Whether or not the little prince ultimately moved to his star we cannot know. What we do know now, however, is where he originally came from. This child who wears the long scarf that floats in the sky, is, in fact, a New Yorker. The French aviator-author Antoine de Saint-Exupéry created his bestselling character in New York City, between 1941 and 1943, while recovering from a plane crash.

This is revealed at The Little Prince: A New York Story, a major exhibition at the Morgan Library & Museum celebrating the 70th anniversary of the book. On view are 43 original watercolors and drawings, as well as the only surviving handwritten draft of The Little Prince, which the Morgan acquired in 1968.

The drawings and manuscript evolved considerably while the author attempted to comprehend the enormity of the events of World War II within the context of a child’s fairytale, so the visitor is offered a rare glimpse into Saint-Exupéry’s creative process. The author made mention of Manhattan and even Rockefeller Center in early drafts; later those were deleted.

Saint-Exupéry also excised numerous characters the little prince meets on Earth, such as an inventor of “pushbuttons that satisfy human desires” and a shopkeeper who gives him a book replete with “slogans that are easy to remember.”

Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, drawing for The Little Prince. The Morgan Library & Museum, New York

© Estate of Antoine de Saint-Exupéry. Photo: Graham S. Haber, 2013.

The exact wording of the famous sentence spoken by the talking fox, “What is essential is invisible to the eye” (“L’essential est invisible pour les yeux”) was so important to Saint-Exupéry that he wrote 15 variations before deciding on the final one.

Familiar scenes from the book make their first appearance in the manuscript, such as when the pilot-narrator first meets the little prince. Other drawings, later excluded, show the pilot asleep on the sand after his plane crashes, and another of him working on the engine. In the end, Saint-Exupéry eliminated all drawings of the wreckage. The story’s narrator says, “I won’t draw my airplane . . . [T]hat would be much too complicated for me.”

Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, drawing for The Little Prince. The Morgan Library & Museum, New York

© Estate of Antoine de Saint-Exupéry. Photo: Graham S. Haber, 2013.

The exhibition includes a remarkable artifact—the actual silver I.D. bracelet Saint-Exupéry was wearing when his own plane went down. This was sometime after July 31, 1944, after he took off from Corsica on a lone reconnaissance mission, just weeks before the liberation of Paris. The bracelet, snagged in a fisherman’s net near Marseille in 1998, is on view for the very first time in the United States. It is inscribed with Saint-Exupéry’s name and his wife’s, and, poignantly, with the name and address of the American publisher of The Little Prince, Reynal & Hitchcock.

The Morgan Library does not include a complete manuscript. The exhibition text explains that the 140-page manuscript is the only surviving handwritten draft of The Little Prince, “aside from two pages that were sold at auction in 2012.”

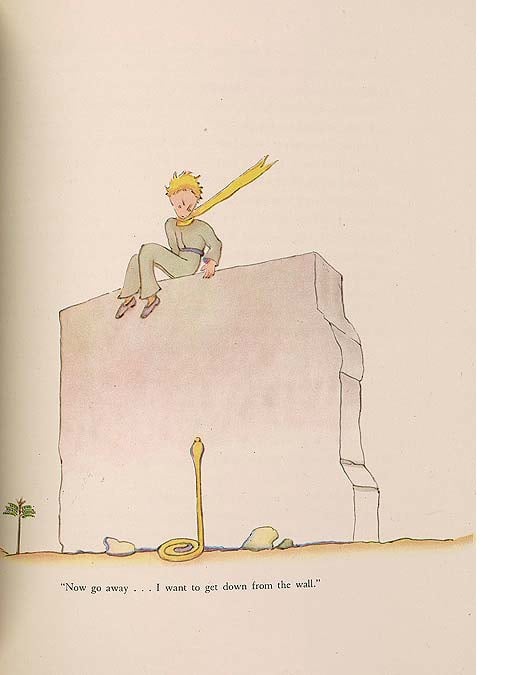

Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, illustration from The Little Prince (New York: Reynal & Hitchcock, 1943).

The Morgan Library & Museum, New York. Photo: Graham S. Haber, 2013.

Reportedly these were discovered in a packet of Saint-Exupéry’s letters that were sent to a French auction house, Art Curiel. The auctioneer’s book and manuscript expert, Benoit Puttermans, was shocked to find that the two barely legible handwritten pages were unpublished versions of chapters 17 and 19. The second page introduces an original character the little prince visits on Earth, a crossword enthusiast who has no time to speak because he is looking for “a six-letter word that starts with G that means ‘gargling.’” (The answer: Guerre).

Art Curiel estimated the pages would sell for €40,000–50,000 ($52,000–65,000). But after eight bidders competed, the two leaves fetched a whopping €311,200 ($400,000), including the buyer’s premium. The winner was a French collector, which seems fitting. Dommage, for the Morgan. These were the two that got away.

“The Little Prince: A New York Story” is on view at the Morgan Library & Museum, 225 Madison Avenue, New York, January 24–April 27, 2014.