Masatoshi Izumi, the artist best known as one of Isamu Noguchi’s most trusted collaborators, died this past September. A cursory Google search elucidates how little known Izumi was in the Western art world, and how under recognized by its art media, which wrote about him only a handful of times, and mostly in the capacity of helper to Noguchi, the esteemed 20th- century Japanese-American artist and architect whose biomorphic forms reimagined how sculpture could interact with its environment.

Those articles tend to describe Izumi in his own right as a stonecutter from a long familial tradition of stonemasons in Mure, a small, hilly town near Takamatsu, on Japan’s Shikoku Island, where he was born in 1938. But few mention the artistry with which Izumi regarded stone, and how that vision inspired Noguchi to work with the material more technically.

In 1964 Izumi, then 25, opened the Stone Atelier, a stone-carving workshop specifically designed for artistic and architectural projects. The workshop presented a new perspective to the community by positing stone as something of more value than its utilitarian use as a building material for more ubiquitous forms of output, such as tombstones and lanterns. It was for this reason that the governor of the Kagawa prefecture, a local architect himself, sought to introduce Izumi to Noguchi, who at the time was visiting from Italy, where he was working on a series of sculptures carved from Tuscan marble. The meeting sparked a revelation for Noguchi, who, in 1966, reportedly told Izumi he liked him because he “hadn’t gone to art school, didn’t speak English, and loved stone.”

Noguchi propositioned him: “Let’s study stone together.”

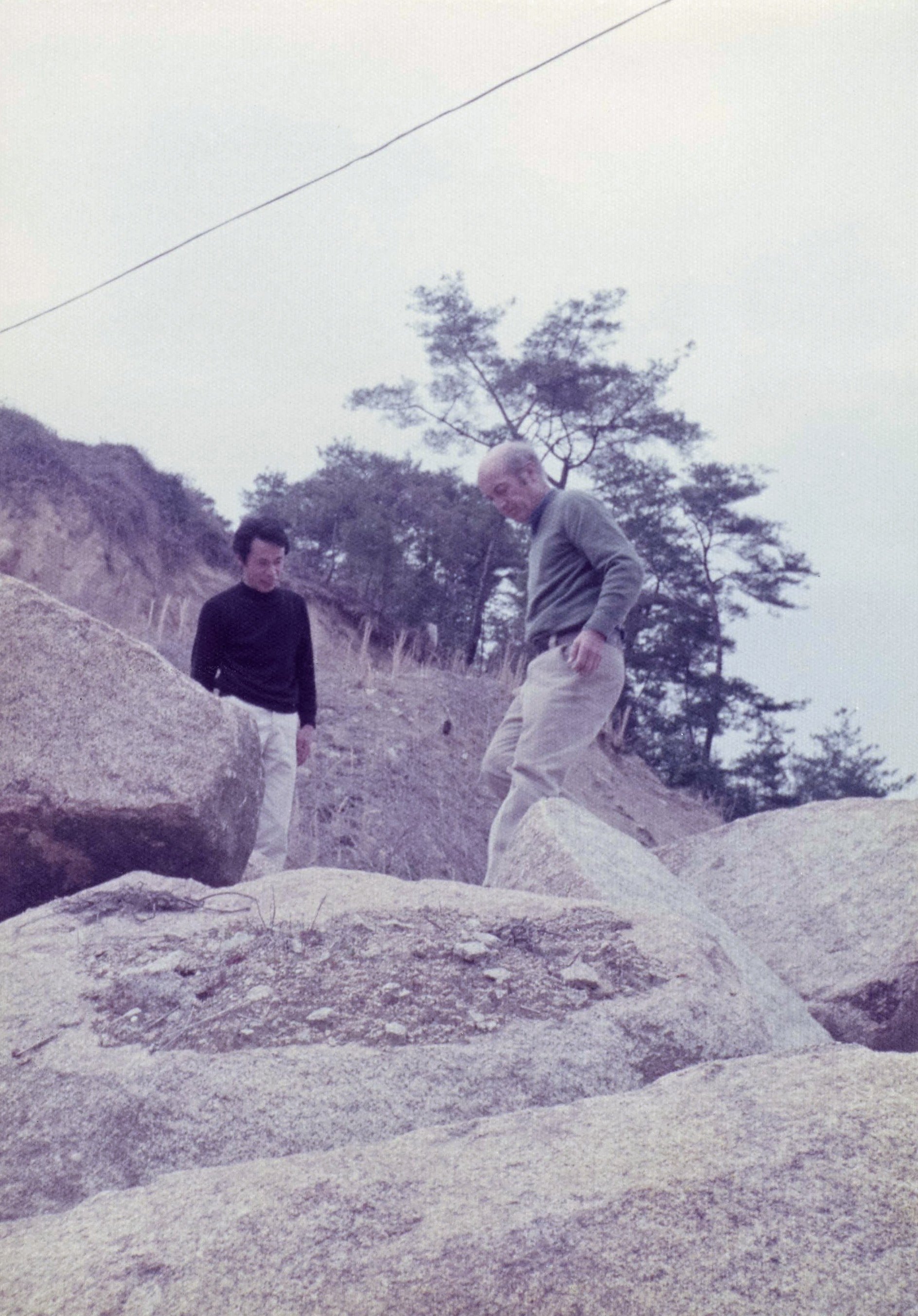

Noguchi and Izumi with Black Sun in Seattle in 1969. Photo courtesy the Noguchi Museum Archive.

