For the last three years, Jonathan Anderson, the creative director of the crafts-oriented Spanish fashion label Loewe, has transformed the brand’s Miami Design District store into a makeshift museum every December to greet the hordes descending on Art Basel Miami Beach. A Brit who also oversees his own semi-eponymous label, JW Anderson, the designer has been using the fair as an excuse to curate a recurring exhibition to spotlight the artists he admires, allowing their work to interact with each other, with the space, and with his clothes. More importantly, the shows—each entitled “Chance Encounters,” with this one being “Chance Encounters III”—enable the ideas of art and commerce to interact with one another.

Sometimes Anderson becomes drawn to his artists in a thunderclap; other times it’s a slow burn. He came across the work of ceramicist Sara Flynn around 10 years ago and became transfixed with her fluid, sensual objects. “I’m quite obsessive,” Anderson says of his fascination with ceramics as a medium, which he also highlighted in last year’s exhibition. He likes the fact that ceramics, like fashion, walk the line between utility and decorative.

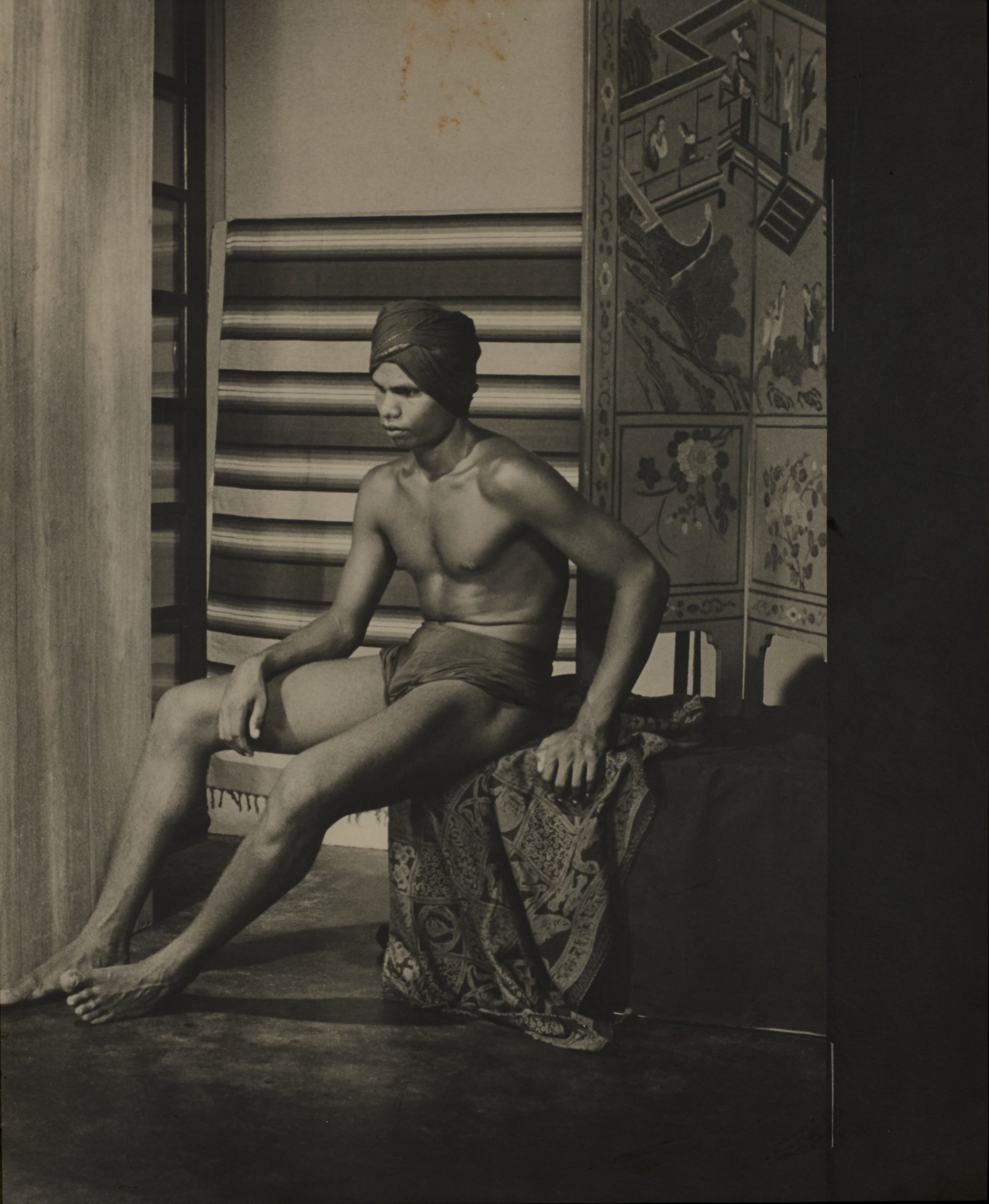

For this show, Anderson commissioned Flynn to create a collection of pieces, which he then juxtaposed the work of two other artists: the Sri Lankan photographer Lionel Wendt, whose homoerotic portraits grace the walls, and Richard Smith, whose imposing sculpture towers above its peers. All will be arrayed within the store’s clinical white interior, in the middle of which Anderson placed a stone granary from the 18th century.

Sarah Flynn’s Faceted Esker Vessel Group (2017). Photo courtesy of Loewe.

“It’s quite random, my process,” Anderson says about his approach to curating, admitting that his fashion design work follows a similar trajectory, taking bits of cultural ephemera and combing or juxtaposing them. Yet, it’s in that very randomness that Anderson says he finds the challenging discoveries that can make his work exciting, unexpected, and—most vitally—unique.

