When Lisa Spellman opened 303 Gallery in 1984, the name was both a literal reference to the location—the address of the building was 303 Park Avenue South—and an allusion to the model that inspired it: Alfred Stieglitz’s secret Intimate Gallery, located in Room 303 of its own building, which was dedicated to offering memorable encounters with forward-thinking artists.

“I never thought I’d move,” Spellman told artnet News, referring to the practicality of the gallery’s name. She was speaking in a back room of 303’s current location, a shiny two-story, 12,000-square-foot space opened in 2016. “Honestly, I really never thought the gallery was going to work. I was ambitious, but I didn’t think that far ahead.”

How could she? Spellman was still in college when she founded 303; she slept in the back of the exhibition space. At that time, during the clubby, high-flying East Village boom, galleries like hers opened and closed every day. That she could last a year was a lofty proposition.

But here we are. This week, Spellman is celebrating her gallery’s 35th anniversary with the launch of both a book and a group show of the same name: “303 Gallery: 35 Years.”

The art world has changed a great deal during this time, enduring the increasing dominance of the “mega gallery,” global fair fever, the rise of e-commerce. Through it all, 303 has remained one of New York’s consistently great galleries—one that has maintained a downtown, slightly anti-authority vibe even as it inhabits a sleek, developer-built high rise.

Over the years, 303 has launched (or solidified) the careers of numerous contemporary art stars, many of whom are still on Spellman’s roster today, including Doug Aitken, Karen Kilimnik, and Alicja Kwade. And many other art-world titans have passed through. Richard Prince, once married to Spellman, showed at the gallery, as did Jeff Koons. Christopher Wool first displayed Apocalypse Now at 303 in 1988. Rirkrit Tiravanija’s landmark Untitled (Free) exhibition, where he served rice and Thai curry to gallerygoers, took place there in 1992. Collier Schorr started as the gallery’s first intern; Gavin Brown worked there in the ‘90s.

Ahead of the anniversary celebrations, Spellman sat down with artnet News to take stock of her gallery and look back at how she got here.

