With about three dozen participants, Madrid’s annual gallery weekend—an initiative dubbed Apertura (“Opening”)—is quite a bit smaller than its clear role model, the ever-building Berlin Gallery Weekend. Despite Madrid’s world-beating museums, the persistence of ARCO as the world’s best-attended fair, and the presence of a handful of art-circuit staples like Galería Helga de Alvear, its art scene remains relatively modest in scale.

It’s a bit of a cliché, but I’ll still say that this is part of the charm. Apertura’s offerings are not free of some of the played-out tropes of contemporary art—plenty of gimmicky abstraction and undercooked conceptualism—and it has its share of safe bets, from a fine mini-retrospective by the Uruguayan painter Joaquín Torres García at Guillermo de Osma to a polished show of freaky video-sculptures by Tony Oursler at Moisés Pérez de Albéniz. Still, it all feels like a scene with its own close-knit rhythms, and things to discover.

Here are five of those things from Apertura 2016:

Gerardo Rueda, Verdor (1995). Image courtesy Juana de Aizpuru.

“Museo de Arte Abstracto Español” at Juana de Aizpuru

At this venerable gallery, an irresistible bit of art lore: The show celebrates the 50-year anniversary of the founding of the Museo de Arte Abstracto Español in the small town of Cuenca (a couple of hours outside of Madrid), an institution which Alfred Barr, the pioneering MoMA director, once called “the most beautiful museum in the world.” Founded by collector, painter, and all-around mover-and-shaker Fernando Zóbel (1924-1984), it was an outpost for abstraction during a time when Spain was sweltering under a conservative dictatorship.

Aizpuru showcases a selection of works by the so-called “Grupo de Cuenca,” painters sustained by the museum’s promotion of experimental art: Gerardo Rueda, Jordi Teixidor, Gustavo Torner, José María Yturralde, and Zóbel himself, with his own brand of scratchy abstraction. The history lesson is nice, but it is actually work from the 1990s by Gerardo Rueda (1926-1996) that catches my eye: clean, geometric compositions assembled in relief from colored blocks of wood, the joints and slices into the surface functioning as line. Earthy and unpretentious but suave.

Detail of Miguel Angel Barba, Sin título (2015). Image: Ben Davis.

Miguel Ángel Barba at Galería Rafael Pérez Hernando

Continuing a theme, here’s another painter who hails from Cuenca, though much younger (b. 1974). Barba represents a long-term investment for this gallery—one of the four local painters that the gallerist founded the gallery on, and the only one still at it. His most recent work shows that it was worth sticking around. Each canvas features rows of symbols set against a spare white background, playing with how their meaning melts away as you layer them. Sometimes the symbols in question are actual letters, overlaid until they become difficult to read; sometimes these are a lexicon of cartoon icons that repeat in a delicate grid, like the Rosetta Stone for a personal symbolic language.

Ixone Sádaba, You never thought I was strong enough to leave. Neither did I. You have no idea how strong I am. I fear nothing. I will no longer fear anything again. Kurdistan, Iraq. 26 March 2016 (2016). Image courtesy Michel Soskine.

Ixone Sádaba at Michel Soskine

The wall-based assemblages here are the latest—and best—work to come out of the Bilbao-born artist’s trips to Iraqi Kurdistan. Sádaba has been three times, long enough to make friends and see the toll taken by the violence rocking the region. The works at Michel Soskine are like accretions of her personal associations, combining melancholic photo portraits of people she has met along the way with images that evoke their world or bits of scavenged fabric overlaid with poetic, enigmatic texts in Arabic calligraphy. The fragmented but focused constructions evoke the sense of a world trying to hold itself together in the face of inexorable centrifugal pressure.

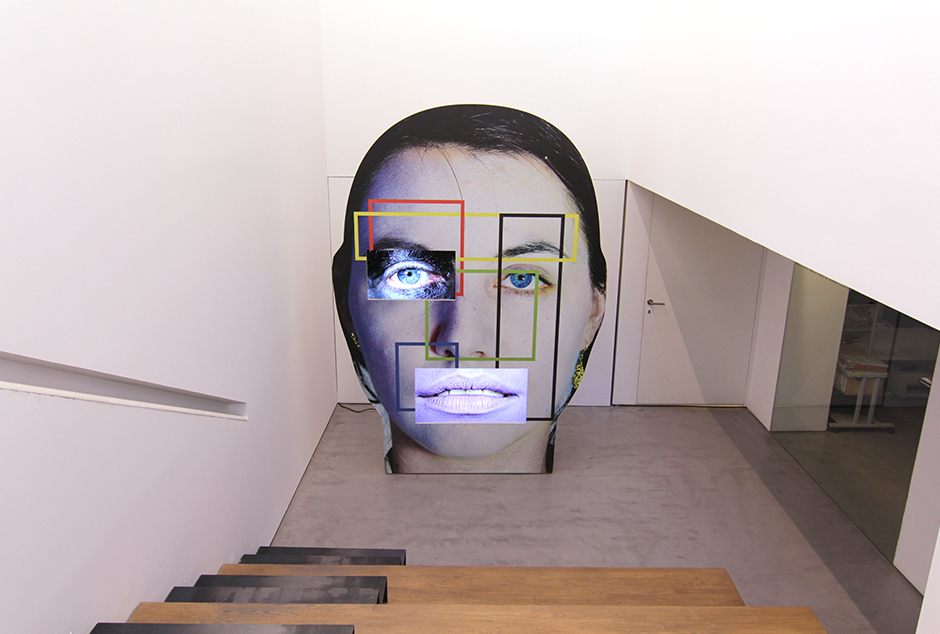

Exhibition view of Daniel Jacoby, ““Sydney would have nothing to hide if others did not have anything to fear” at Maisterravalbuena. Image courtesy Maisterravalbuena.

Daniel Jacoby at Maisterravalbuena

With the elaborate title “Sydney would have nothing to hide if others did not have anything to fear,” this show by the Peruvian artist feels something like taking a late-night trip to a haunted, other-dimensional H&M. Jacoby’s sculptural compositions take their inspiration from cut-rate clothing stores in Lima, offering up assemblage environments patched together from oddball shapes that turn out to be items of clothing stretched out until they achieve a kind of groovy geometric abstraction.

Works by Elena Bajo at García Galería during Apertura. Image: Ben Davis.

Elena Bajo at García Galería

The multi-disciplinary Elena Bajo was born in Madrid but is now based in LA, where she’s the co-founder of an art collective that fights for fossil fuel divestment. That interest is neatly encapsulated with her series of sculptures and reliefs here: simple geometric volumes, their surfaces breaking out with scabby patches that turn out to be masses of crumpled plastic bags. The effect in person is skin-crawlingly tactile (though difficult to capture in words or photos). Plenty of art evokes a scavenged aesthetic; Bajo doesn’t redeem junk, but builds a kind of metaphor for a polluted world eating away at the redemptive promises of art.