Tere Arcq didn’t expect anything like what she found during a 2017 visit to a collector while she was doing research for the 2018 show “Leonora Carrington: Magical Tales” at the Museo de Arte Moderno in Mexico City.

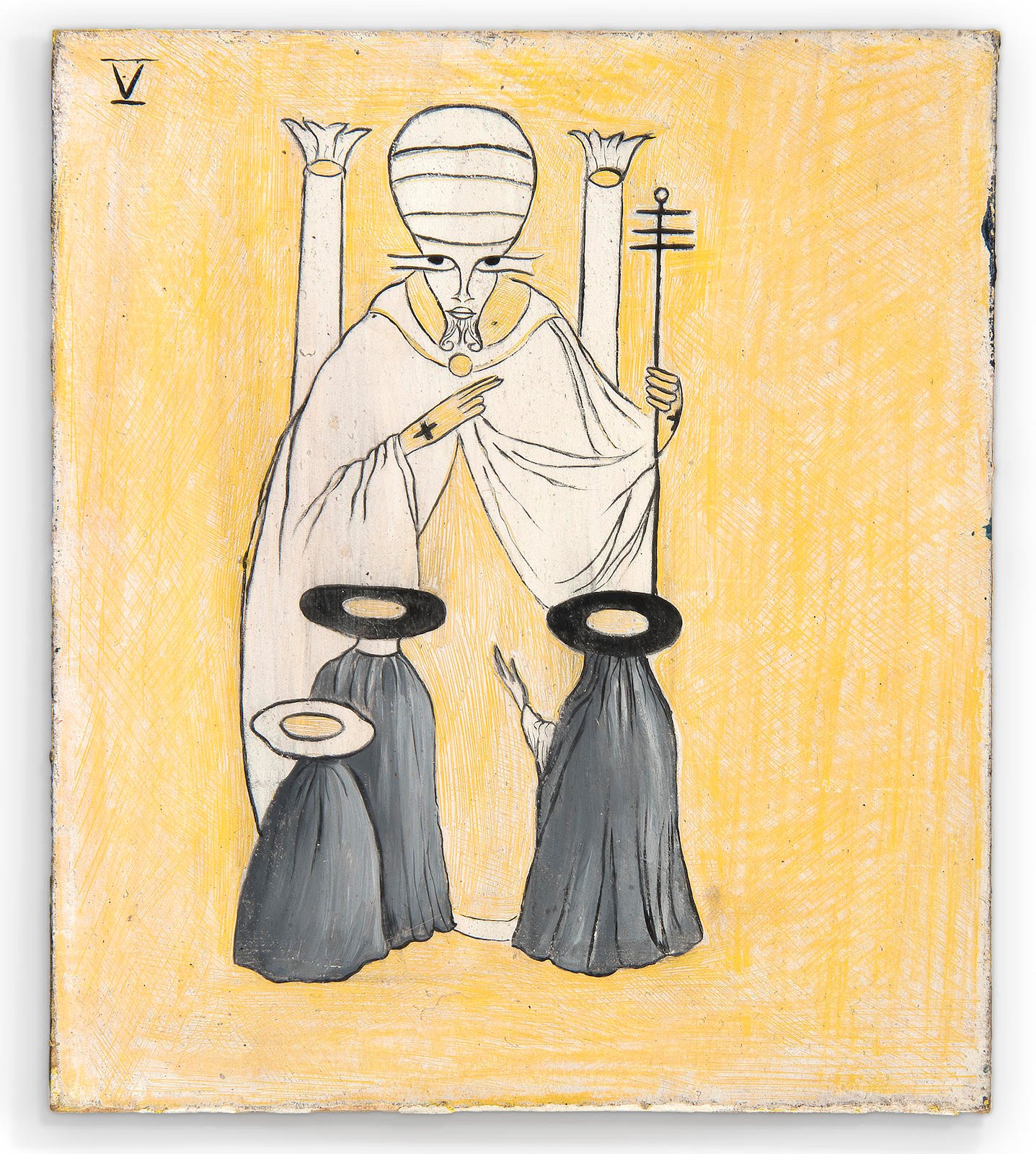

She knew that Carrington, the English-born painter who lived in Mexico and was part of the Surrealist group, was interested in all things occult. She knew she had done paintings based on imagery from tarot cards. But she did not know that Carrington had done a whole suite of small paintings based on the Major Arcana, the 22 trump cards in the standard 78-card pack.

“I was speechless,” Arcq said in a phone conversation. “It was an epiphany.”

She describes it as the greatest surprise of her research for the show, and one of the greatest achievements of the exhibition overall.

These paintings are now the subject of a new book, The Tarot of Leonora Carrington, published by Fulgur Press. A limited edition including the deck in facsimile with an essay on tarot by expert Rachel Pollack, an introduction by the artist’s son, Gabriel Weisz Carrington, and essays by Arcq and art historian Susan Aberth, priced up to $400, sold out within days. A limited edition of the deck alone also went quickly (but will be reissued and available from Fulgur Press direct in January or February). A trade edition of the book will be available in February, priced at $50.

Carrington took the Surrealist world by storm when, at just 19 years old, she fled the confinement of a wealthy English family for the freewheeling scene in Paris. André Breton took up her cause, and her work went on view in the Surrealist group’s exhibitions and publications. She left Europe for Mexico during the Second World War, where she befriended cultural figures including the filmmaker Luis Buñuel. Now firmly part of the art-historical canon, Carrington saw her work exhibited in museums worldwide before she died in 2011 at age 94. Interest has only grown since.

The Tarot of Leonora Carrington, published by Fulgur Press.

For Aberth, the discovery of the deck sheds new light on Carrington’s body of work.

“Once we saw the tarot, we immediately knew that this was very important to the iconography,” she said in a phone interview. “For many years, people thought her work was playful, a bit like fairy tales. But it’s a very serious study of esoteric principles—primary among them the tarot.” She describes a famous 1938 portrait of her then-lover, the artist Max Ernst, as being “exactly like” the Hermit from the tarot deck.

Many versions of the tarot deck exist, but, by Arcq’s lights, Carrington’s is unique. She primarily drew inspiration from the well-known Rider-Waite set, as well as the Marseilles tarot. But her use of gold and silver leaf, mostly when the imagery shows the sun or the moon, reaches back to conventions of older sets, and her inspirations were diverse: the figure of the High Priestess, Arcq says, looks to Egyptian renditions of the goddess Isis.

The new book scratches several itches, including an overdue interest in women artists who were overshadowed by their male peers, and a new enthusiasm for artists with a taste for the occult (such as Hilma af Klint and Agnes Pelton).

But while the occult may be hot right now, Aberth points out that for Carrington, it wasn’t just a means of fortune-telling, but rather a guiding principle on a much higher plane.

“For a certain portion of the population, one of tarot’s appeals is divination,” she says. “Like in all divination practices, there is the element of chance unfolding a higher truth. But Carrington was way beyond divination. She studied tarot very seriously as a means to journey upon a higher realization path. It has a psychological as well as a spiritual element. It’s a guide for greater self-knowledge.”