And so they did—for 20 years. They collaborated first to produce the behemoth ring-shaped sculpture Black Sun (1969), one of Noguchi’s most recognized works, cut from a single piece of Brazilian granite that originally weighed 30 tons. With help from Izumi—who had learned from his father and grandfather how to properly whittle down stone, in this case to just 12 tons—they realized the nine-foot-tall polished black ring, with its multifaceted obtrusions, that Noguchi envisioned as a meeting place for young people in Seattle’s Volunteer Park.

Because Izumi’s Mure-based house was too small to host Noguchi—who was prone to collapsing from exhaustion and frustration after long days of carving stone—Izumi reconstructed a 200-year-old Edo-period merchant’s house on his land, complete with a circular wall to enclose an outdoor studio featuring a kura, a traditional barn-style workshop, and a terraced outdoor sculpture garden, which, embedded into the hillside, offered Noguchi a place to display his works and experiment further with site-specific sculpture. Over time, the house became known among locals as Isamu-ya, or “Noguchi’s house.” After its completion, Izumi planned a similar property for himself, but made of stone, instead of the wood of the merchant’s house. In the center of the structure, he placed the columnar cutout from the hole in Black Sun.

Over the years, Izumi would teach the American-born artist about every stage of stone-cutting that he had learned as a boy—traditions which in some way called into the void of connection Noguchi felt toward much of Japanese culture, which he felt generally rejected by because of his mostly absent and indifferent father, the itinerant Japanese poet Yone Noguchi. Izumi went with Noguchi on stone-hunting trips, showing him how to “choose a good one,” according to Fumi Ikeda, administrative director of the Isamu Noguchi Foundation of Japan, as well as how to split and move mammoth boulders, and how to install works using the hardest stones, like basalt and Aji granite.

According to the Noguchi Museum, Izumi would also occasionally procure regional stones that he thought Noguchi would find useful for his projects. From 1967 until Noguchi’s death, in 1988, Izumi worked alongside the artist to create works including Supreme Court Building Fountains, Energy Void, Time and Space, Tokobashira and Tengoku, Landscape of Time, Momo Taro, The Spirit of the Lima Bean, Constellation, Water Garden, and others.

Izumi with Black Sun in Japan in 1969. Photo courtesy the Noguchi Museum Archive.

Close as Noguchi and Izumi were, tensions still scored their collaboration at times. “I’m not sure their relationship can be summed up in the word ‘friendship,’” says Ikeda, while Brett Littman, director of the Noguchi Museum in New York, notes that Noguchi was “a tough collaborator.”

“When things went wrong, Izumi was the first one to blame,” Littman said. Much of the time, it was their fundamental, cultural differences in how they approached stone that informed their divergent points of view on whether or not a project was successful. “Whereas Noguchi worked with stone as a medium that he could freely shape,” Ikeda says, “Izumi looked for the spirit within the stone. He revered it and sought ways to minimize the harm he caused it.”

But Izumi, who Littman describes as possessing “a tremendous amount of patience,” also recognized that their discord fueled their collaboration and productivity. “About their relationship, Izumi often said, ‘We each had something that the other lacked,’” Ikeda recalls. “Noguchi-sensei could draw out a power we never imagined.” Izumi would also often tell Ikeda that he and Noguchi “could work well together because we were both poor.”

Izumi oversaw the completion of a number of Noguchi’s unfinished works after his death in 1988, including Black Slide Mantra in Sapporo while also fulfilling Noguchi’s wish that his studio space—the Isamu Noguchi Garden Museum Japan—be maintained as a museum to inspire young creatives. He also assumed the role of president of the Isamu Noguchi Foundation of Japan, which he continued until his death this fall.

Izumi and Noguchi in 1987. Photo by Jun Miki and courtesy the Noguchi Museum Archive.

As an artist in his own right, Izumi did not pursue his own career until 1995—when he, at 60, opened his first solo exhibition at the San Francisco-based Japonesque Gallery. His works today live in private collections, gardens, and museums including in the Art Institute of Chicago, the Asian Art Museum of San Francisco, and the National Palace Museum of Taiwan. His work, which Littman notes was often dismissed by much of the art world as being too similar to Noguchi’s, explore themes around stone’s relationship to water, around materiality in general, and the idea that everything, eventually, returns to the earth. They adhere more to the stone’s natural form, featuring carefully carved rivulets and pockets so as not to disrupt its character from within, as with Night Rain II (2016), a 4,000-pound block of Swedish rosso vanga granite and Owan—Tsukubai NY-01 (2008), sculpted from a nearly 5,000-pound hunk of Japanese Tonoku basalt.

“The thing is, Izumi leaks into Noguchi’s work too,” Littman said. “It’s a two-way street. Many people have, to be frank, dismissed his work as being too derivative of Noguchi’s. But in truth, it was, in many ways, a dialogue.”