With studios and galleries shuttered around the world, artists these days are being forced to find new ways to make and share their work—and many are turning to the US Postal service for help.

Mail art, a form that goes back more than six decades, is enjoying a mini-renaissance, with a number of postal projects popping up in recent weeks as people seek a form of connection not mediated by screens.

Many campaigns—such as the one organized by Nashville-based artist Jason Brown, who is collecting works of art by anyone willing to submit them—are meant to document this unprecedented moment. (The works collected by Brown will be donated to the Vanderbilt University Library.)

Others are more absurdist in nature, channeling the roots of the art form. For instance, Civilization, a print publication made up of conversations overheard in New York, will send you a customized artwork through the mail for $3.

“Mail art is perfect for right now,” says Jason Pickleman, an artist and designer who runs the small Chicago-based gallery Lawrence & Clark. He is currently soliciting envelope-sized works for what will hopefully become an in-person exhibition. “It’s compact. It’s social and also socially distanced from its audience. That makes it exceptionally relevant today.”

Ever since Pickleman issued an open call for mail-based artworks in 2018 (he received 100 submission that year), mail art exhibitions have become annual traditions at the gallery. (In 2019, he got 150 works.) Each year, the gallery’s mailman chooses the “best in show,” and winners get a book of Forever Stamps.

Whether the show will take place this year is still up in the air, as is the future of Lawrence & Clark altogether. The gallery, which doesn’t sell art, but instead is used to display Pickleman’s collection and the work of artists in his community, is supported by his design practice. In the last two months, he’s lost 90 percent of his clients.

“The gallery is an additional expense that we may no longer be able to afford,” he says. “It’s collateral damage.”

Mail art submissions. Courtesy of Jason Pickleman and Lawrence & Clark.

So far, Pickleman has received roughly 100 artworks for this year’s show, and he expects 200 more. If the show can’t take place in person—the gallery’s lease is up this summer—then he will put something together over Instagram and Facebook.

Though the roots of the art form were born in various Modernist and early Postmodernist movements, particularly Dadaism and Fluxus, mail art as we know it has become synonymous with Ray Johnson, who is thought to have pioneered the model in the late 1950s.

Johnson, once dubbed “New York’s most famous unknown artist,” began mailing art to friends that he made from images culled from magazines and other sources, which he called “moticos.” Often, they came with instructions that invited the recipient to add to the artwork, exquisite corpse-style, and send it along to someone else.

