Within the art world, it is not uncommon to discover generations of creative minds—whether it’s a family of gallerists, collectors, or artists, creative talents sometimes pass down from one generation to the next.

López-Izquierdo family is a perfect example of this phenomenon, which now boasts its fifth generation of architects and artists. Starting in the 1900s, the López-Izquierdo architects are responsible for forming a large part of Madrid’s cityscape, with several buildings surviving to the present day.

The current generation of architects is taking their family’s talents abroad leading architectural projects in Paris and Rio de Janeiro. What have these younger generations learned from past generations and how does it feel to carry such an incredible legacy into the future?

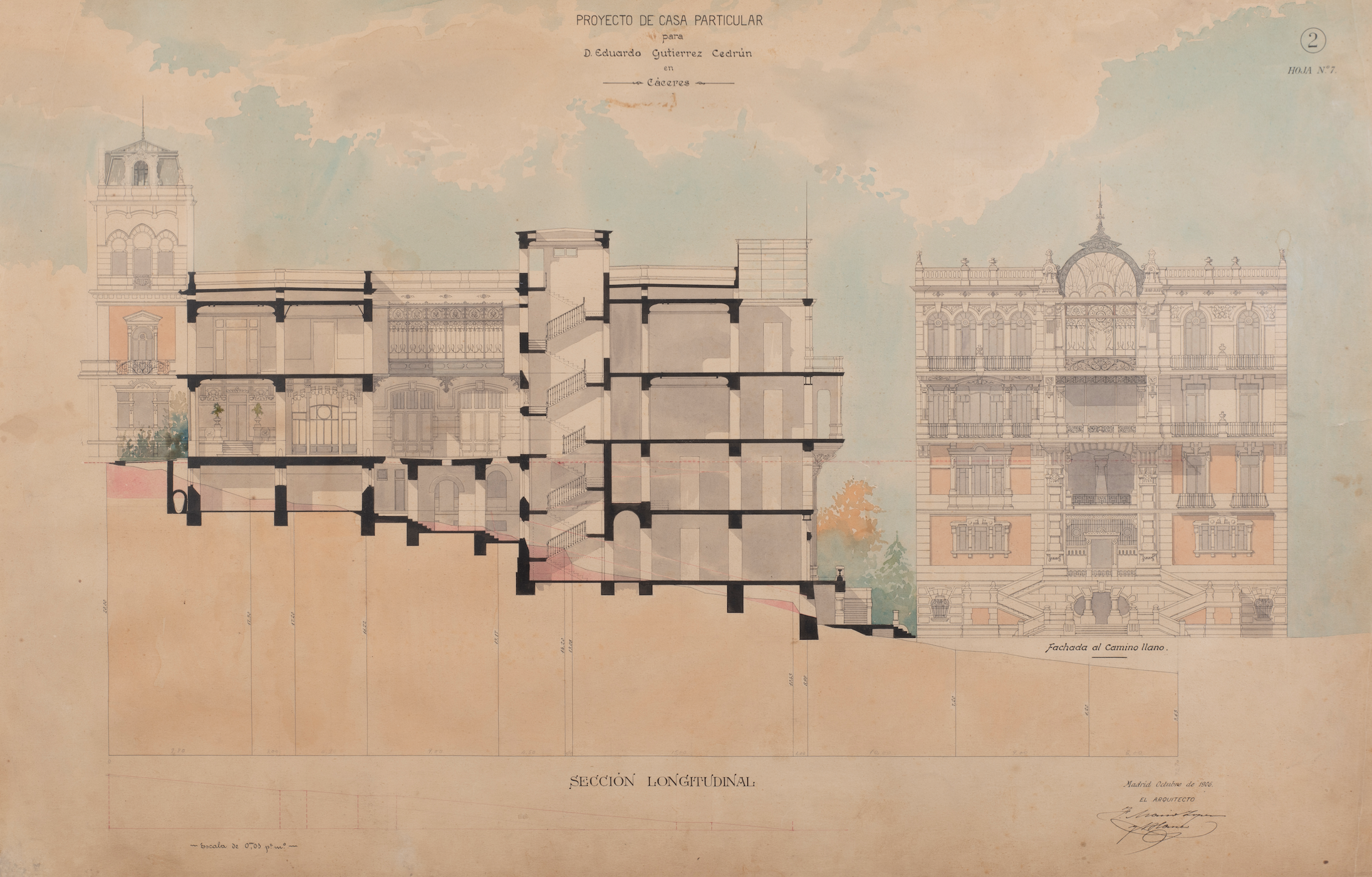

Courtesy of Fundación Valentín de Madariaga.

