over the years. “Lorettann Gascard has given inconsistent and contradictory accounts of how she came to acquire the various works, at times saying they were gifts or purchases directly from Golub,” noted Judge McAuliffe.

Lorrettann claims to have been friends with Golub and his wife, artist Nancy Spero, who died in 2009. (The Gascards first took their ersatz Golubs to market shortly after Spero’s death.) When asked later by Hall’s foundation to provide evidence of her relationship to the couple, she furnished two letters from them, neither of which mentioned her owning any works by Golub. (The artists’ children say they do not remember meeting or hearing about her.)

Lorettann, who left her job at New Hampshire’s Franklin Pierce University after an unrelated age discrimination suit in 2015, now says that Golub once gave her a selection of works with instructions to throw them away. She claims to have held onto the paintings she was charged with discarding. Later, she says, she introduced Golub to her husband and sister-in-law, who forged their own relationship with the artist.

When Nikolas consigned the paintings at Christie’s, he originally claimed to have acquired the works “directly from the artist” or “from the artist by descent.” In a deposition, he clarified that he meant that his aunt, who had recently died, had acquired them from Golub. Nikolas said he had discovered a roll of signed Golub paintings when going through her home in Hamburg, Germany.

Those paintings allegedly included the ones Golub had wanted Lorettann to throw out, plus additional works the Gascards say must have been purchased over the years by the aunt and Nikolas’s father. (Nikolas now recalls as child hearing his father and aunt talking about wanting to invest in Golub’s work.)

Nikolas now admits to having made up titles and estimated the dates for each painting in their collection.

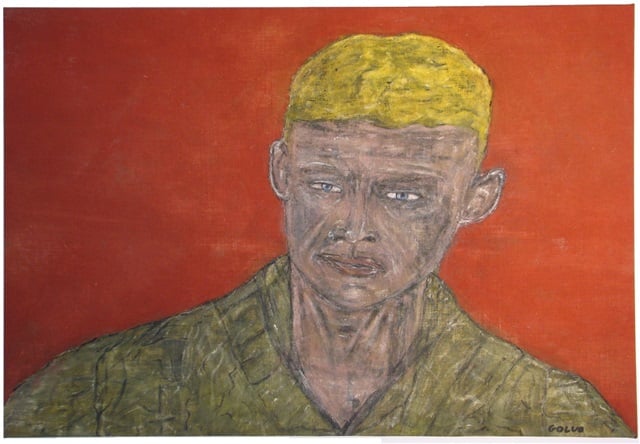

This fake Leon Golub, Two Black Heads, was purchased at Christie’s by Andrew Hall from Nikolas Gascard for $23,750. Courtesy of artnet.

A Question of Intent

So far, the Gascards have not insisted during the legal proceedings that the works are real—but they haven’t conceded they are forgeries, either. Lawyers familiar with such cases say that the outcome will hinge in part on whether the Gascards knew they were fake when they sold them.

“The question is, when they were making those things up, did they themselves believe that it was an authentic Golub? Somebody can make a history up because they want to achieve a sale, but they might still believe the painting is authentic,” said Israel.

So far, the judge seems inclined to side with Hall, who he believes “has pointed to sufficient facts which, if credited as true, would permit a jury to conclude, by clear and convincing evidence, that the Gascards knew the paintings at issue were forgeries.”

The fakes are undoubtedly sophisticated, fooling nearly everyone who came across them. Golub’s son and his former studio manager had previously seen the paintings in an informal exhibition staged by Hall for friends and family, but under closer examination, the works had clear issues in style and form that the foundation found “problematic.”

In an exhibit filed by Hall’s lawyers, Golub scholar Jon Bird describes at length Golub’s laborious process, which involved repeatedly scraping layers of paint off the canvas.

“There is no evidence of this process in any of the works examined,” wrote Bird, also criticizing “the clumsiness of the figuration, not Golub’s deliberate ‘awkwardness,’ but a crudeness in the depiction of the figure and lack of understanding of basic anatomical principles.” He determined that none of the Gascard’s paintings could be by Golub’s hand.

This fake Leon Golub, Untitled, was purchased at Christie’s by Andrew Hall from Nikolas Gascard for $30,000. Courtesy of Christie’s.

If They Aren’t Real, Who Painted Them?

Hall’s lawyers are expected to argue that the fake Golub paintings are the handiwork of Lorrettan, who studied under the older artist in the 1970s at Fairleigh Dickinson University in New Jersey. Judge McAuliffe noted that “although Hall has yet to provide direct evidence on the matter, he plainly suspects that Lorettann is the person who produced the forgeries.”

Lorettann’s auction record for her own work, according to the artnet Price Database, is $45,000 for a rust on linen work, Men With Guns, one of three of her paintings Nikolas sold in 2009 at Wright auction house in Chicago.

In a bizarre twist, Nikolas admitted he only agreed to consign a pair of the family’s Golubs to Wright on the condition that they also auction three of his mother’s works. The unexpected bidding war that followed, it turned out, was actually Nikolas under two fake names, Art Thoreau—after Franklin Pierce’s Thoreau Art Gallery, where Lorrettann was then director—and Larry Devlin, from her maiden name.

Nikolas Gascard bid under fake names to drive up the price on these two works by his mother, Lorrettann Gascard, when he consigned them at Wright. Photo courtesy of Wright.

After Hall initially filed suit in October 2016, several news outlets reported that the Gascards had gone missing, and no longer resided at their previously known addresses. They later resurfaced, initially representing themselves in the dispute.

In March, now represented by New Hampshire firm Cleveland, Waters, and Bass, the Gascards called to have the case dismissed. The mother and son claim there is no evidence they attempted to defraud anyone, despite their shifting stories regarding the suspect works’ origins. Neither the Gascards nor their lawyers responded to inquiries from artnet News.

Regardless of where the works came from, it is undoubtedly troubling that so many fake paintings could pass muster at leading auction houses and hoodwink knowledgeable collectors.

“It’s a lesson to purchasers that they should be more careful… this is a pervasive problem in the art business,” said Israel. “Because paintings trade at such high numbers, people are incentivized to make phony ones. There are a lot of artists who are very good at duplicating paintings. If they can create the appearance of provenance, then they can make a fortune.”