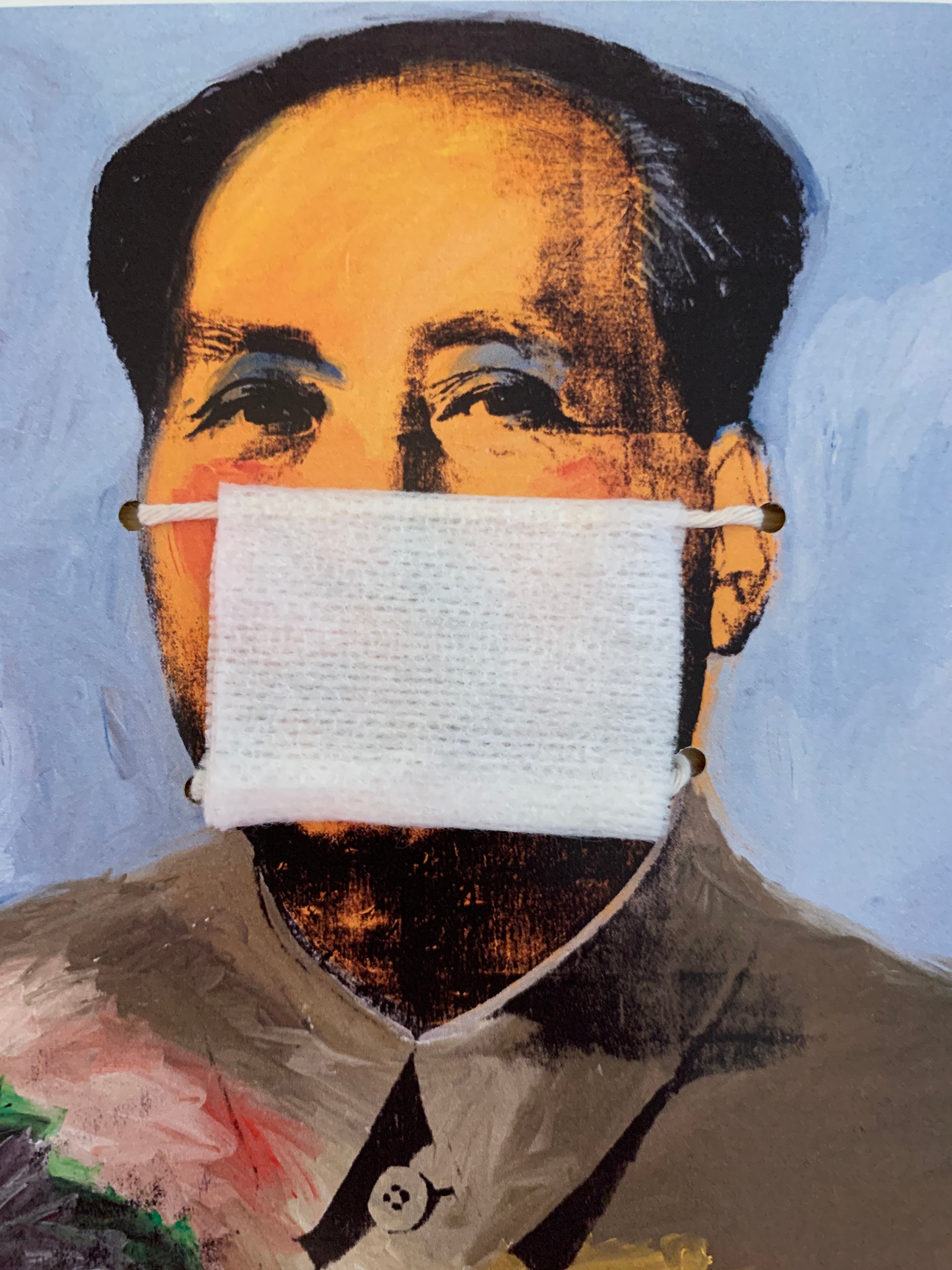

Mail art by Margaret Rizzio. Courtesy of Printed Matter.

The idea was to create a form of artistic production that bypassed the institutionalized channels of the contemporary art world and democratized the process of dissemination.

And even today, the model is democratic, which is a big part of the appeal, says Johanna Rietveld, a manager of the New York-based bookstore Printed Matter.

“Anybody can be a mail artist and become part of that network. Even if you don’t feel like a mail artist, you are a mail artist.”

Through Printed Matter, Rietveld launched an open call for mail art submissions in early April with a simple prompt: “We live in real time.”

“It’s about experiencing the moment, moving through life in real time, while also looking ahead to the moment when we’ll be thinking back on it,” she says, explaining the impetus for the project. “So much changed within a few days. You couldn’t plan ahead. It’s about living a very day-to-day life.”

The store is collecting submissions from all over the world (emails are also accepted), and will compile a selection into a small book when non-essential businesses can resume. (All submissions will live on in Printed Matter’s archives as well.)

So far, Printed Matter has received nearly 400 works of art, from collages and textiles, to stickers, and even an old telephone. And the artists behind them are similarly diverse. Rietveld notes that they’ve received pieces from a 5-year-old child and a 101-year-old woman; from 30 students in a university program, where a professor turned the open call into an assignment; and from at least one inmate in a correctional facility.

“Mail art creates this sense of connectivity in a time when everybody is isolated,” Rietveld says. “It’s connectivity in this analogue, old-school way.”