In David Cronenberg’s 1979 film The Brood a controversial psychotherapist accidentally calls forth a litter of killer children from the body of a disturbed patient by uncorking her repressed demons. In Lisa Yuskavage’s identically titled Rose Art Museum survey, the artist arrays some of the more grotesque, gorgeously painted creatures she has spawned over the last quarter century. The show is a trailer that offers career highlights, but it makes an unflaggingly forceful point. Few pictures painted by anyone anywhere today produce the mental havoc engendered by Yuskavage’s exquisitely wanton creatures.

Yuskavage is a commanding presence among contemporary artists. As a painter, she reinvented the modern figure (mostly female, in her case) together with a handful of other 1990s brush-and-canvas radicals (including Neo Rauch, Chris Ofili, and John Currin). As a conceptualist, she out-transgressed most art polemicists and feminists, both of her and subsequent generations. Rough mischief served up with masterful skill has, over time, become the artist’s painterly signature—an achievement akin to doing dirty stand-up comedy in rhyming couplets. And like a filthy joke that gets beautified (The Aristocrats comes to mind), Yuskavage’s penchant for combining bravado with impishness has influenced other artists.

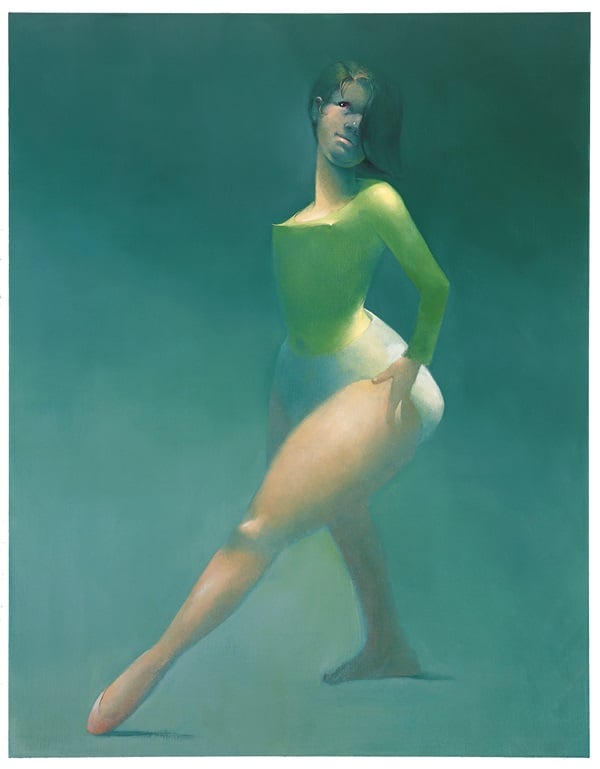

Lisa Yuskavage, The Ones That Don’t Want To: Buttons (1991). Private Collection, London.

Image: Courtesy the artist and David Zwirner, New York/London

Looking back, it’s clear that Yuskavage pioneered once barren artistic territory now claimed by loads of artists. Among the non-painters are figures like Jordan Wolfson, whose creepy yet alluring animatronic stripper sculpture could have easily been inspired by one of Yuskavage’s bodacious freaks.

Within her own medium, the Philadelphia-born, Yale-educated artist’s influence appears both general and specific—like the color of the sky or the average woman’s self-image. On the one hand, it’s unthinkable to conceive of today’s well-behaved expressionistic pictures—like, say, those of painter Dana Schutz—without Yuskavage’s trailblazing example. On the other, the veteran artist’s Trojan Horse aesthetic, which subtly conveys low content via painterly sophistication, renders similarly stylized figuration Yuskavage-lite.

Lisa Yuskavage, Brood (2005-2006). From the collection of Jeffrey A. Altman.