“It was a pinch-me project,” Flynn says of their collaboration, noting that Anderson gave her a lot of leeway in his brief. “He said, ‘I want you to be proud, and I want it to be a body of work that marks your body of work, your skill, and your ability at the moment.’” For Flynn, that meant she could create a collection of objects and know that an audience would not only see them individually but in relation to each other as well—an exciting proposition for her. It’s not often that commissioned work comes with such freedom. “It was like he was saying ‘No, I’m not going to tell you what I like, I want you to present what you think is strongest,’” she says.

Flynn also mentions her work’s relationship with function, a criterion for creation she let go of around a decade ago. “It was a boundary that was holding me back,” she says. “I didn’t want to worry if it was a jug that wouldn’t pour or a vase that would topple over.” That freed her to focus on reacting to and communicating with her material, and the results are seen in the earthy textures and bodily contours of her objects.

Richard Smith’s Shuttle (1975). Photo by Antonio Parente for Flowers Gallery, London and New York.

Placed together, the three artists’ work will no doubt take on new dimensions, an especially exciting proposal considering that both Wendt and Smith have passed away. Their interaction’s with Flynn’s work, will, in a way, reframe them and help them be seen anew—part of Anderson’s thinking behind this project, and a reason why he wanted to present work from multiple artists. “He’s got the vision, I think he could see it before it was even made,” Flynn noted. And while she may be crucial to the end result, she realizes that she’s merely a piece of the puzzle. “I can’t wait to see it put together,” she says.

The culmination won’t be seen until the show is unveiled in December, and then it will run through the holidays and into the new year, serving as a centerpiece for the site where Loewe’s fall collection, which traded in a mumsy, kooky glamor, will hang. Like so much of life in 2017, the exhibit—with its variety of emotions, its mediumistic range, its whiff of forbidden sexuality—appears to highlight the extremes of modern life, the aleatory quality of existence in the digital age.

Add that melding of art and commerce to this mix. Does Anderson think this mix of high and low, sacred and profane, is odd in any way? “Oh no, everything’s all mixed together now anyways,” he says. Fine art and fashion? It’s hard to tell the difference.