There are many ways to look at a photograph by the late Malick Sidibé, and all of them offer different insights into the context of their place and time. Currently on view at Paris’s Fondation Cartier, “Mali Twist” is the largest exhibition of the African photographer’s work to date; it’s a tribute to the man known as “the eye of Bamako,” and a return, one year after his death, to the very institution that gave the Malian artist his first showing outside of Africa in 1995. It is also an attempt at offering a holistic reading of his most iconic work, from the period between 1960-1980.

In his studio portraits and photography of Bamako’s vibrant nightlife, Sidibé captured the rapture and bustle of the years around Mali’s independence from France, in 1960. For his nightlife scenes, Sidibé would hit the clubs every weekend, staying up until the early hours of the morning to develop the photographs taken at the so-called “surprise parties” and the beat and Yé-Yé parties. (Derived from “yeah, yeah,” it was France’s non-English-language answer to rock ‘n’ roll). On Mondays, he would display the prints, grouped together according to the clubs where they had been taken, on the wall outside his studio. Being captured by his lens became a rite of passage: The young men would look for photos of themselves, and buy them as souvenirs, sometimes to give their dates.

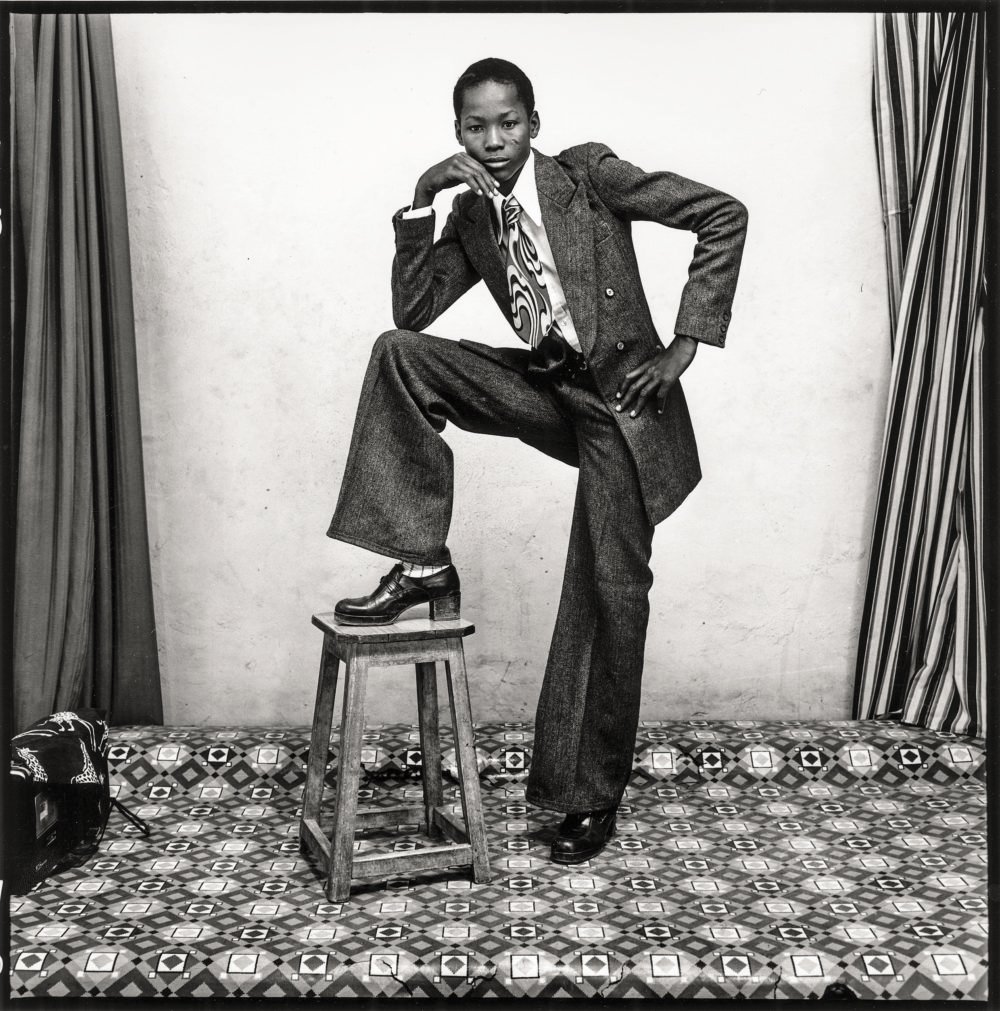

Malick Sidibé’s Regardez-moi ! (1962). Collection Fondation Cartier pour l’art contemporain, Paris, ©Malick Sidibé

The exhibition, curated by André Magnin and Brigitte Ollier, features more than 250 images and archival material, including signature studio photographs that have never been developed before. Alongside his most well-known images such as Nuit de noel (1963)—which Time magazine lists in their 100 Most Influential Images of All Time—is his lesser-known yet striking outdoor photography taken along the banks of the Niger river, which some critics regard as his most skilful. “This is my personal view,” writes African photography historian Vincent Godeau, “but I see Malick more as an outdoor photographer. His studio portraits seem to be nostalgic for the open-air shots.”

By documenting Bamako’s youth culture and its social clubs—with names like The Sputniks or Black Socks, to indicate specific music tastes—and the flamboyant style of the suave rock ‘n’ roll fans, Sidibé is credited with revealing a different image of life in West Africa, which was a contrast to stereotypical images of Africans seen in the West. “For me, photography is all about youth,” he famously told an interviewer. “It’s about a happy world full of joy, not some kid crying on a street corner or a sick person.”