Image: Courtesy the artist and David Zwirner, New York/London

In the words of Pablo Picasso, “someone does it first, then someone does it pretty.” The historical irony is that Yuskavage is also uniquely responsible for bringing painting technique back into vogue, as is evident from the dazzlingly disturbing canvases of scantily clad women and a few men on view at the Rose.

Less a retrospective than a survey of multi-panel works the artist has made during the last 25 years—she terms them “diptychs, triptychs and poliptychs”—the show’s 27 paintings represent a career spent poring over the exalted history of European art and, also, our modern obsession with body image.

The result is a bawdy brood of shocking figures painted with classical luminosity. Despite Yuskavage’s formal delicacy and love of bright colors, it’s no stretch to say that the best of her works are as dark as Francisco Goya’s Black Paintings.

Lisa Yuskavage, Piggyback (2006). Private Collection.

Image: Courtesy the artist and David Zwirner, New York/London

Deftly curated by Rose Museum Director Christopher Bedford, the show begins with four breakthrough canvases that saw the artist crack open the code on a key discovery: the idea that negative attributes and feelings can be literally embodied in luscious color. Titled The Ones That Don’t Want To: Black Baby (1991-1992), Bad Baby (1991), Buttons (1991), and Kelly Marie (1992), these panels each depict a central female figure that is both pantless and nearly dissolved in a warm wash of color.

The paintings elicit feelings of trauma, shame and embarrassment in the viewer—because color is connected via a neural superhighway to the brain’s emotional center—in glowing versions of red, green, purple, and blue. Gertrude Stein once described her mastery of the world this way: “It is all so confusing, but I am not at all confused.” Yuskavage’s girls—less blustery, more forthright and fully phantasmagoric—are confused in Technicolor.

Lisa Yuskavage, Wilderness (2009). Collection of Liz and Eric Lefkofsky.

Image: Courtesy the artist and David Zwirner, New York/London

Directly in front of these paintings, which Yuskavage has christened her “Bad Babies,” is the artist’s most recent contribution to her oeuvre, Hippies (2013). One of the exhibition’s five single-panel canvases, the picture depicts a shadowy landscape inhabited by a central female Venus; the heads, torsos, and legs of four male flower children pop up behind her like the arms of an Indian deity. Though less overtly sexualized and strident than Yuskavage’s earlier work, this painting is still about color as a way of creating character, mood, and, ultimately, narrative in a painting. An alternate title for the work might be “Savages.” A riot of anti-utopianism is also embedded in this portrait of the Roman goddess of love and her slinky, androgynous ids.

Yuskavage’s first US museum solo in more than 15 years, “The Brood” sketches in some of the many high points of this artist’s career, while reminding the viewer of the oversized envelopes she has consistently pushed—often to the bafflement of old school-formalists and gender feminists. “Sympathy for the Devil” playing in the elevator this show is not. One more in a string of disruptions of right thinking and good taste, “The Brood” is likely to draw its share of detractors, along with Yuskavage’s growing legion of admirers. The New York painter’s polarizing nature is legendary; the Rose might therefore consider posting a warning sign to offset any potential snit: “Please note that this artist’s paintings are intended to delight, but they are also calculated to offend.”

Lisa Yuskavage, Blonde, Brunette, Redhead (1995). Collection of Yvonne & Leo Villareal.

Image: Courtesy the artist and David Zwirner, New York/London.

Among the many litmus tests included in this must-see show is Yuskavage’s 1995 painting Rorschach Blot. The image, which is bathed in a golden yellow light reminiscent of certain Klimt portraits, depicts a solitary female figure squatting with all holes exposed, her mouth open in a combination of sex-doll availability and Munch-like scream. It is an image that attracts and repels by turns, while viscerally invoking a Jansen’s art history of gallows humor—from Bosch and Breughel to Giacometti and Bacon. In its spectacularly radiant way, Rorschach Blot is a thing of beauty that peals like an emergency vehicle. Some may swoon in response and others may wag their finger—but the painting’s intensity will leave no one indifferent.