A wall of “rejects” greets visitors at Marlene Dumas’s splendid Tate Modern retrospective. Dozens of anonymous faces, painted in fluid black ink, stare back as you come in. Their eyes, occasionally cut out to reveals other painted eyes underneath, burn with an unsettling intensity. Of these individuals, we’ll know nothing more. At some point, their features spoke to Dumas enough for her to reach for a brush. That’s all. The rest of the story has been tossed out. As it turns out, these pictures themselves have been tossed out. These are the ones which didn’t make the cut for the artist’s “Models” series (1994). Rejected, they stand together as a concentrate of humanity: anonymous and multifarious. As mysterious as a crowd.

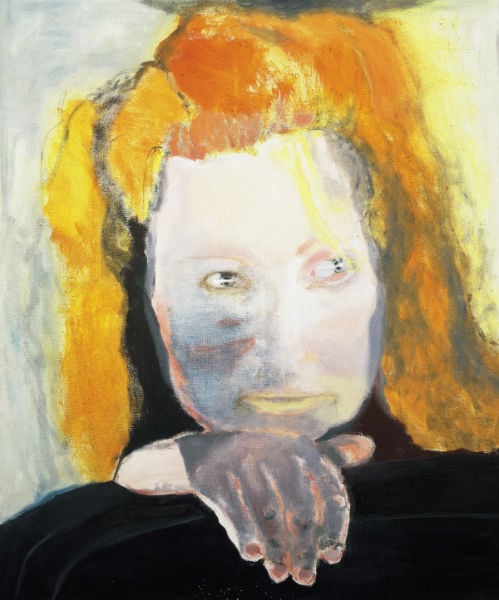

“Rejects” (1994-ongoing) is an apt introduction to Dumas’ practice. The South African painter, who relocated to Amsterdam in 1976, has secured her place at the forefront of contemporary painting for her uncompromising approach to the body and incisive portraiture. Yet, what’s striking here is how incidental the subject often appears, in short, how un-portrait-like her portraits really are. Her depiction of Osama bin Laden (Osama, 2010) has less to do with the al-Qaeda leader as it has with the way his image has been transformed into an icon of evil itself by ‘War on Terror’ rhetoric. Dumas doesn’t really look at the man but captures the accretions of meaning that have become attached to the picture of his face. In the series of portraits from the 1980s that first put her on the map, Dumas often forgoes her subjects’ names: like in the striking Genetic Longing (1984), in which a long-haired woman is rendered in fauvist ochres and greens. A self-portrait of the period, Evil is Banal (1984), nods to Hannah Arendt’s controversial reading of Nazism. “It could have been me,” Dumas seems to say, looking away from the canvas, her face marred by a black mark as if she had been stepped on. “It could have been you.”

Marlene Dumas, Glorious Venice (1995)

Photo: © Marlene Dumas

Perhaps inevitably for an artist who grew under apartheid in a rural, Afrikaans family, Dumas’s art is tainted with politics. One might even venture that the self-imposed darkness of most of her palette is semantically charged. But it’s never moralizing. Dumas is no banner-bearing activist. Her commitment can be found in the making of her images themselves, which are, more often than not, responses to other images, be they mass media pictures or family snapshots. Formally redolent of Rejects, the Black Drawings (1991-92) picture the faces of black men whose bodies had once been photographed by colonial anthropologists. Sliding the lens upwards, Dumas responds to the pseudo-scientific record with a portrait, one which injects a sense of personality into these serially-objectified black male figures. A few years later, she painted a photograph of her sleeping infant daughter twice: once with a fair skin, Cupid (1994), and once with a dark skin, Reinhardt’s Daughter (1994), teasing, like the eponymous American abstract painter before her, the impact a different shade of black can trigger.

Yet, it’s in her depiction of the female body that Dumas is the most convincing. Her portrayal of Amsterdam prostitutes is at once tender and unabashedly erotic, compassionate and empowering. In the “Magdalenas” series, executed for Dutch pavilion at the 1995 Venice Biennale, she stages statuesque women on tall canvases as so many goddesses. Among a mishmash of references—early images of supermodel Naomi Campbell, the biblical redeemed temptress, Botticelli’s Birth of Venus—they appear like a set of caryatids, each supporting a different form of femininity, and each with their own color, shape, and age. Dumas conjures up new archetypes to combat those that 5 generations of feminism are yet to debunk. Instead of limiting the field of possibilities, her Magdalenas champion multiplicity as the norm.

Marlene Dumas, The Widow (2013)

Photo: © Marlene Dumas