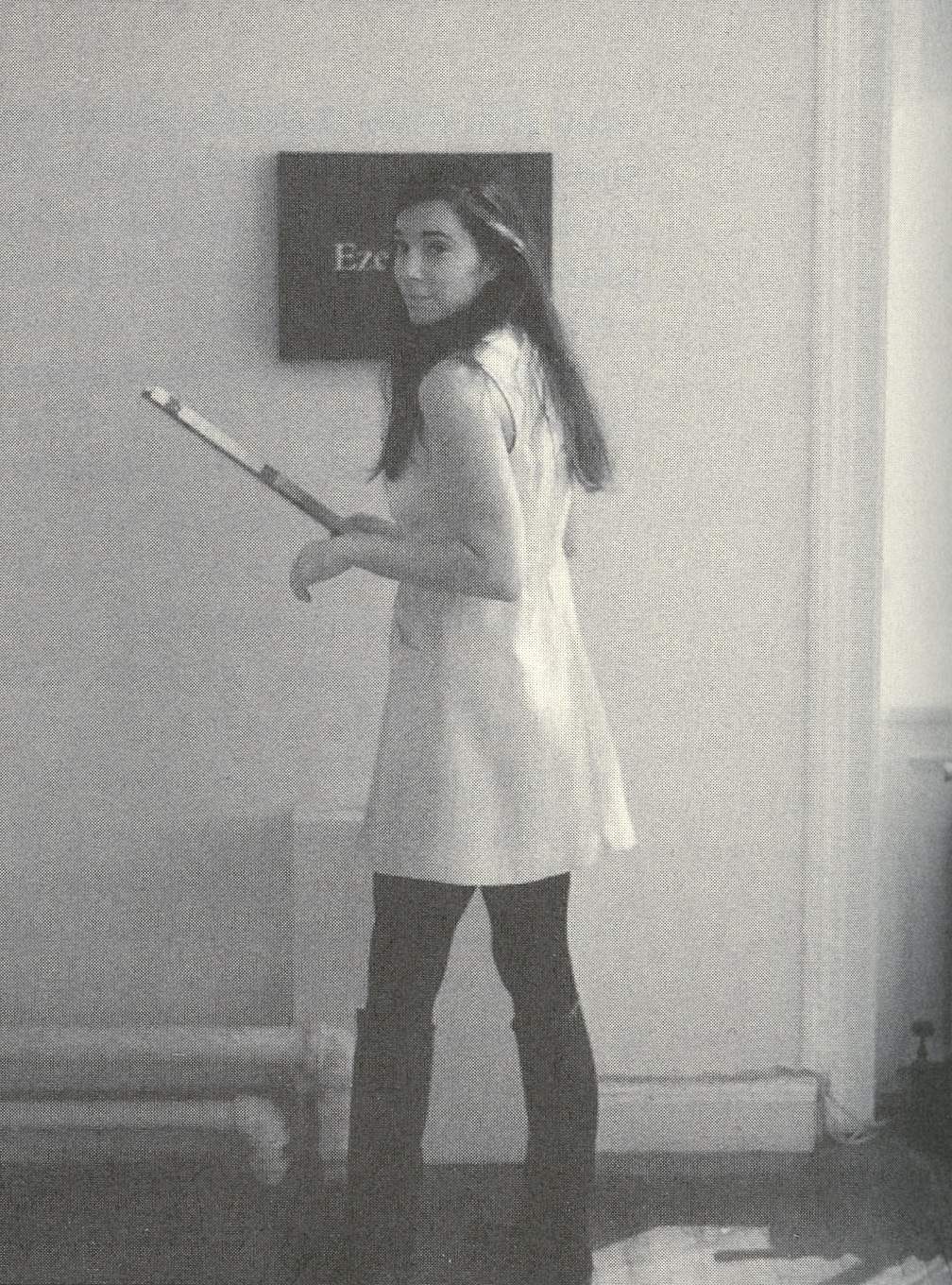

Lisa Spellman, 2011. Photo: Caroline Claisse. Courtesy of 303 Gallery.

Thirty years ago, you opened the gallery in a live-work space that cost less than $500 per month. You were still in college. Do you ever just look back in awe at how far you’ve come—and the art world has changed—since then?

Sometimes. It took a long time, but I like growing slowly; I think it’s more sustainable for everyone. I wouldn’t say slow and steady wins the race, necessarily, but slow and steady seems like a good strategy in the art world because things are so implosive.

Despite sustained success for decades now, you’ve resisted the urge to strive for “mega-gallery” status like some of your peers. Why is that?

I had two spaces for a while—we were on 22nd Street for 15 years when I bought the building on 21st Street. I’m not ruling out the idea of doing something similar in the future. I’m always thinking in the back of my mind, how I can grow the gallery? What’s a good next step? For the last five years, I was very focused on tearing down the old gallery, then building this one. We had to do it all from scratch. Now, I’m always thinking in the back of my head where another space would be, what city it might be in. I didn’t really love having two spaces in New York because it tends to divide the staff, and we really need to be together.

I want to be able to live my life and also go to shows. I never wanted to go to a 303 meeting every ten days. I’d rather be available to the artists—to go to museum openings and support their off-site projects. Sure, I can see a second space. But eight or nine? No. I’m 60 now. I’m just not that type of person.

Installation view, “303 Gallery: 35 Years,” 303 Gallery, 2019. Photo: John Berens. Courtesy of 303 Gallery, New York.

You’ve made a big investment in Chelsea. Presumably, you’re not leaving the space anytime soon.

No, but obviously the neighborhood is going through intensive transitions.

We’re seeing a number of galleries decamp to other neighborhoods—Tribeca, Harlem, the Upper East Side. Does that make you worried about having just doubled down on Chelsea?