In Sevilla, the Fondatión Valentin de Madariaga is showing the family’s work in a groundbreaking exhibition. The foundation is dedicated to promoting Spanish arts and culture, with a focus on sustainability, innovation, and social impact. From the early, hand-drawn plans to the present day, environmentally-friendly plans, The López-Izquierdo exhibition is a singular opportunity to see the development of art and architectural needs, developments, and plans, from the 1900s to the present day. Recently we spoke with fifth-generation architect Mariana Vilallonga López-Izquierdo on the occasion of the exhibition.

Your family is being shown together for the first time in an exhibition at the renowned Fondation Valentin de Madariaga. It must be fantastic to see your whole family’s creative genius in one place? What does this mean for the legacy of your family? Will you inspire your son to also study architecture?

I feel very honored to be part of this legacy of architects and artists, hopefully, it will continue into the following generations. We instinctively surround ourselves with creative people, so you see that it’s not just a question of genes – we also seek to share our lives with people of the same mentality. I also strongly feel the responsibility of carrying my last name and keeping the bar high. Hopefully, I’ll inspire my children to be creative and educate them on the sensitivity of seeing beauty in little things. Drawing is a very personal language where you can express yourself when you can’t find words to describe something, an emotion, or a feeling.

How was the creative process during the preparation of the exhibition? Did you work very closely with Valentin de Madariaga?

Valentín gave us total freedom to do what we wanted. More than a creative process, it was a process of collecting the artwork from generations and presenting it in the best way possible. We have to thank Valentín for his generosity and vision, and for inspiring us to exhibit our family legacy in his wonderful foundation.

You form part of a long legacy of architects and creative minds—the fifth generation, to be specific! How does it feel?

It’s an incredible feeling! I wasn’t completely aware of the extent of what my predecessors had accomplished until we collected some of their works to show at the exhibition.

My family asked me to take photos of my great-great grandfather’s existing buildings in Madrid, the ones that had survived the fires after the Civil War and that hadn’t been re-modeled or demolished throughout time.

It was only then that I truly discovered the wonderful work that Felipe Mario López Blanco had constructed in Madrid. Unique places like “La Colonia de la Prensa” (1905), an example of perfect urbanism and landscaped rationalist dwelling that brought Modernism to Madrid.

It was he who launched the first generation of architects in the family. After that, we all followed him: from my great grandfather to my grandfather, my mother, and two aunts, my two siblings, and myself.

Courtesy of Fundación Valentín de Madariaga.

Over the past 200 years, architectural needs, possibilities, and styles have changed vastly. Do you think that it is more difficult to work for today’s generation?

Yes, it absolutely is. Two hundred years ago, there were a lot more opportunities for architects. The Industrial Revolution brought the arrival of new materials such as iron, therefore architects and engineers started to design many buildings from scratch, like railways, bridges, stations, and libraries. There was a lot of work. Nowadays, almost everything has been constructed already, so any architect’s work has become less disruptive. Many of them are based on the existing buildings.

But, thanks to digitalization and cutting-edge technology, we can easily see what’s going on in other parts of the world, as well as draw and model much more efficiently. For context, not too long ago, architectural plans had to be drawn by hand, and also model-making. So, every time there was a mistake you had to start over from scratch.

Now, we have numerous tools at our disposal to draw and make models, from 2d digital drawings to 3d software—to the extent that 3d printers are being used to build constructions.

Do you collaborate on projects within the family? How is the working relationship?

Not at the moment. When I was younger, I used to help my mother, Coro López-Izquierdo, who is an artist, prepare the canvas base and fit paintings on it. One of the latest themes she has been exploring is Street Art, specifically how it is applied to different buildings worldwide.

My father—Mariano Vilallonga, architect and sculptor—and my brother—Mariano J. Vilallonga—also architect and sculptor) have both collaborated with my mother by intervening in her artwork. Sometimes, by drawing over her paintings or by doing a hybrid of painting with sculpture.

