Some 50 years ago, Stephen Somerstein, who was the editor of the evening newspaper of the City College of New York, took a bus from New York to the South, intent on photographing Martin Luther King Jr.’s voting rights march from Selma, Alabama, to the state capital of Montgomery. As the country looks back on that historic event, now immortalized in the film Selma (which has garnered an Oscar nomination), those images are being featured in the New-York Historical Society exhibition “Freedom Journey 1965: Photographs of the Selma to Montgomery March by Stephen Somerstein.”

Today, Somerstein would probably be armed with a compact digital SLR and a smart phone. Back in 1965, the 24-year-old photographer brought no less than five separate cameras to do the job, and a sturdy backpack for carrying them. He managed that equipment, which included multiple instruments slung across his body and spare film at the ready, unassisted.

While today’s photographers are often limited only by the size of their memory card, Somerstein had only 10 rolls of him with him, enough to shoot a mere 400 frames—and he couldn’t review his work until he was back in the dark room days later. It was all the film he could round up before the trip, which was taken on extremely short notice. “Every frame that I took had to be a perfect shot,” Somerstein recalled at a recent press preview at the Historical Society.

Stephen Somerstein speaks about one of his photos of the Selma-Montgomery voting march rights at a press preview of his exhibition at the New-York Historical Society.

Photo: Sarah Cascone.

Although Somerstein certainly recognized that the march was important, he decided to attend mainly because several civil rights groups from City College were making the trip. “We had to cover our own students who were going down there to lay their bodies on the line,” he explained. “I had no idea how extensive, how remarkable it was going to be.”

To keep from being overwhelmed by the importance of the occasion, Somerstein focused on the task at hand: documenting the event in film, making instantaneous technical decisions. “I had to concentrate on the photograph and not be bedazzled by the moment, because you won’t get the photograph—you’ll feel great, but you won’t get the photograph!”

On March 24, Somerstein and his classmates joined the march at its final campsite at St. Jude, a Catholic high school that finally closed its doors last May. He attributes some of the success of his photographs to the lighting conditions: after rain the night before, an overcast sky created the conditions for even and consistent lighting, making it possible for Somerstein to shoot without having to constantly readjust his camera settings to account for bright sun or dark shadows.

In 2015, the Internet affords photographers the ability to widely disseminate their work almost instantly. It’s easy to imagine similar pictures taken today becoming viral sensations. At the time, however, the images went largely unnoticed, save for one of Joan Baez, which was featured in a double-page spread introducing a 1966 Joan Didion–penned New York Times article on the folk singer’s commitment to nonviolence.

Of course, as Somerstein was quick to point out, most images aren’t iconic right away. An image can be technically proficient and beautifully composed, but that doesn’t mean it’s more than a nice photograph. He recognizes that his photographs have taken on “far more luster and complexity with time,” assuming a power and impact that only comes as the historical significance of the events they depict becomes fully understood. As such, one can only imagine how photos of protests in Ferguson and Hong Kong will be perceived half a century from now (see Missouri Museum to Preserve Ferguson Protest Art and Is Hong Kong’s Protest Art Worth Saving?).

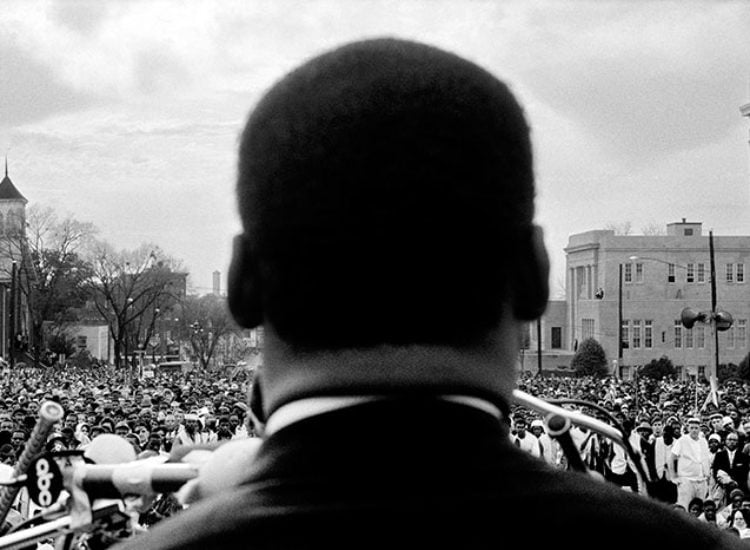

Stephen Somerstein, Spectators in Montgomery.

Photo: Stephen Somerstein.

After graduation, Somerstein went on to enjoy a successful career as a physicist. It wasn’t until many years later that his work was publicly exhibited, and the powerful scenes from Montgomery were widely seen. Now, his images have helped inspire an Oscar-nominated movie—the Selma poster, a shot of the back of King’s head taken in front of a crowd, is based on one of Somerstein’s photos, and it isn’t a coincidence. Somerstein gave the filmmakers access to his photographs, and has an agreement worked out for their restaging in the movie. While he hasn’t seen Selma yet, Somerstein has caught the trailer, of which he remarked, “I do see the influence of my photos in it.”

“Freedom Journey 1965: Photographs of the Selma to Montgomery March by Stephen Somerstein” is on view at the New-York Historical Society through April 19.