No. I’ve been here since ’95, and I’ve moved around a lot. I’m incredibly happy with the space that we built. I mean, I know there’s a lot of stink on Chelsea, but as long as people are still coming to see the shows, that’s all that matters.

Colin de Land and Lisa Spellman on East 6th Street. Courtesy of 303 Gallery, New York.

You have a reputation of forming close personal relationships with many of your artists. Can you speak to the importance of that?

It’s critical. The gallery is only as strong as its artists. It’s not that easy. It’s not like you wake up every day and think of new artists that you want to show. It’s hard to find artists that really make sense for the program and it’s even harder to get those artists to agree to join you. Those relationships are precious, so when you have them you just don’t want to let them go. Obviously, you came together for a reason, so if that can continue to be a productive and fruitful relationship, it seems worth the investment.

Has the process of bringing on new artists gotten easier throughout the years?

No, harder. Some artists don’t want galleries. They say, “Hey, I can just represent myself and just do what I want.”

Installation view, “A Project: Robert Gober Christopher Wool,” 303 Gallery, 1988. Courtesy of 303 Gallery, New York.

There’s been a lot of speculation about that particular idea, that we might be transitioning into a time when artists rely less on galleries to promote and sell their work. We’ve seen it in other industries—some musicians, for instance, are eschewing major labels in favor of self-producing and self-distributing their work. There are artists doing a similar thing now, albeit on a much lower level and it hasn’t really impacted the gallery system yet. Do you foresee that changing?

Not really. I think artists really rely on galleries. The cost for a musician is probably much lower than that of an artist who needs, say, a sculpture fabricated or a film produced. They need help managing shipping costs with museums and paying for publications, and then there’s the critical back-and-forth about the work itself. I think it’s only a conversation for older, established artists. Some veteran artists will definitely get to a point where they’re like, “Listen, I’ve got my own studio, I’ve got ten assistants. I just want to represent myself and I’ll deal with it when I show.” They don’t want to be tied down to anybody, which I totally understand.

A number of high-profile artists who built the foundations of their early careers through your gallery have, throughout the years, departed to other dealers.

Yeah, that’s really painful. It just happens in a flash. Then you just have to deal and move on, you know? It hurts but what can you do? It’s just the name of the game. Sometimes, after some time has passed—maybe six months or a year down the road—I can see it from their perspective. And maybe I agree with their decision then, and maybe I don’t. I have the luxury of time to see if I can learn a lesson from it. You take it personally, but then you try to learn. What was absent? What can I bring to the table in the future? Or maybe that person didn’t really go on to do a whole lot after leaving us. So that’s kind of interesting too.

Lisa Spellman in the 303 Gallery back office. Courtesy of 303 Gallery, New York.

Do you maintain good relationships with those artists after the fact?

No, but it’s not through me shutting the door. If we’re not working together, it just hard. We’re all busy. It’s just like a breakup. I don’t have any hard feelings. Two artists—Larry Johnson and Sue Williams—have come back.

You launched the gallery’s publishing arm, 303inPrint, four years ago. A number of galleries have started to dip their toes in the editorial waters. What was the impetus for you?

I think it just came from going to the Printed Matter Book Fair for years. I’ve always loved catalogs and zines—everything about them. In the beginning, I wanted to do small publications with the artists and see how it would go. It’s also important to keep artists engaged. I’m sure some of them get a little bored after, say, their third show. A book is a nice little extra thing that they can get involved in. And so many artists are really into artists’ books.

Cover of “303 Gallery: 35 Years,” published 2019 by 303inPrint, designed by Common Name, New York. Courtesy of 303 Gallery, New York.

From your perspective, how has the landscape of collectors evolved over 35 years?

There were maybe 50 collectors when I opened the gallery. The stakes seemed higher then. Everything is so global now; everyone’s richer. The risk is diluted in a way, spread out. I love dealing with collectors themselves. But the role of the art advisor has grown to a whole other level. There are a lot more advisors now than there were 35 years ago.