Whenever any of us is working on an artistic or architectural project, we share our ideas to receive feedback from the family. When designing, it’s very helpful to be immersed in a creative environment with like-minded people, an atmosphere we enjoy at our country house in Segovia most weekends.

A beautiful place, it also has a big studio where we can experiment as much as we want and need. It’s really a very exciting, creative environment. Imagine the music on, the smell of turpentine and oil, the melted red wax used for modeling sculptures (that are later taken to “the oven” to make them on bronze or any metal), everyone doing their own thing.

For us, it’s natural to work on the weekends. It’s a way of being. Your job becomes your hobby. Being close to nature especially helps in the creative process. Art is therapy, it’s a way to disconnect from the everyday routine. Architecture is sudoku. Both feel good because they stimulate your brain.

Courtesy of Fundación Valentín de Madariaga.

You received scholarships to study in Brazil and California. Where did you end up?

I feel very fortunate to have ended up in both places! First, I studied art and architecture in San Diego, California. A year and a half later I went to Brazil to study architecture at PUC (Pontificia Universidad Católica), in Rio.

I’ve always loved traveling and living abroad, really enjoying the challenge of having to learn a new language, to live in a new place, with new “rules”. The experiences were incredibly enriching.

In Rio, I had the opportunity to work with “RUA Arquitetos”, an architecture studio formed by Pedro Rivera and Pedro Evora. I collaborated with them on the Competition to design the Olympic Golf Clubhouse for the 2016 Olympic Games in Rio de Janeiro. To our surprise, we were the finalists and the pavilion was built.

Having worked in studios not only in Madrid but also in Rio and Paris, what were the main differences and similarities in their approach to architecture, urban planning, and interior design?

It’s very interesting to see how architecture changes from one city to another. Of course, climate and lifestyle affect the design of a building. For example, in Rio de Janeiro, due to their high temperatures, buildings tend to be more “open” in order to create cross ventilation. The spaces “flow” more, architecture is simple, flexible, and fresh. This vibes well with Brazilian culture. Think of Brazilian architect Oscar Niemeyer, whose source of inspiration were the curves found on Brazilian mountains, their rivers, Brazilian women…

Paris, in contrast, is a very formal city in terms of its architecture. There is a lot of regulation and bureaucracy, everything is difficult, however, what is amazing about Paris is how it has stayed the same throughout recent history. In part, we have to thank the numerous urban and architectural regulations which respect Haussmann’s renovation plan of Paris in the 19th-century.

When I arrived in Paris, I had to climb the five floors, carrying my luggage because there was no elevator. This is very common in Paris. Old buildings were constructed for a different, perhaps slower, life. They aren’t really compatible with today’s fast-paced lifestyle.

In Madrid, architecture is much more technical. Whereas in other countries architecture firms care more about having good design skills, Spanish studios demand more construction and structural knowledge.

Your aunt Alicia López-Izquierdo is focusing on biostructures, which is a very current topic. How do you think this will change the urban landscape?

Biostructures, off-grid buildings, sustainable and self-sufficient buildings…the urban landscape is changing rapidly.

With climate change, we are more and more conscious that we have to live in a sustainable way. In architecture, we practice this idea by applying “green” concepts when designing a building, for minimal environmental impact (respecting heights, the use of local materials, etc.), having cross-ventilation, a good building orientation (it helps to generate solar heat gain), solar panels to make electricity, the re-use of rainwater, a geothermal system for heating and cooling, to name a few.

Courtesy of Fundación Valentín de Madariaga.

If you could have dinner with any 3 artists or architects, living or dead, who would you choose?

Leonardo da Vinci, because he was an actual genius, capable of all disciplines (art, architecture, engineering). He was a visionary of his time.

The architect and designer Charlotte Perriand. She is an example of a talented and inspiring woman that was respected in a world dominated by men.

It would be incredible to have a dinner with my 3 predecessors at the same time: my great-great grandfather Felipe Mario López, my great grandfather Enrique López-Izquierdo and my grandfather Enrique López-Izquierdo Camino. This way, they could explain to me their vision of architecture throughout time.

“López Izquierdo: Five Generations of Architects” is on view through June 27, 2021.