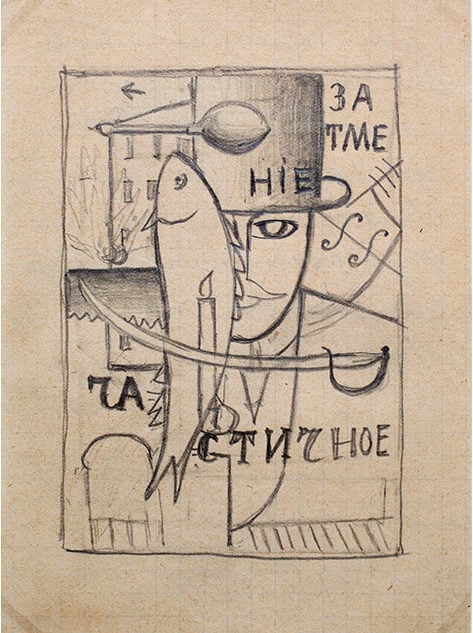

A newly rediscovered drawing by Kazimir Malevich will go on view at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam today, after former head of collections at the museum, Geurt Imanse, discovered the drawing hidden inside a monograph during a recent inventory. Previously unknown, it appears to be a preliminary sketch for the 1914 painting An Englishman in Moscow.

The Stedelijk has the largest collection of Malevich work outside Russia. It also cares for the Khardzhiev Collection, amassed from the late 1920s on by literary scholar Nikolai Khardzhiev, a friend and contemporary to artists like Malevich, El Lissitzky, and Vladimir Tatlin. In 1992, Khardzhiev fled Russia and took his collection to Amsterdam.

“This discovery not only affirms the importance of research, it also demonstrates the powerful synergy between our Malevich collection and the Khardzhiev Collection,” said director Beatrix Ruf in a press release.

Kazimir Malevich, An Englishman in Moscow, (1914). Collection Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam, Photo courtesy Wikimedia Commons.

The 10×14 inch pencil-on-paper drawing, and its resulting painting, are said to be products of Malevich’s “alogical” period. After working through a cubist style around 1912-13, the artist, according to the Tate, “rejected reason” entirely in 1914. He began working in a fragmented style he called “Alogical Fevralism,” exemplified in An Englishman in Moscow’s combination of a half a man’s face wearing a top hat, layered with a fish, spoon, sword, Cyrillic letters, and abstract blocks of color.

One year later in 1915, Malevich painted the first Black Square. Recent research into that painting revealed that he actually painted two compositions on the canvas—deemed Cubo-Futurist and proto-Suprematist—before eclipsing them both in what has become one of the most iconic works in the history of the avant-garde. (Pun intended: when the work was first displayed, at “The Last Futurist Exhibition of Painting 0:10” in Petrograd, it hung in the top corner of the room, like a religious icon would in a Russian Orthodox home.)

For fans of the historical Russian Avant-Garde, today also marks the first part of the bi-annual Khardzhiev symposium, which will bring together a handful of scholars to speak about their latest research into the genre.