How do you feel about that?

I really appreciate the work that they do, because it’s time consuming to educate collectors and show them work from all over the world. When they bring in a prepared client, it makes the experience that much more enjoyable. Whereas back in the old days, you would practically have to hold seminars on what appropriation and institutional critique were. Still, I love New York City collectors because I feel most of them are still old school. They come to the gallery themselves. They look at the work.

It’s changed a lot though. When I started the gallery, entertainment didn’t really exist like it does today. There was the opening, then there was the closing. Everything was more artist-based then. You would go to people’s houses. Now it’s almost like galleries need to open up an entertainment division. [Laughs]

Collier Schorr, What! Are you Jealous? (1996-2013). Courtesy of 303 Gallery, New York.

What have you learned about gallery openings? How do you throw a good one?

That’s seriously a format that needs to be reimagined. I really don’t know what the answer is. I mean, when I first opened, it was more of a club vibe. You had to get a bouncer for the door. We would serve crazy amounts of liquor, the event would be four hours long, then you did an afterparty at the club. Everybody was out until 4 a.m. I think openings should have music. Why do openings not have music?

What about art-world influencers—these people who go to openings and fairs to take their picture in front of an artwork? How do you feel about that?

It’s weird, but if it brings people into the gallery, that’s fine. We had really weird, freaky things happen in the gallery way before Instagram. We had a nudist. He would call ahead and say he was coming. Then he would go to a corner of the gallery and undress.

Rodney Graham, Halcion Sleep (1994).© Rodney Graham. Courtesy of 303 Gallery, New York.

What’s the weirdest thing that’s happened in the gallery?

Oh god, there’s so much. You have no idea the weird stuff that goes on at galleries. I once found somebody living in a video installation. [Laughs] Well, not living, but they were there for the whole day. When I locked up the gallery at night and went to leave, I saw this person emerge in the dark. For a second it was just me looking at him through the window and him looking back at me—it was so trippy. I had locked him in and was thinking to myself, “Oh god, how do I get him out now?”

There was one time in our SoHo space, when we were on the second floor, that the gallery got broken into. The people who did it had ridden on top of the elevator, then opened the doors to our space with a crowbar. They stole a couple of really hard-ass photographs—one was a picture of the back of a man who had leprosy. I mean, these were not pretty photographs. That was all they took. I think they tried to pull the fax machine from the wall too, but they left it behind. Then, our in-house photographer at the time—the person who documented all of our shows—found the photographs for sale on a blanket near Cooper Union a few days later. So he bought each one back for like $50. At least that was a happy ending. [Laughs] It’s just insane, the weirdness that goes on in galleries. It’s actually getting less weird now.

What’s one strange talent that an artist on your roster has that we wouldn’t know about?

Hmmmm…I don’t know. Rodney Graham is an amazing musician, but I guess that’s not weird. Doug Aitken is an amazing surfer, but that’s probably not a secret. Our first archivist was a balloon artist. Sue Williams used to love him. All of the artists who had kids did. He would be the archivist by day and then a balloon-maker at night, going to all their kids’ birthday parties.

Doug Aitken, Inflection (1992). Courtesy of 303 Gallery, New York.

Who’s the funniest?

Well, Doug is really hilarious, and he’s an incredible storyteller. Sue Williams is accidentally funny. Karen Kilimnik is so funny—she just comes up with the best lines. I don’t know if people really know that she’s also a big anti-GMO activist. She only will drink non-homogenized milk and will go to great lengths to find dairy products that aren’t homogenized. Everything has to be raw.

Who’s the quirkiest or the most fastidious? Anyone that will, say, only eat the green M&Ms?

Hans-Peter Feldmann does not like to talk when he eats. He’s very old school.

“303 Gallery: 35 Years” will be on view at 303 Gallery through August 16, 2019.