Malick Sidibé’s Dansez le twist, (1965). Collection Fondation Cartier pour l’art contemporain, Paris, ©Malick Sidibé

In 1992, André Magnin, the show’s curator, came across Sidibé’s work by chance on a trip to Mali together with photographers Bernard Descamps and Françoise Huguier, where they had gone, on the behest of French collector Jean Pigozzi, to seek out another photographer, Seydou Keïta. Wielding a photograph taken by the older Keïta, which had been shown anonymously in 1991 at the New Museum’s survey of contemporary African art in New York, Magnin was taken by a taxi driver to Sidibé’s studio instead.

The two photographers, one capturing colonial-era Mali, and the other, the hopefulness of its early days of independence, became the most influential and recognized image makers to have come out of Mali. The exhibition at the Fondation Cartier (until February 25, 2018) points to Sidibé’s influence on a younger generation of artists with contemporary paintings by JP Mika, who creates zippy, colorful portraits that echo Sidibé’s studio shots. The photographer captured his subjects sporting sharp crease of their exaggerated bell bottoms, or showing off prized possessions, such as a shiny motorcycles or livestock.

Malick Sidibé’s Fans de James Brown, (1965). Collection Fondation Cartier pour l’art contemporain, Paris, ©Malick Sidibé

Sidibé won recognition for his work later in life, becoming, in 2003, the first African to receive the Hasselblad Award for photography. In 2007, he became the first African and the first photographer to win the Venice Biennale’s Golden Lion for Lifetime Achievement, within the show “Think with the Senses Feel with the Mind,” curated by Robert Storr.

The works in the survey and the image of Bamako captured here also speak of a bygone era and the political transformations in the world since. As the baby-boomers, who consumed music from the West, dressed to the nines, and danced through the night, grew older, and the country became poorer and more religiously extremist, photographs such as Sidibé’s would be impossible today.

Malick Sidibé’s Combat des amis avec pierres au bord du Niger, (1976). Collection Fondation Cartier pour l’art contemporain, Paris, ©Malick Sidibé

The sense of joy and freedom his photographs so elegantly convey, and the insouciance of post-colonial Bamako, will remain the definitive visual documents of what in hindsight seem like golden years.

Malick Sidibé, “Mali Twist,” is on view at the Fondation Cartier, Paris, until February 25, 2018